Deeply horrified by the American medical model’s treatment of pregnant women and babies when she arrived in the United States in the 80s, British-trained midwife Jennie Joseph successfully worked to create an evidence-based model of prenatal care for women, especially women of color who are three to five times more likely to die in childbirth in the US than white mothers. Her pioneering work includes providing human connection and empowering education, while also training mothers, fathers and extended family members to identify and arrest the cascade of interventions inside the hospital birth system that lead to complications and death.

Jennie Joseph’s interview with Kindred comes as the first annual Black Maternal Health Week launches from April 11-17, 2018, and March for Moms on Washington, DC, on May 6, 2018, prepares to demand the implementation of missing public policies and social safety nets to support mothers and babies found in most developed countries. As Jennie says in the interview, the only way forward now is grassroots movements of individuals and organizations acting collaboratively and intentionally as a consciousness-raising movement to save ourselves from an unyielding, capitalist and deadly medical system.

Read the transcript for this interview below.

Find Jennie Joseph at www.jenniejoseph.com

Find more information about the March for Moms at www.improvingbirth.org

Find more resources and information on Black Maternal Health Week at www.blackmamasmatter.org.

Sections in the Interview Transcript Below

Saving Ourselves from a Capitalist Medical System

Saving Ourselves: What Does Empowerment Look Like?

Insights from Intentionally Serving High-Risk Mothers

Change Is Coming: From the Grassroots Up

Preparing for Both Progressive Change and Predictable Backlash

Midwife Jennie Joseph: Saving Ourselves from a Capitalist Medical System

AN EDITED TRANSCRIPT OF THE ABOVE INTERVIEW

LISA REAGAN: Welcome to Kindred, an alternative media and non-profit initiative of Kindred World. This is Lisa Reagan and today, I am very excited to be talking with Jennie Joseph on the eve of the first annual black women’s maternal health week, which is going to be held from April 11-17 and the March for Moms in Washington DC and around the country on March 6. Jennie is a British trained midwife and the founder and executive director of Commonsense Childbirth. She is the creator of the JJ Way, whose evidence-based approach has resulted in marked improvement. I cannot even say that emphatically enough in birth outcomes for women in Central Florida. So, welcome Jennie.

LISA REAGAN: We have a lot of territory to cover, but…

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes.

LISA REAGAN: I just want to start with what’s going on right now because there seems to be an uptick in interest and notice and coverage of this issue. I think it was last month, I just about veered off the road when I heard your voice come over an NPR radio show. I was like, what, what? I always have that fantasy land thought in my head like I did back when Jamie Grumet was on the cover of Time Magazine nursing her four year-ld child. I though then, “Okay, we can all go to bed. We have made it now as activists.”

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yeah.

LISA REAGAN: It is very exciting.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes it is. They do have the coverage, particularly on the topics that I am very concerned about and also at the same time, it is bittersweet. It’s been a long time coming. This is not new. This is not a crisis. This has been ongoing really in this country for a very long time, talking about the poor outcomes for black women specifically, Native American women, and women of color in the United States when it comes to maternal health, their morbidity and their mortality and, you know, there has been a lot of coverage as you’ve said, even some celebrity involvement. Recently talked about Serena William’s birth and her birth outcome and so it has come to a head and almost hit critical mass I would say. Those of us in the trenches and those of us that have been aware know about this. This has been ongoingly the case. This is not new.

LISA REAGAN: That is true and just to catch our listeners up in case your not familiar with the statistics, let me just rattle off a couple here:

According to the CDC, black mothers in the US die at 3-4 times the rate as white mothers, one of the widest of all racial disparities in women’s health and put another way, a black woman is 22% more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, 71% more likely to perish from cervical cancer, but 243% more likely to die from pregnancy-related, childbirth-related causes. In a national study of 5 medical complications that are common causes of maternal death and injury, black women were 2-3 more times likely to die than white women who had the same conditions.

So this is the framework, the background, the issue that is being addressed with the march, with the new Black Maternal Health Week. It is coming up and a lot of the features that are making it into even mainstream news right now.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yeah.

LISA REAGAN: So I want to say, the first time I listened to present about the JJ Way (read an analysis report of the JJ Way here), I was listening to a lecture that you were giving to professionals and I was listening closely because I was trying to hear: what is it she’s doing, what is it she’s doing, what is the magic, the secret? What is it? What is it? Of course, we are all there with our complicated intellects looking for the complicated part that we could pick up and package and resell and put out and get out quickly in a distribution model; but when you started describing the human connection that is happening and this is it, this is the big secret. I cried. My heart just broke. I, like everybody else, asked: how do you reproduce that and quickly and get it out there? But I think you are, as much as one woman is capable of doing that. Can you address that?

JENNIE JOSEPH: I certainly can address it. You know, I am not the only one doing it. There are many others in whichever discipline or medical field that we’re in that has figured out ways to do this. There is quite a big movement called patient-centered care that has been for a good few years a topic of discussion and subjects of learning at conferences and articles have been written and even tool kits are in existence for how do you do patient-centered care.

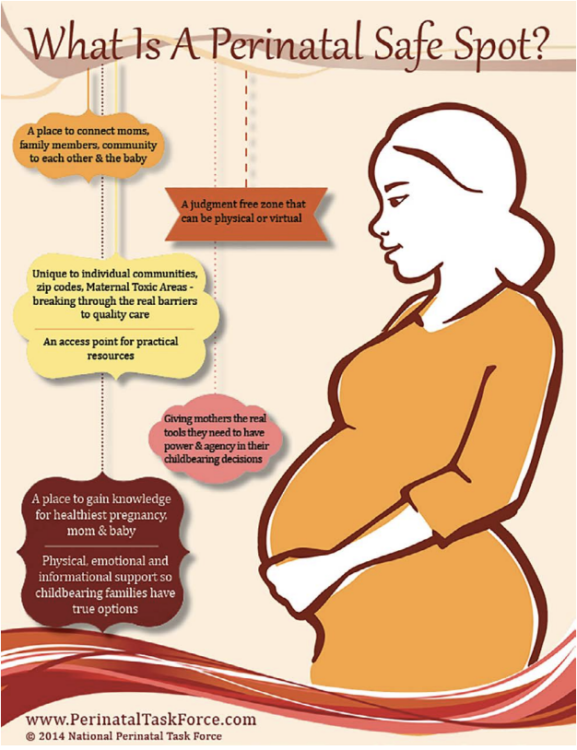

As a midwife, I would suggest that most midwives who are practicing the Midwifery Model of Care do a very close, if not the exact same thing that I do as far as providing literally women-centered, family-centered, safe, cultural humility inside of their care, etc. The JJ Way model, I named it that just as coming up with a quick acronym one day, but the model itself is an extended Midwifery Model of Care, but it has four basic tenants and they are very very simple. The number one cornerstone of this model is access. It is access not only to perhaps a physical building, a practice, or an office or physician or midwife office, but it also access to having somebody to hear you, access to having medical care, to receive the care, access to information that is going to valuable that could actually save your life. Access to anything, you name it, access, number one.

Followed quickly by connection. Once you can connect, a woman to have baby, to her situation, to your staff, to yourself, once she feels safe to connect, a whole world opens up.

You can now educate. You can support. At the ultimate end, she will be empowered. The four cornerstones of the JJ Way are access, connections, knowledge and empowerment. One has to come before the other. You cannot do it out of order. You can’t do it in a silo. You can’t do it if your heart isn’t right. It is all about your will to provide a certain level, a certain quality of care, whether it is midwifery care or cardiology, it doesn’t really matter. What it’s about is can you stand with this person who is in front of you, in a genuine and open way such that her best interest becomes yours. That’s the JJ Way.

LISA REAGAN: So this has a lot to do with the practitioner who is practicing inside of an existing medical model.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes, it is because the model that we have is broken. It doesn’t matter which was you look at it, whether it starts at the, you know, the office level, the community-based provider or it goes all the way to big behemoth hospital system.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes, it is because the model that we have is broken. It doesn’t matter which was you look at it, whether it starts at the, you know, the office level, the community-based provider or it goes all the way to big behemoth hospital system.

It doesn’t really matter where along that continuum you are, but it is the system itself that is broken. It is the system that says it is okay to create and deliver care this way. It is okay to maintain the institutionalized racism, the institutionalized classism, the institutionalized sexism that is inherent in this system. It is a capitalist system, it is a business model. So everything else falls under that and comes from that approach.

So, yes, on an individual level, we providers can mitigate some of these ills, some of these poor outcomes, some of these egregious harms that we do to women, especially in pregnancy and birth. But, on the other hand, the systems allow us to continue to practice and deliver care the way we do and we are caught up in; even if we wanted to change on a personal level, it’s hard to go against the system.

I can give you an example, labor and delivery nurses, God bless them, are in such dire straights because they have to tow the party line if they want to keep their job and the system has set them up to be the guardian of basically every laboring mother in the United States without really being empowered to do that work. The physician’s are waiting in the wings to swoop in and save the day without the behest of the nurses. The nurses in turn have only to follow the orders that they give them, usually at a distance remotely, and yet, they’re also going to be made responsible when things don’t go well; so the only way that you can manage that kind of craziness is to create structures that keep everybody tied down, literally sometimes, into the systems of care and systems and ways of being.

The entire obstetric model is based on the delivery of the baby. That’s when you bill. That’s when you collect. That’s when the hero measures are in place. But in actuality, as we all know, the perinatal period is before pregnancy, during pregnancy, postpartum and inter-conceptional. All of the energy, all the money, all the efforts, all the talking, all the protocols, headed straight to the delivery room. That one day in this entire spectrum of events.

We’ve got a really rotten, upside down system and so those of us who want to work inside of that or try to work inside of that to fix or make it better have a very long and hard journey, but one thing I think it is time to do, one thing I think that is really imperative that we do, that is take responsibility for what it is. It is time to stop blaming these women, their mothers, their families, their communities, stop talking about them as if they created their own physiology to cause harm to themselves and stop washing our hands and throwing our hands up when it comes to making some significant and drastically needed changes to break this broken system right now and get something else up that is going to be considered quality care for maternity care in the United States.

How the American Capitalist Medical Model is Killing Mothers and Babies

LISA REAGAN: I think the fact that you came into America from a different model and that you had experience in a different model and you knew something else was possible is what it makes it possible for you to even see this the way you’re seeing it because the rest of us have just been enculturated in patriarchy and authoritarianism in the US and we were spoon-fed it from the beginning, from day one, so it is very hard to imagine what else is there? So can you speak a little, about your coming to America experience?

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yeah, I certainly was shocked when I got here that midwifery wasn’t normal or expected or even known about. I came in the late 80s and there were people, at least in Florida, I came into central Florida and I’m still in central Florida all these years later. But there were people that when I landed and talked about my midwifery, you know, background, they were like, “What are you talking about? We don’t do that. Oh yeah yeah yeah, I think back in the day, we did that, but oh no, not now.”

So, I have been here a long time and things have changed and they are certainly a lot more interested in midwives and midwifery. This is not the midwifery that I left in England, that I left in Europe. The midwifery that I am accustomed to is midwifery inside of the Universal Healthcare System where everybody has access to care because it is a human right and where the government creates provision for somebody, some entities and some providers to take care of you through that experience, not just maternity care, that’s throughout all healthcare experiences, but the maternity care is taken care of by midwives who run units, hospitals, practices, outside offices, community-based clinics.

The OB physician is a partner to the midwifery practices, in that where there is a complicated case, then the physician is involved and at the request of the midwife, the midwife refers the patient to the obstetrician for further more extensive care than she can provide. So if you think about it, we’ve got a completely different approach, in that the Europeans and the rest of the world have maybe 80% of birthing women using midwives for prenatal care, postpartum care, delivery, etc and 10-20% of the higher risk women needing obstetricians.

The American model is absolutely the complete opposite, 90% of births are taken care of by obstetricians. And if you think about it, obstetrics is a specialty, just like cardiology is a specialty. A family practice can take care of your sniffles and your sore throat, you don’t need a cardiologist. Similarly, the maternity care is not taken care of by people who were best set to take care of it, midwifery, midwives, right? It is taken care of by obstetricians whose skills far surpass what is needed for the course of a normal pregnancy. So, the difference in terms of who provides the care is vast, but it is not just that, it is the understanding that healthcare is normal, access to healthcare is paramount and that there isn’t going to be anything to impede you getting to have the opportunity for that care and support.

Here, we have another way. Oh, you need to be able to afford to have made provision, to have planned, to be employed, so you have insurance. All of these constraints on a socioeconomic levels are in play, followed by if you don’t have a certain type of insurance. So, let’s say, for example, you’re insured through Medicaid, then you must be relegated to a different level of care, if you have access at all, and then lastly, if you are a certain race, which is where the racism plays in and it has been important that we don’t not talk about that piece. It’s not just sexism. It’s racism that is killing people. It’s not just power over there pocketbook, it’s the power over who they are and it’s important that we acknowledge that truth so that we can be clear about what we’re talking about.

So, the European model, or the Australian model, or wherever you are in the rest of the world where everybody else uses the midwife for the first step, is for the primary healthcare of pregnant women and maternity care. This is normal around the rest of the entire world. Even in areas of low resource in under-developing nations where there are shortages of providers, it is still midwives first, physicians for higher risk complicated cases. So, we have this backwards and we know it and it’s not in our interest to change that because this is a capitalistic situation where we are making a business of obstetrics rather than a practice of obstetrics.

Saving Ourselves: What Does Empowerment Look Like?

LISA REAGAN: Let’s talk about the race piece, because coming into America from Great Britain and you’re coming into a country that has very deep racial divides and history of slavery is alive and well and the trans-generational trauma that still exists among women of color with what was done to women of color during slavery and afterwards, including being made to go into the basements of hospitals during segregation in order to deliver. This piece here is what I hear you speak of when you talk about teaching empowerment and what does that look like and how you cannot go to the hospital by yourself and you have to have a very solid plan for yourself long before you get to that place. How is that done?

JENNIE JOSEPH: Well we made it part of the actual delivery of the medical care, if you will. So, yes, we are measuring the belly and dipping the urine and taking the blood pressure like everybody else who is providing obstetric care, but we have woven into that care the conversations that I think are life-saving conversations.

So, for example, we want to gather whomever is going to be part of the support team and from the inception of care, start working on what piece of this puzzle can you help us fill? What do you know and what don’t you know? We will provide what we think you need to know. We will help with the health navigation, such that it starts at which hospital do you plan to deliver this baby in? Oh, well, this hospital you have a better option for this, that hospital, you may not. This hospital, the physicians are going to be willing to listen, that hospital…. We have done our due diligence as staff and providers to be up to total speed on a daily basis even as the wind changes direction, we are ready with, oh you know what, we just heard about blah blah blah, heads up. Right?

So, for example, we want to gather whomever is going to be part of the support team and from the inception of care, start working on what piece of this puzzle can you help us fill? What do you know and what don’t you know? We will provide what we think you need to know. We will help with the health navigation, such that it starts at which hospital do you plan to deliver this baby in? Oh, well, this hospital you have a better option for this, that hospital, you may not. This hospital, the physicians are going to be willing to listen, that hospital…. We have done our due diligence as staff and providers to be up to total speed on a daily basis even as the wind changes direction, we are ready with, oh you know what, we just heard about blah blah blah, heads up. Right?

So, it is a health navigation program, if you will. It is a “let’s make a birth plan that is practical and achievable.” It’s, okay, Dad, if you’re going to be right there, make sure as the baby is delivered that you get really close in and help get the baby skin to skin. Grandma, you know, if you’re going to be the one, remind them just as the baby is being delivered that you don’t want the cord cut right away. We plan ahead on the things that are achievable and doable, and essentially by the time we get a mother to term, her entire family is her doula. She doesn’t even need a doula, because everyone has been trained to be such. Whoever is going to be in that birth room has a piece to play. It is not about who is going to rub her back the best, it is about who is going to be running interference, who is watching the IV to make sure what’s in it is really what is supposed to be in it. Who is watching the monitor to see when the nurse says, oh the heartbeat is so slow we’re going to have to do a c-section and they can hear 140 beats per minute in plain hearing because they know what they’re looking for.

Tricks and under the radar sneaky stuff, that’s what we’re doing. This is an unfortunate situation we find ourselves in, but again, I call this life-saving information because the other side of this is a mother or family that are going into labor and delivery totally oblivious, clueless, and at the mercy of these statistics. These statistics aren’t in a void, they aren’t just popping up recently out of nowhere. This is continual and steadily the same, even at time when the rates improve overall, the disparity is usually the same, if not widening. This is important to recognize.

So, with these kinds of factors, we are doing what we consider front line work in preparing mothers of all races, of all backgrounds, to be able to fend for themselves in the hospital environments and also to be able to help them understand what they need to do to get their baby to term. We’ve been very successful and our data shows every year, we barely have a preterm baby out of a very large population of women who are high risk for preterm birth and we have very few incidences of morbidity. We do see the occasional woman with preeclampsia or with diabetes, but not like you’d expect given the women that we’re dealing with, the majority of whom are living in a food desert, are completely working two to three jobs, are stressed, are overwhelmed, are totally unsupported much of the time, and yet, they thrive. They thrive as far as their own physiological health. Their babies are a healthy weight. Their babies are breastfeeding. They are bonded and they are so connected.

So, again, the genesis of this work is not about whether we can speak a particular language well or we understand the culture of the Chinese woman, it is a matter of we have created the cultural competency is in understanding how this woman and her family can get through this healthcare system of ours safely and out the other end. That’s our work. And having an access point to that has turned the tide of the statistics in our area. Women that don’t attend our clinic are still having the same outcomes that they’ve had for decades because they may be seeing regular private physicians. They may be going to health departments, community health, where ever they go, whatever efforts and measures those other agencies have put into play, it hasn’t changed the statistics. So we definitely know the pieces that are missing are the pieces that acknowledge that the racism, classism, sexism is in play, but give people real tools with which to handle them. That’s why I am stressing that we have to talk about what it is in order to be able to mitigate it.

Insights from Intentionally Serving High-Risk Mothers

LISA REAGAN: You purposefully opened your clinic in an area that would allow you to serve high risk mothers.

JENNIE JOSEPH: I did.

LISA REAGAN: Since then, I was saying earlier, before we started recording, that you’ve done some real myth-busting, some cultural myth-busting because of where you are. Can you speak to that a little bit? I know the medical model’s defense for itself is, :oh,well, you know, women are sickly or diabetic or overweight.” You are saying that is actually not all true and not your experience.

JENNIE JOSEPH: The blaming of the women is absolutely our experience, even now. I am going to give you a quick story in a second that will illustrate my point there, but what we did was we made sure that we went to where the worst outcomes were to see if the impact of our work, you know, would be really born out. Prior to that, our clinic was in a more affluent neighborhood as part of our birth center practice and the women would come to the birth center for the same services as the Easy Access Clinic, but it was housed in the birth center environment.

I realized pretty early on that what was important was listening to what the mother said they wanted and very few of them wanted a natural birth. As a midwife, I was horrified by that, but once I got over myself, I realized it is not about me. I am doing patient-centered care and the women wanted a hospital birth because they want the option of pain relief. They want the option of staying a couple of days. They want the option of ringing a bell and getting some good food to eat. They want the option like anybody else.

So, once we have moved the center to the neighborhood, it was because I could say very clearly and categorically, “I am not asking you to deliver at anybody’s natural birth center. You may come here for clinic and go to the hospital for your birth and come back postpartum” — and immediately women warmed to that idea and we’ve had a complete traffic jam ever since. I mean, we can barely get people in. They wait weeks to get a new appointment now because it is so packed. This is obviously what the women wanted.

So, that was one thing. The second thing was the midwifery piece. They’re not interested in midwifery necessarily; they’re just interested in somebody treating them right. Like all of us, who wouldn’t want to be treated right? So, again, that was something else that just putting the clinic in that location, it was clear. We came here on purpose. Everyone else was leaving; all services and resources are running out the door, but here we come. But that meant then that we had more credibility and the trust was built very quickly. The connections were made very strongly and are still in place. We have been open in that location just over two years, and like I said, it is like packed solid over there. So that was another thing.

But then the last thing again was applying some compassionate non-judgmental listening, some understanding of, “We see you and we know what you’re dealing with. We recognize that it’s true. You’re not crazy. You are dealing with some real ridiculous nonsense here and I am sorry. So let’s at least help you to get to the other end of this pregnancy with the best outcome that you need for yourself. What do you want to do?”

That approach, literally, it seems if I was to be a little facetious, closed up all those cervices that were letting babies fall out at 28 weeks, because we don’t have our babies until 40 and 41. Left alone, this seems to be the outcome. The women will go past due sometimes much to their chagrin and they’re quite annoyed with me that the baby is not here yet, but they are also very clear that they are optimum health, they are prepared and ready to go. They know what to do to defend themselves and how to take care of themselves and they’ve proven it is because our cesarean rate is 10 points lower than everybody else in the area and we don’t even go to the hospital as midwives. Sometimes we don’t even have doulas to send with them to the hospital, and yet, they thrive.

So, let me just give you a quick illustration. When we’re busy, sometimes there’s a little bit of a wait. I have been running about a two hour wait time at the clinic. One of the mothers came in one day and she was actually laboring, but we didn’t realize it. By the time she got back to the exam room, she was really uncomfortable and she said she had a funny tummy ache and a back ache and such and this was her second baby. I examined her and she was nine centimeters dilated and the water bag was bulging. I said, okay, “we’re going to have to get you over to the hospital real quick.”

We called an ambulance and we got her in the ambulance probably about 20 minutes later and I said, you know what, I better go with, because I’ve got a feeling that we’re not going to make it. So I went with her and rode in the ambulance and baby was born about five minutes into the ambulance ride. Nothing went wrong, beautiful birth. Baby came very nicely, a couple of pushes and we were done. So baby went skin to skin with Mommy because we’re in the ambulance, in the back of the truck. We hit the hospital and this woman who is perfectly fine and happy as a lamb, baby is snuggling in with mother, breathing, everything is normal, and we hit the hospital and everybody starts running like chickens, because it is a maternity hospital, and you know, it’s a shock that there is a mother who just had a baby coming into the door on a gurney. All of the trouble that we had, all of the confusion that we had, that baby was happily snuggled up against his mother’s chest. She wanted to breastfeed, she was excited about the possibility. She was strong, healthy, and ready to go, but do you know, by the time they transferred the mother upstairs to the labor and delivery, somebody chose to put a bottle in that baby’s mouth.

LISA REAGAN: Wow.

JENNIE JOSEPH: This is what I’m talking about when I talk about the institution. The fact that the baby was born outside the hospital meant that all of these different things have to be done to ensure that the baby was okay. The suggestion is that outside of the hospital means the baby is not clean, the baby has got an infection or the baby is in jeopardy. The husband who followed behind in the car wasn’t allowed in the room because mother was admitted from an ambulance with a baby already delivered. All of these protocols and wieldy policies cause all this confusion. It was a big to do. Oh my gosh, the baby was born before the mother put foot in the building.

But worse yet and the part that really I found so painful, was that child was put on a bottle when mother wanted to breastfeed. The only reason that could have happened is because somebody decided, “well, she had a baby in the ambulance where she shouldn’t have and that baby now must be hypoglycemic,” which it wasn’t. Do you see? So these are the kinds of constraints and restrictions and power plays that undermine and overwhelm people. Now, I am happy to report this woman is still breastfeeding. The baby is six weeks old and she continued to breastfeed despite that very shaky start. But if you think about it, because she was in an ambulance, she actually got an empowered birth without any intervention or any interference, but that was sort of taken right back and she was put duly in her place as was her baby once she got the “care” that she was supposed to have had from the beginning. So these sort of nuances, they’re subtle, and we don’t really take much time to think them through or break them down, but this is the way and the continuation of the power over people. In other words, it is the antithesis of patient-centered care, but it is deadly.

Change Is Coming: From the Grassroots Up

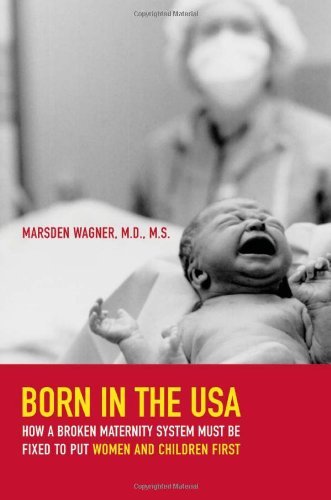

LISA REAGAN: You know, Marsden Wagner, MD, talked about the cascade of interventions in hospitals for birth 20 years ago. I think it was even on CNN at one point in 2006, I think about this. It is shocking to me that it is 12 years later and you’ve been doing this work for a couple of decades and we’re still here.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Right.

LISA REAGAN: So I am wondering, what is going to crack open this capitalist system that is killing people and how are they going to be held responsible when there is clearly another way and there could be better outcomes.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes, well, I am not sure if we will ever break the system, because the system is very well-designed and it is doing exactly what it was designed to do. What I think we might be able to achieve is getting to providers who are going to be able to stand up and say, “No, enough,” or, “I won’t have that.”

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes, well, I am not sure if we will ever break the system, because the system is very well-designed and it is doing exactly what it was designed to do. What I think we might be able to achieve is getting to providers who are going to be able to stand up and say, “No, enough,” or, “I won’t have that.”

So we see little wins here and there. Oh, L&D decides, okay we will allow skin to skin if everything is normal. Okay, that’s a win.

You know, the majority of people are getting the skin to skin care. But then I am going to just bring it back a second to the institutionalized side of racism or whatever, that says oh, well you’ve got this type of insurance and you don’t look like you really know the difference, so you don’t get the skin to skin or you don’t get it for as long. This happens all day long. Right?

So do you see where we’ve kind of got ourselves so befuddled with pieces of policies that are sort of half in place matching certain people and not matching others. So, again, I think it is going to come down to individual providers and the providers are going to have to understand or be taught what’s wrong. It is easier for a provider sometimes to just say, “There is nothing wrong here. This is what I know. This is normal. This is how we do business,” and leave it at that. If they don’t know and understand the relationship between these behaviors or these policies and the outcomes, we cannot really blame them for what we’ve got.

I feel like that it’s imperative that we start educating them. Not about “you need to do this drill and that drill.” Those drills are great. We should have been doing drills anyway, if you ask me. But not the “oh, we’ve got our reduced numbers now of poor outcomes because we do drills.” No, we need to understand how the system inherently is causing the problems in the first place.

So not just the labor and delivery floors, it is not just the interventions necessarily, but from the face of the prenatal care, even the preconceptual care, access to that care, remember access is my number one tenant, the collaborative work between the outside providers and the in hospital providers, the collaborative work between the outside providers and the maternal fetal medicine specialists, the perinatologists, the collaboration between the support agencies and the helping agencies, all of the holistic care for this woman and her family needs for us as providers to say, “Oh!”, as a group, in tandem, we all see our piece and we are all willing to now address our piece by, first of all, learning where the system fell down and how you ended up in this position in the first place. Right?

So, while we talk about, well, certain areas, for example certain urban or rural areas are under-served or don’t have enough providers or hospitals are closing, then we go, oh, and throw our hands up. Unless we see how our individual relationship with these things plays out, we don’t feel like it’s our problem.

Again, I don’t hold out any hope for the overall over-arching system to change, but I am certainly hopeful that provider by provider, group by group, agency by agency, university by university, we begin to open our eyes to this supposedly intractable problem of disparities, particularly racial disparities in perinatal health is only going to change if we agree that there’s a problem and the cause of the problem is identified clearly. That’s what I think needs to happen.

That means everybody should be having beyond the one hour CEU of cultural competency. Everybody. From ancillary staff on through. Everybody needs to understand anti-racism. Everybody needs to have a history lesson in terms of how we got here. All of these ways of being that have come up through the centuries have come up through the decades need to be unraveled. We have a problem and it is not going to be solved by, “well, if the system changes, we should be good.” It is going to come from our individual practitioners, providers, groups, organizations saying enough, there is something wrong here. We see it, we call it out, and now we’re ready to look at how to address it so we can change it.

Preparing for Both Progressive Change and Predictable Backlash

LISA REAGAN: Well, history would say that pioneers like yourself are in for some backlash.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Oh yeah.

LISA REAGAN: Have you experienced any?

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yeah.

LISA REAGAN: We don’t have to go there if you don’t want to.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Oh, no, it’s fine. I mean, I think people are very generous and they talk sweetly and nicely with me, but at the end of the day, I know there is some concern about why we are doing this. We can’t all just go around giving free care or we can’t all just open up our doors to anybody who is breathing. We can’t all do blah blah blah. Yeah, it’s true. We can’t. So then what else are we going to do? If something as simple as letting people in the door is enough to drop our county prematurity rate. For black women, it is anywhere between 18-20%, our personal prematurity rate at my clinic if it gets up to 5% it is unusual. The same population of women, the same zip codes, everything. I am not talking about my work or my approach has dropped the points, couple points here and a couple points there. I am not talking about that. I am talking about a practical eradication and I haven’t got any fancy technology. I haven’t got any expensive medication.

Our women who don’t have a preterm baby are not getting those expensive injections and running up and down to maternal fetal medicine every ten minutes. They just are going on ahead and having a healthy pregnancy. So there is a lot of concern, I think about, “Well, your model is all well and good Jennie, but not everybody can do it.” Well, I don’t know, because yes, we struggle financially, but on the other hand, we still manage and we are doing the interventions that we have put in play don’t actually cost any money. It’s the same staff. We’re still a skeleton crew. We are way understaffed, but we manage because the things that we provide are part of just being in the building and breathing for our 8 hour shift.

It is not extra cost-wise to say something nice to somebody. It is not extra to listen. I have found that instead of holding up the exam room and listening in the exam room, we do the quick visit for the medical care that’s needed and then women go to talk to other women and other providers in other areas of the building and they work their way around so that by the time they finish their entire visit, they’ve talked to several of us at different points on different topics in different ways. Now all of a sudden, they’ve had a very deep and thorough time and opportunity to share and opportunity to learn, opportunity to be empowered and it costs the same money. We use peer and paraprofessionals to do most of our work because people relate to their peers. We don’t have a big tray of big expensive practitioners sitting in the back offices twiddling their thumbs and waiting on patients. We don’t do that. It’s an interactive experience. It’s a family-centered experience.

We all have a lot of fun. There’s a lot of giggling and silliness going on. We lighten up the whole atmosphere because everybody would be stressed and miserable otherwise. And somehow, that has turned the tide and changed the outcome so drastically that, again, like you mentioned at the beginning, people are asking me, well, what is it that you do? And all I can tell is that it’s a way of being, it’s not a way of doing. It’s who we are and how we stand and how we show up. We are here for one express purpose and that is to help you get your child and yourself to term healthy. That’s it. By any means necessary, what are we going to do to get that done? How can we help support you to get there? What do you want? What do you need? That’s it.

March for Moms — Black Maternal Health Week — Creating Change

LISA REAGAN: We’re getting near the end of our hour, but I want to connect some dots. We have the March for Moms coming up on May 6, 2018, and this is not only addressing birth outcomes in America, which by the way, for all women, you’re more likely to die in childbirth, seven times more likely than your counterpart in Italy or Ireland. That’s everybody. Birth in America compared to our European counterparts is getting worse. The numbers have gotten worse in the last ten years. But this March for Moms is looking at the whole picture of birth, of we don’t have paid parental leave…

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes.

LISA REAGAN: How do we expect mothers to recover from a birth? Most of them have to go back to work in two weeks and our counterparts in other countries usually get six weeks to six months, some get a whole year. How are we supposed to breastfeed with workplaces that are not supportive of breastfeeding at work, even if you could find the childcare you need to return to work. So the whole system, it’s not just the medical model. The social support for bringing a child into the world for mothers is nonexistent here in the United States. I just want to acknowledge that because I feel like I have been in this bubble for 20 years trying to figure out what is happening and it took a long time before the big picture view/New Story emerged. Oh, look what we’re trying to do inside this impossible situation.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes.

LISA REAGAN: Inside this immovable system and this intellectually indefensible way of treating human beings. So I am just wondering if you could just kind of lead us out and tell us what is next? I have heard you caution activists and midwives and birth workers to be careful about the burnout that is possible right now with the intense situation that we’re in because there is so much undoing that needs to happen along with the creating of this new model.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Yes. There is definitely that danger and there is no blame or judgment being cast on providers or practitioners who can’t or won’t come into this change. Even the nurses, again, I really feel compelled to champion the nurses. The nurses are doing an amazing job handling these deliveries on their own essentially and no acknowledgment whatsoever, so it very difficult for them to be able to… there is no support systems in place. So we have to create our own support systems as we go along.

I think there is a lot of trauma and PTSD around birth in America for everybody, not just women of color or women of low income, or marginalized women, but I do think that it is important to recognize that the only reason we have these kinds of convoluted systems are because initially physicians, you know, in the early 20th century decided that they could make money around birthing women, and hence twilight sleep and knocking women out and tying them to the bed. All of these kinds of practices came about from, oh there is a certain amount of money that could be made and the volume, build the volume, and keep control. Keep power over the birth episode, if you will.

Now I am looking at it from an angle of what can we do individually because I think that is the safest place to start and maybe the slowest part, but even inside of existing practices and existing programs working with hospital systems that are already in play. We can do a little bit. We all know the value of a doula, for example. Finding a doula, supporting doulas, training doulas, certifying doulas, or helping families be their own doulas, helping others support birth and keeping that education going.

The other thing that I am really keen to see is that we really engage peers and paraprofessionals and stop being all territorial about our credential. Sometimes the best work is done by people who are from the same communities that we’re trying to serve. Those women and men who are really genuinely concerned about their family and friends, they are the ones who are most interested in learning and navigating and supporting through systems like that. And in turn, the providers get support from these families and these community members because they want to work to help those providers be able to be viable and you know, to not have that burnout and to go away. It is not in their best interest if an organization or a clinic is up one day and gone the next. Right?

So, we can be really strategic about how we make this work, this movement that is building slowly can be built with more intention towards really looking at highlighting what the wrong things are and then also being willing to admit that the things that we may have said formally aren’t actually true. Yep, it would help if everybody ate better, not just one particular group of women. Who eats better in America? This is America. Obviously, we don’t eat very well, period. So casting blame on women who don’t eat well because they live in the food desert is not very helpful.

Yet, looking at those bigger pictures and those peripheral pictures may be easier ways to begin this change and bring these movements to, you know, more fulfillment. I am all for any willing provider, any willing supporter, anybody do your part even if it starts, you, yourself, your family, your direct circle of influence so that we can begin to shift and hopefully then, at some point, the movement will build enough momentum that we start tackling the system. But I don’t think we are going to get it from the top down, it’s just going to be grassroots just like La Leche League was grassroots, just like, you know, the ICAN networks, all of these movements, they came from grassroots up.

The key is now are we able to engage the people who are not directly effected to join these movements and participate from the perspective of helping those of us that are particularly suffering and are in mortal danger because of the lack of action around these issues. That’s where we need change. So where we had the birth activists fighting for the birth and the labor room and the intervention reduction, now we’re saying, oh but there are so women, it is not just about interventions. These women are dying. This is important and we need to now be able to make sure we focus our movement to that particular issue. If any one of us are in jeopardy, we’re all in jeopardy. Hence, we can all help each other working towards this goal if we’re strategic about it and if we’re realistic about it and again, I think coming from the grassroots upwards.

LISA REAGAN: So where can people find you online?

JENNIE JOSEPH: I’m easy. My name, jennie@jenniejoseph.com is my email and http://jenniejoseph.com is my website. I spell “Jennie” J-E-N-N-I-E and that’s always the best place to start. I also have a website called http://perinataltaskforce.com. That’s my national perinatal task force, which is my grassroots organization where like minded people are coming together, state by state, to say, “I’m here, I’m doing my part. This is what I do. Let’s connect.” So there are ways to get involved. There are ways to learn more. Every Mother Counts is a really great organization that is working on policy and change in maternal health, not only around the world but in the United States as well and that’s http://everymothercounts.org. So those are some places to jump off, but there are a wealth of organizations and interested folk who are fighting this fight and I think we are beginning to make a difference. We are beginning to be noticed. We are beginning to be heard. So I appreciate the opportunity to speak about this issue today and to reach the audience who are interested in this work. So thank you Lisa.

LISA REAGAN: Thank you. I just want to throw out a few more resources. If you’re looking for a March for Moms near you or want to know about the one in Washington, that is May 6, 2018 and www.marchformoms.org and http://improvingbirth.org is where you can for more resources on those marches and then upcoming this week, we have the Black Maternal Health Week. The first annual one is April 11-17 and you can find resources at http://blackmamasmatter.org and if you’re listening to this call and it’s been downloaded somewhere and you’d like to read the transcript, you can go to https://kindredmedia.org to find us there. So thank you so much again for coming on and talking to me and for all that you’re doing. It’s just wonderful to hear from you and connect with you.

JENNIE JOSEPH: Thank you for having me.

Photo Shutterstock/Samuel Borges Photography