The Business of Baby: Podcast Interview with Jennifer Margulis and Book Excerpt

In this Kindred Fireside Chat, Jennifer Margulis talks with Lisa Reagan about the book that took her ten years to write. The Business of Baby covers the complex gauntlet of decisions faced by new parents in the first year of their children’s lives and shows how American families are trapped in “institutional failure” and systems that do not support wellness. Margulis, an award-winning writer and professor of investigative journalism at Brandeis University, illustrates clearly why American children consistently land at the bottom of all international measures of wellness. Margulis’ brave and insightful investigation is a welcome guide for “parents questioning a business model of care whose performance record for children and profits is crystal clear.”

The Business of Baby covers the complex gauntlet of decisions faced by new parents in the first year of their children’s lives and shows how American families are trapped in “institutional failure” and systems that do not and cannot support wellness. Margulis, an award-winning writer and professor of investigative journalism at Brandeis University, illustrates clearly why American children consistently land at the bottom of all international measures of wellness. Margulis’ brave and insightful investigation is a welcome guide for parents questioning a business model of care whose performance record for children is failing and fundamentally incapable of producing wellness.

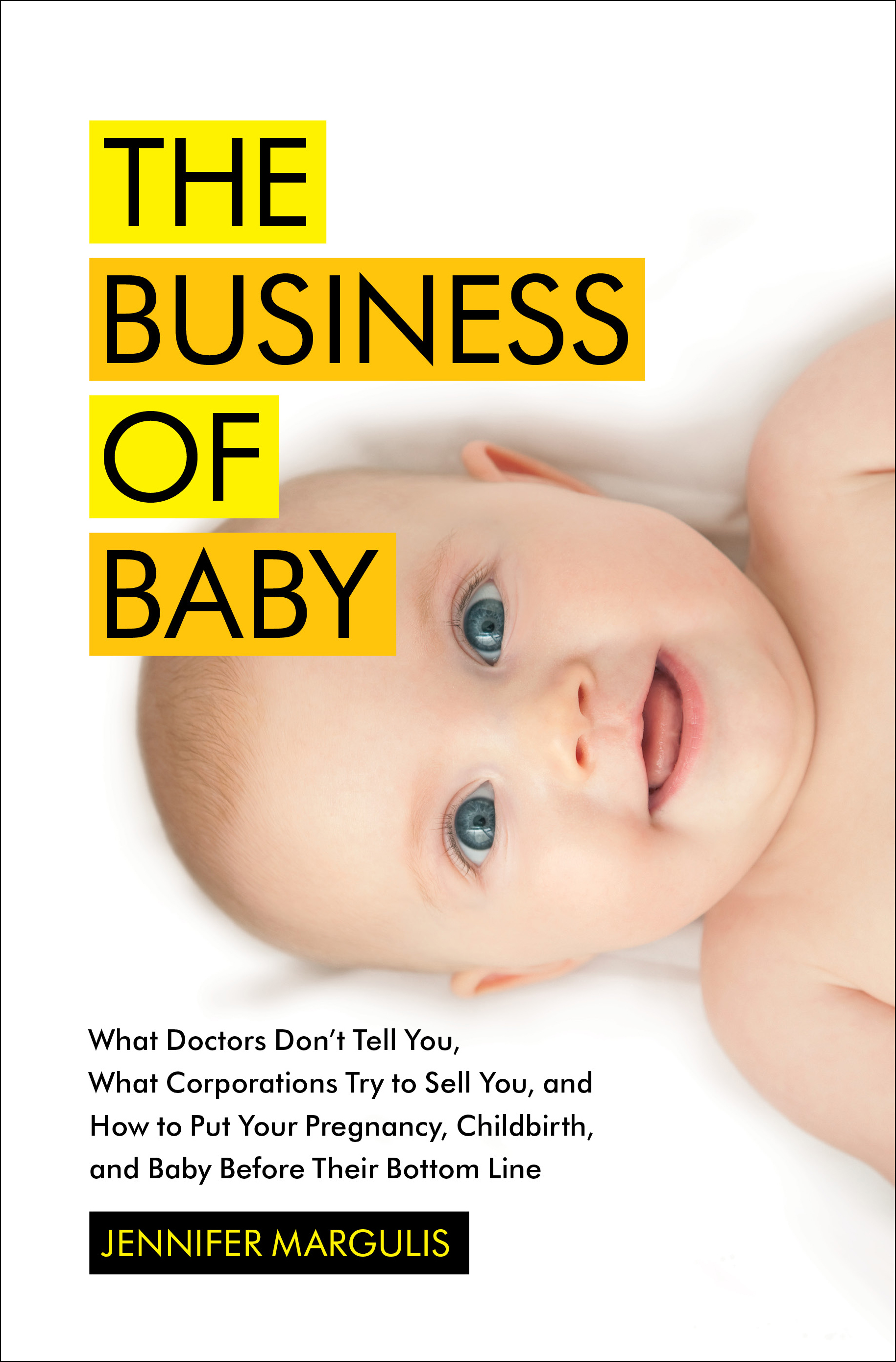

The Business of Baby: What Doctors Don’t Tell You, What Corporations Try to Sell You, and How to Put Your Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Baby BEFORE Their Bottom Line

Excerpt adapted by Jennifer Margulis, Ph.D., for Kindred

When I took my oldest daughter to her six-month well-baby visit at a big pediatric practice on Peachtree Boulevard in Atlanta, the doctors were running behind.

At first the baby stood on my lap, holding my hands and bouncing up and down, smiling at the other patients. But as it got closer to naptime, she started to fuss.

As the minutes ticked by, her whines became more strident. I walked her around, even taking her outside to look at the cloudless sky. Nothing worked. Used to napping in her crib, Hesperus started to sob from fatigue. When it was finally our turn to be seen, I was also close to tears.

“What’s wrong with the baby today, Mom?” the thirty-something pediatrician asked, genuinely concerned.

I explained we had waited for almost an hour and Hesperus was long overdue for a nap. The doctor clicked the light on her otoscope, a handheld device the width of a thick marker with a funnel on the end, to peer into the baby’s ears.

“I think Miss Hesperus has an ear infection!” she announced, clicking the light off with her thumb and rolling her chair to the counter to scribble a prescription.

My face felt numb.

Hesperus had never needed medication—or been sick—before this visit.

“Has she been tugging on her ears?” the pediatrician asked.

“Not that I’ve noticed,” I admitted.

“I’ve prescribed an antibiotic,” the doctor handed me a scrip, “and here are some free drops . . . for the pain.”

I filled the prescription at the practice’s pharmacy, which entailed another twenty minutes of waiting, paid the copay for the visit and the additional copay for the medication. But I waited to give my daughter the antibiotic.

After a much-needed nap, the baby was her happy self again. I found out later that if our pediatrician had waited twenty minutes and looked in her ears again when Hesperus was calm, she would not have seen any sign of infection.

Why? Because my daughter did not have an ear infection.

Middle ear (otitis media) infections are more difficult to diagnose correctly than you might expect. When the doctor looked into my daughter’s ear with the light on the end of the otoscope, she was looking at the eardrum. Behind the eardrum is the middle ear. The doctor made the diagnosis of an infection based on observing the eardrum. Normally the eardrum is white, a semitranslucent membrane covering what looks like a tiny arm. This is actually a bone (the malleus or hammer), which picks up sound vibrations. An eardrum may be red or pink because of an infection. Hesperus’s eardrums looked bright red.

But an eardrum may be red or pink for another reason. In this case Hesperus’s eardrum was red because she’d been crying.

Since the pediatrician was already running forty-five minutes behind, she needed to get us out of the office as quickly as possible. Pediatricians, like everybody else, want to please their patients. Our pediatrician was delighted to solve a problem, even though the problem she diagnosed didn’t actually exist.

In the United States ear infections are one of the most overdiagnosed and overtreated infections among American children, who collectively receive more than thirty million courses of antibiotics for ear infections each year.

The only problem with the baby was one the doctor’s office had caused.

Midwife and Right Livelihood Awardee, Ina May Gaskin, calls The Business of Baby: What Doctors Don’t Tell You, What Corporations Try to Sell You, and How to Put Your Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Baby BEFORE Their Bottom Line, “A searing and well-researched exposé” and “a must-read for expectant mothers.” But one New York Times reviewer calls the book “shockingly irresponsible.” Read the book to decide for yourself who’s right.