Placefulness is deep attention to what arises from our places and is not simply a kind of romanticism of nature. We are embedded in the natural world, emerge from it, and should witness the changes we see occurring…

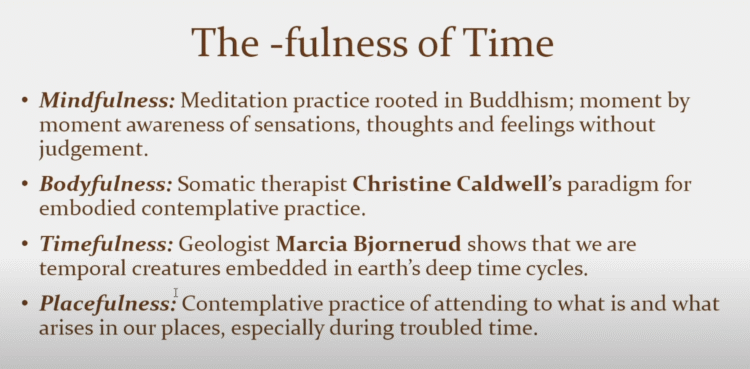

With the dawning of this inhumane age, I believe cultivating a deeper sense of place might be a powerful practice for tending to our homeplaces while equipping us with the resilience to weather the coming storms. What I am calling “placefulness” encompasses a range of contemplative practices that witness, attend to, and reflect on what is and what is arising in our places, especially during troubled times.

I first put the words religion and ecology together while I was pacing the stacks in the basement of the Brigham Young University library. I came across the Harvard University edited volumes on Religions of the World and Ecology (1996-1998). As an anthropology major, I was interested in how culture shaped ecologies, and as I struggled to craft my own ecological spirituality out of obstinate stone of my Mormon religious upbringing, these two words lit a fire in my life.

I went on to earn master’s degrees in forestry and theology from Yale and worked directly with Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, the conveners of the conference series that led to the volumes. During a forestry field trip to Europe in 2011, I stood slack-jawed in a Slovenian forest attached to a Carthusian monastery. This experience planted the seed of my PhD dissertation, and at the beginning of 2024, I published my book Dwelling in the Wilderness: Modern Monks in the American West.

The book outlines what I learned about sense of place from monks at four monastic communities in the American West. Monks take a vow of stability, a vow that weds them to place and to the monastic community. Early Cistercian Abbot Stephen Harding (1050-1134) saw this vow meaning that his fellow monks should become “lovers of the place.”1 As I found, many monks have deep affection and commitment to care for their monastery landscapes.

European-descended peoples in North America, like me, tend to live with a wounded sense of place. It has been re-placed by mobility, commodity, and sentimentality. As philosopher Vince Vycinas once wrote, “[W]e are homeless even if we have a place to live.”2 In the West, consumerism is as much driven by manufactured needs as it is by a longing to belong. One of the insights of the field of religion and ecology has been that the Anthropocene, the metaphorical epoch of industrial human pervasiveness, is as much a crisis of meaning as it is a crisis of ecology and extinction.

It is a common refrain in the field of religion and ecology that we will not work to protect what we do not love. The contemplative and spiritual ecologies that have emerged from this field have put a strong emphasis on the sacredness of the world. But as we know, the ecological crisis is going to impact particular places differently. To deepen our relationship with our places, their histories and communities, is therefore a tactic for protecting them from harm.

With the dawning of this inhumane age, I believe cultivating a deeper sense of place might be a powerful practice for tending to our homeplaces while equipping us with the resilience to weather the coming storms. What I am calling “placefulness” encompasses a range of contemplative practices that witness, attend to, and reflect on what is and what is arising in our places, especially during troubled times.

Fullness

Readers are probably familiar with the term “mindfulness,” the powerful practice of attention and presence derived from meditation practices developed by lineages of Buddhism. I understand mindfulness as emphasizing the cultivation of a deep awareness of what is arising out of one’s mind and body at any given moment without judgement. On the path to Buddhist Enlightenment, mindfulness, or Sati, leads the practitioner to samadhi, a deeper penetration into the reality of impermanence.

Geologist Marcia Bjornerud’s book Timefulness shows how deeply embedded we are in Earth’s mindboggling deep time. She takes us on a tour of the 4.5-billion-year history of our Earth and shows that every place is an inheritor of this unfolding deep time. In our modern globalized world, history and time seem to vanish with the next great thing, and looking back is discouraged as a kind of quirk. But standing near the shore of Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin, during the annual spring sturgeon count, Bjornerud marvels at the joyful faces of many people who seem to have come out just to witness firsthand these ancient fossil-fish. As Bjornerud writes, “The past is not lost; in fact, it is palpably present in the rocks, landscapes, groundwater, glaciers, and ecosystems.”3 Aldo Leopold’s dictum to “think like a mountain” includes not only the spatial dimension of relating to fellow creatures and their habitats, but also the seasons and changes that are so patiently endured.

Placefulness is deep attention to what arises from our places and is not simply a kind of romanticism of nature. We are embedded in the natural world, emerge from it, and should witness the changes we see occurring.

To Be Rooted

Biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann sees place and landscape more generally as a core theme of the entire canon of Hebrew scripture. He writes, “In the [Bible] there is no timeless space, but there also is no spaceless time. There is rather storied place, that is, a place that has meaning because of the history lodged there.”4 The Peoples of the Levant were covenanted to the Divine through places: Jacob/Israel wrestled with an angelic person on the Jabok River, and the placename Penuel means Face of/facing God. Many passages in the Hebrew Bible begin or end with the name of a place, or the origin of that place’s name. Stone altars, groves, and mountain peaks were places of contact with the Divine or the ancestors and their stories.

Biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann sees place and landscape more generally as a core theme of the entire canon of Hebrew scripture. He writes, “In the [Bible] there is no timeless space, but there also is no spaceless time. There is rather storied place, that is, a place that has meaning because of the history lodged there.”4 The Peoples of the Levant were covenanted to the Divine through places: Jacob/Israel wrestled with an angelic person on the Jabok River, and the placename Penuel means Face of/facing God. Many passages in the Hebrew Bible begin or end with the name of a place, or the origin of that place’s name. Stone altars, groves, and mountain peaks were places of contact with the Divine or the ancestors and their stories.

This biblical placefulness is not a necessarily akin to a contemporary nature spirituality, but a deeply sacred geography where a people’s claim to the land was rooted in encounters with the Divine. Layered over this history is a tension between the motifs of the garden and wilderness, starting with the very first chapters of Genesis where Adam and Eve are exiled from Eden. The entire arc of the story of Israel might be said to involve God luring humanity back to the garden through covenant, obedience, and justice.

For this reason, mystic philosopher Simone Weil wrote. “To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.”5 Rootedness was a central idea for Weil, whose life was cut short by her radical asceticism. Her emphasis on rootedness grew out of her conviction that humanity’s increasing uprootedness was causing a troubling malaise among Western societies. This malaise has fueled our consumerist lifestyles which seek to fill a void left by our rootedness in communities and places. And the fossil fuels which power this consumer society are the driving force of ecological breakdown and the climate crisis. Returning to place might mean returning to our roots, in other words, recognizing that what is truly worthwhile is right in front of us most of the time.

Singing the Land into Being

While humans are a peripatetic species, wandering on our two legs to almost every continent before the advent of farming, we also formed deep bonds with our regions, routes, and places. As David Abram writes, our symbolic consciousness, which enabled us to read the landscape as hunters and foragers, facilitated the development of language and writing. The first ideographic languages which used characters instead of syllabic symbols such as Chinese, drew heavily from the day-to-day life of living close to the land.6 The personhoods of place nurtured the tender shoots of our humanity from our earliest moments of consciousness and are reflected in creation stories from around the world.

There are of course many examples from Indigenous peoples all over the world of deep inseparable relationships to place. I want to mention at least two. For people living with the lands of their ancestors, places are rich with personhood, memory, and story.

English travel writer Bruce Chatwin’s book The Songlines explores aboriginal understandings of place in Australia (from his limited perspective). For Indigenous peoples of Australia, during the “Dreamtime” a primordial every-when, the Ancestors sang the world into being along trails called Songlines.

Within these cosmologies, one’s Dreaming is the animal connected to the very first Ancestor whether it be Kangaroo, Lizard, Bandicoot, Honey Ant, or Badger. Most Dreamings are animals, a few are plants or trees. An initiated person receives a portion of a Songline that traverses the first track of their Dreaming. The tempo and melody of the Songline express the topography of the place. Forms of the land are a remnant of one’s Dreaming’s first movements, and the features and contours of every place reflect the stories from that sacred walked-on canon.

It is hard for me to imagine being so knit to a place, but for the oldest culture on the planet, there is a sense not that the land belongs to them, but as Bob Randall, a Yankunytjatjara elder often says, the people belong to the land. An awareness of the rhythms and beings of the place orients people toward a long view of history, ancestry, and deep belonging.

A Landscape that Teaches

Places can also be teachers. Many Indigenous place names in the American West are made with afforded features of the landscape: trees, mountains, valleys; or they speak of activities that take place there like harvesting, council, or hunting. For example, in Western Apache place names, Tséé Chiizh Dah Sidilé means Coarse-Textured Rocks Lie Above in a Compact Cluster. This is a descriptive name for the features of that place. However, these descriptive placenames are laden with stories and those stories have taught the Western Apache how to live for time immemorial.

The collective history of the Apache has accumulated in these places, and they speak their lessons to the people. In Keith Basso’s account of these places in his amazing book Wisdom Sits in Places, his informant Ruth gets visibly uncomfortable as they pass a place in their car and she says, “I know that place, it stalks me every day.” This is because at that place a story is told of a man who attempted to commit incest with his stepdaughter. In Ruth’s case the place reminded her of an assault she suffered by someone close to her. The wrongness of the act is written in the landscape which gave her strength to seek justice. To put a person in their place, so to speak, one need only recite a particular place’s name, and its lessons will shoot like an arrow into the mind of the interlocutor.

Learning the Liturgy of Place

My own writing has been oriented toward a contemplative ecology that reflects on the entanglement between the inscape of soul and the landscape (Holyscapes). In my evolving practice, I want to immerse myself in the liturgy of place here at Vancouver, British Columbia. My walks attend to the cycles of the stars, sun, and moon. I am learning the rudiments of the astrological archetypes and Greek stories that accompany the constellations. I am attuning myself to the cycles and patterns of season and weather, the features of topography and surficial geology. I am slowly learning the Latin, common, and Indigenous names of plants, animals, and fungi. I am using an app to learn the melodies of the avian soundscape. I am noting the memories, lessons, experiences, symbols, and rituals that embed themselves in mundane places. I want to be a participant and not just an observer in the ongoingness of both time and place.

Restory-ing Place

In academia, we love coming up with new terms to describe our world. The sciences and social sciences have distinct vocabularies. Unfortunately, many words in the sciences and humanities are dissociative—they disconnect the speaker from the referent. Even words like environment, ecosystem, and ecology were coined by a culture without a home. They invoke abstract and universal spaces. I learned this caution from agrarian writer Wendell Berry who writes:

No settled family or community has ever called its home place an “environment.” None has ever called its feeling for its home place “biocentric” or “anthropocentric.” None has ever thought of its connection to its home place as “ecological,” deep or shallow. The concepts and insights of the ecologists are of great usefulness in our predicament, and we can hardly escape the need to speak of “ecology” and “ecosystems.” But the terms themselves are culturally sterile. They come from the juiceless, abstract intellectuality of the universities which was invented to disconnect, displace, and disembody the mind. The real names of the environment are the names of rivers and river valleys; creeks, ridges, and mountains; towns and cities; lakes, woodlands, lanes, roads, creatures, and people.7

As a scholar and writer, I have a lot to learn from this caution. Placefulness embraces science, but also a deeply lived sense of home. It is not a replacement for developing intimate relationships to particular landscapes, but a description of a practice that does.

In cultivating a sense of place, we may be passionate about restoring ecologies that have been damaged by colonial and extractive, or perhaps just careless, practices. Ecological restoration benefits local biodiversity and ecosystem function, and it is a major part of the conservation movement’s toolkit.

Yet, within some restoration paradigms, restoring an ecosystem means choosing a baseline that reflects an ecology before humans entered relationship with it. Or it might ignore Indigenous contributions to forming the ecosystem as keystone species in the first place. For many Indigenous restoration projects, ecologies are home-places, not pristine domains of Nature, and thus restoration almost always includes the people who depend on them.8

Thus, as a tool of placefulness, I think it is important to shift our understanding of restoration to one of re-story-ation, a repairing of our understanding of our place within a given ecology, rather than just an act of public penance before the God of Nature. Ecological re-story-ation could be a form of public ritual, which is how ecologist Stephanie Mills understands this important tool:

[The act of restoration] gives [people] a basis for commitment to the ecosystem. It is very real. People often say we have to change the way everybody thinks. Well, my God, that’s hard work! How do you do that? A very powerful way to do that is by engaging people in experiences. It’s ritual we’re talking about. Restoration is an excellent occasion for the evolution of a new ritual tradition.9

Restoration and re-story-ation are important tools in our local toolkits, and understood as ritual, they are both ecologically and spiritually regenerative. But I also think they will become essential methods for listening to what the land is asking for in a changing climate. Restoring historic baselines will be essential in some parts of the world, but in others we will need to experiment with new assemblages of species, novel ecosystems. Placefulness, as a practice of attending to what is and what is arising in our places, might be as much about tending to what needs healing as about making space for the unknown.

Troubling Place

It is also important to confront the ways that a place can be weaponized. Deep reverence for places can be caught up in conflict. Control over certain sacred places has been enlisted by ethno-nationalist agendas. For example, in 1992 Hindu nationalists demolished the Babri Masjid mosque because they claimed it was built by Muslim invaders over a previously occupied Hindu site. And Israel and Palestine continue to wrestle over each nation’s deeply invested identity with their home place.

Placefulness also grapples with the West’s egregious imperial and colonial history. In Vancouver, where I live, the beloved forests where I walk, the parks and neighborhoods are all part of the traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. To go into the forest and see only a natural place is to negate the fact that these are cultural landscapes whose ancient stewards have been stripped of their claims by force.

Like any spirituality worth its salt, placefulness then should attend to the good, the bad, and the ugly of the places we live. Placefulness should be able to grapple with the toxic dimension of sense of place as exhibited by ethnocentrism and the ravages of wildfire, extinction, and climate chaos that are dawning on every horizon.

References

1 Stephen Harding (12th Century) Exordium Parvum, Website:

http://www.ocso.org/resources/foundational-text/exordium-parvum/

2 Vincent Vycinas, Earth and Gods: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Martin Heidegger (The Hague, Netherlands: Springer, 1969), 268.

3 Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018), 162.

4 Walter Brueggemann, The Land: Place as Gift, Promise and Challenge in Biblical Faith, 2d ed. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2002), pos. 3051.

5 Simon Weil, The Need for Roots (New York: Routledge, [1949] 2002), 41.

6 David Abram, Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World (New York: Vintage, 1996).

7 Wendell Berry, Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 1993), 35.

8 Kyle Powys Whyte, Joseph P. Brewer, and Jay T. Johnson. “Weaving Indigenous science, protocols and sustainability science.” Sustainability Science 11 (2016): 25-32.

9 Gretel Van Wieren, “Ecological Restoration as Public Spiritual Practice.” Worldviews 12 (2008): 237-254.

Reposted under Creative Commons License and with permission from Ecozoic Studies.