How Attachment Theory Explains Trump’s Success – And Hitler’s Too

Donald Trump has done it. He’s won the Republican nomination, having convinced enough Americans that he has the qualities needed to be a Presidential candidate. The rest of the world is looking on with disbelief, confusion, terror and derision.

Many commentators are firmly of the view that, given the statistics, Trump has no chance of actually being elected President, come November 2016. But in many ways, that’s irrelevant now. Trump has already changed America. He has unleashed extremity, humiliation, suspicion and blame. He has done that with a personal style that is abrasive, rude, narcissistic, belligerent, untruthful and ludicrous. Yet he has drawn support from across the USA.

How can that be explained?

Some analysts have put his appeal down to the economic struggles facing many Americans. Others have attributed it to educational divides. Statistician Nate Silver has highlighted Trump’s ability to manipulate the media. Journalists for the magazine The Weekascribe his success, alternatively, to conservative Republicans’ willingness to abandon traditional norms of governing and also to liberal Democrats’ intolerance of views that they find objectionable. The commentator Steven Poole even jokingly (or maybe not jokingly?) put it down to linguistics: Trump loves to punctuate his dazzlingly vague speeches with the thrillingly seductive morpheme ‘so’. “Together”, he says, “we are going to win so much and you are going to be so happy.” Presumably his supporters are so so happy now.

I want to add another explanation to this mix. Attachment theory can go a long way toward helping us make sense of Trump’s popularity.

I think we will need such an analysis in the coming months and years – regardless of whether or not Trump wins the election. The American political system is in meltdown. So are other political systems. The UK will shortly hold a referendum on withdrawing from the European Union. The outcome of that could well prompt a second Scottish referendum on separating from the UK. The refugee crisis currently engulfing Europe is prompting the return of very real, razor-wire boundaries between countries. Political distrust holds consequences that matter for the whole of our globe. Political distrust is driven by fear. And that’s what’s driving Trump’s success. Fear.

So what is attachment theory?

It’s an explanation of why humans (and all other mammals) seek out a sense of safety. Attachment theory helps us realise that this search is a biological drive. We humans have a physiological need to feel safe – not simply to be safe, but to feel safe. Our brains don’t believe we are safe until we feel safe.

Attachment theory first emerged in the 1950s, led by paediatrician and psychologist John Bowlby. Since then, the core tenets of attachment theory have been repeatedly affirmed. Particularly helpful has been the development of technologies that allow neuroscientists to track brain development. This new evidence confirms what Bowlby and his colleagues suspected: early life leaves a long legacy. Our experiences as babies and toddlers lay down neural pathways in our brains that determine how safe versus how risky the world seems. Those pathways are obstinately robust.

Thus, fear starts early in life. If the environment often feels scary to you as a baby, then it’s very likely to feel scary to you as an adult. That continuation happens because your brain and body became wired with enough fear sensors to keep you trapped within the physiological emotional framework your brain set up as an infant. Your brain sees no reason to question that framework. Why question reality?

How, then, does attachment theory help to explain Trump’s success?

The answer lies in appreciating the extent to which fear is driving Trump supporters. Last September, a political scientist named Matthew McWilliams gathered some striking data while completing his PhD. His findings are drawing considerable attention across social media. He found that the factor most predictive of support for Trump is authoritarianism. The surprise was that this factor cuts across conventional demographic boundaries: education, income, religiosity, age, class, region. McWilliams argues that what binds such diversity together is authoritarianism.

Authoritarianism is a type of personality profile. It characterises someone who has a desire for order and a fear of outsiders. Authoritarians look for a strong leader who promises to take action to combat the threats they fear.

In short, authoritarians are seeking a sense of safety. Their political choices are driven by an attachment need. Trump makes his supporters feel safe.

That’s why Trump supporters can hold views that can sound scarily extreme to others. Muslims should be banned. Mexico should pay to build a wall. Gays and lesbians should be prevented from marrying. In fact, let’s ban them from the country too! And while we’re at it, why not critique Abraham Lincoln’s decision to free the slaves?

McWilliams’ data are compelling because they have proven so predictive. He has conducted several large polls, and the factor that keeps coming up as most predictive of Trump support is authoritarianism. Here, for example, is the graph showing his data from the South Carolina primary. The higher a person’s score on the Authoritarian Scale, the more likely they said they were to vote for Trump. The slope of that line is so steady it’s unnerving. Little wonder, then, that Trump has won 26 primaries so far. That’s half the states in the USA.

McWilliams isn’t the only one to have highlighted the importance of authoritarianism. Political scientists Marc Hetherington and Jonathan Weiler reached similar conclusions in their 2009 book, Authoritarianism and Polarisation in American Politics. They argued that the Republicans, as the self-proclaimed party of law and order and traditional values, would inevitably prove attractive to large numbers of Americans with authoritarian tendencies. They just hadn’t predicted it would happen as quickly as 2016. But what’s happening completely fits their predicition: “Trump embodies the classic authoritarianism leadership style: simple, powerful and punitive.”

How is authoritarianism measured? It’s astoundingly simple. You just ask four straightforward questions:

-

Please tell me which one of the following you think is more important for a child to have: independence or respect for elders?

-

Please tell me which one of the following you think is more important for a child to have: obedience or self-reliance?

-

Please tell me which one of the following you think is more important for a child to have: to be considerate or to be well-behaved?

-

Please tell me which one of the following you think is more important for a child to have: curiosity or good manners?

These four questions were devised by political scientist Stanley Feldman in the 1990s. The responses that emphasise behaviour, as opposed to internal qualities, are associated with authoritarianism. Feldman’s studies showed that these four questions turned out to be so reliable in assessing authoritarian tendencies that they now form the field’s ‘industry standard’ and are regularly incorporated into all sorts of political surveys.

It was, though, earlier research that had provided the platform for Feldman’s thinking. Psychologist Diana Baumrind carried out ground-breaking work in the 1960s that identified three main parenting styles in America. Her findings have stood the test of time.

- Authoritarian parents tend to be rigid and controlling, focusing on external behaviour rather than internal experience. They expect a lot from their children, but without offering warmth or being responsive to their emotional needs. Children are expected to do as they are told, without questioning. The data showed that children raised in environments where they have such little control over their own lives tend to be unsure of themselves, don’t trust easily and have difficulty completing tasks. Baumrind emphasized that parents might adopt such a style due not only to their own personality but because they were trying to protect their child from a dangerous environment.

- Permissive parents offer lots of warmth. However, they don’t set limits or impose expectations. These children often grow up impulsive and frustrated, with difficulty in adjusting their own desires to meet those of the wider society or relationship partners. It is harder for them to adapt to the restrictions of adult life.

- Authoritative parents have high expectations of their children, like authoritarian parents. However, they also offer warmth, like permissive parents. They are responsive to their children’s emotional needs; they are flexible; they listen. Children’s internal experiences and emotional needs matter to them. These children tend to become self-reliant and independent, with high self-esteem and respect for others. They function pretty well in the adult world.

While three descriptive categories absolutely do not explain the whole of a person’s character, Baumrind’s account provides a starting point for making sense of adult behaviour that can, at first, seem bewildering. It helps us to see how a parent’s style of relating to their child intersects with that child’s attachment needs, resulting in a mindset for the child as to how risky or safe the world is.

Except it’s more than a ‘mind’-set. It is actually a biological orientation to the world. It is a reflection of the child’s early emotional experiences, which may bear absolutely no relation to the present, but which is now woven into their very physiology. Their brain is stuck in the past, filtering the way they perceive and react to the present.

What’s really sobering is that Baumrind’s research with the children started when they were 3-year-olds. Children were already of an age that “rendered them unlikely to alter their genuine, instinctive reactions.” That sounds unbelievably early to most people who are new to the science of the early years. Yet, the age of 3 years is commonly identified by neuroscientists and by attachment theorists as marking a shift in children’s developmental trajectories.

This all explains why it does not matter to Trump’s supporters whether he grasps international affairs, diplomacy or honesty. What matters is that he makes them feel safe.

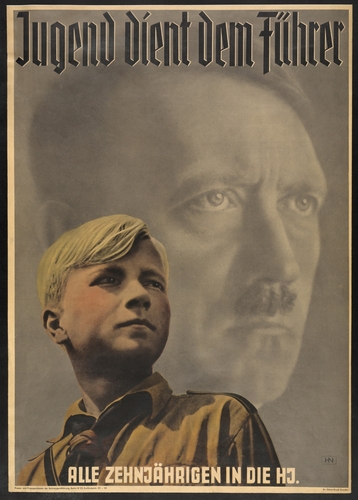

And guess what? That’s exactly the approach that Hitler took too.

Hitler made Germans of the 1930s feel safe. No, not all of them. Far from all of them. Many resisted his vision, including his fellow politicians. But Hitler made enough of his citizens feel safe. His message resonated with enough Germans to to allow the Nazi Party to prosper.

The problem wasn’t Hitler. The problem was support for Hitler.

I hope that, at this point, you might have taken a deep breath. It is very clear that I have just compared Donald Trump to Adolf Hitler. I am not, of course, the first to do that. The Mexican President,Enrique Pena Nieto, has done so, as has Holocaust survivor Zeev Hod. Commentator Adam Brown carried out a detailed policy analysis of that comparison in October 2015, and the PhiladelphiaDaily News made the same comparison on the front page of their paper in December 2015. The historians Robert Paxton and Fedja Buric have taken such uncomfortable debates to a new level by seriously discussing whether a comparison to the fascist Mussolini might be more accurate. The NY Daily News chucked Stalin into the mix.

But even with such illustrious company, you might wonder if I haven’t taken things a step too far. It is not a bit far-fetched to compare Donald Trump to Hitler? Is it not just a bit too insulting or too unimaginable? Is it not according him slightly too much power – especially as he hasn’t yet been elected President and many think he hasn’t got a hope in hell of that anyway.

No, its not. Because, as I said, the problem wasn’t Hitler. And the problem isn’t Trump. The problem is support for Trump.

In his brilliant book Parenting for a Peaceful World, published in 2005, psychologist Robin Grille carried out a psycho-historical analysis of 1930s Germany. He traces the parenting advice popular at the end of the 19th century, just at the time when many Nazi supporters would have been young children. His review shows that the most popular childcare experts were promoting an authoritarian parenting style. They recommended ignoring and even crushing children’s emotional needs, in order to raise well-behaved, obedient adults.

It doesn’t take much to start crushing children’s capacity for connection – especially if experts are encouraging you down a harsh, unwavering path of relating. You can make a pretty good start by the age of 3. By then you’ve had a lasting impact on a child’s brain. And you don’t have to be a parent to achieve that change. Institutions charged with caring for young children, including childcare, social work, orphanages and hospitals can do a lot to damage children. It’s easy. You don’t even have to intend to. Just create policies that prevent staff from meeting children’s emotional needs, make the staff ratios so high there’s too little opportunity to meet them anyway, and be sure to humiliate, exclude and punish bad behaviour.

Adults who had been raised in authoritarian settings were just what Hitler and the Nazis needed — adults who would dispense with compassion in order to have safety. Adults who could feel so good about themselves in the process.

Robin Grille makes the point that such political success didn’t require all German parents of the early 20th century to follow expert authoritarian advice. He has no doubt that many German parents were highly empathic. Indeed, when comparing autobiographical accounts of Nazi sympathisers versus Nazi resisters, he is able to identify distinct differences in the way their parents treated them during childhood. (Read Robin Grille on Kindred and watch his Parenting for a Peaceful World video series here.)

So a country – whether that’s Germany or America or anywhere else — doesn’t need all, or even a majority, of its adult citizens to adopt an authoritarian parenting style in order to wreak widespread cultural havoc. All that’s needed is enough of them. As Robin Grille puts it (pg. 120): “Only a critical mass of harsh, authoritarian upbringing is needed to skew a nation towards dictatorship and war.”

The articles currently circulating on the web that explore this issue tend to focus on ‘American authoritarianism’. And its certainly true that there’s plenty of that about. For example, Daniel Kolman (@kolman) recently tweeted that he was shocked to discover that 19 US states still allow corporal punishment in schools. I have myself previously written about the book No Greater Joy, popular amongst the Christian Right community in the USA, which advocates training babies’ behaviour by regularly beating them with a 12-inch piece of lawn-strimming cord. After the age of 1 year, the authors recommend upgrading to plumber’s supply line, which is thicker and which you can find at any hardware store, in a variety of colours for you to choose from. The book gets plenty of five-star ratings on Amazon.

A petition in 2011 tried (and failed) to ban Amazon from selling the book. A member of the UK Parliament tried to at least get its sale banned in the UK. But Amazon is global, isn’t it? Authoritarianism transcends national boundaries.

And that’s my real point in this piece. Authoritarianism transcends national boundaries. It isn’t present just in America. It is present in all cultures where humiliation, shame or violence is used to control children. It is present in all institutions where adults become more concerned about managing children’s behaviour than responding to their feelings. It is present in many of the homes in your community where parents are simply trying to do their best to raise their kids.

Donald Trump is dangerous NOT because he is now the Republican nominee.

Donald Trump is dangerous because he legitimises fear.

Leftover baby fears are oh so powerful, lurking in the dark of our neural pathways. That’s the point of attachment theory.

If you’re worried about this election, whatever country you live in, don’t fight Trump. Fight fear.

If you’re worried about world events beyond the American election, do the same thing. Fight fear.

Featured Photo Shutterstock/Joseph Sohm

Was the 3rd style of parenting correctly named? It’s seems like a mistake. Are the 1st and 3rd really authoritarian and authoritative?

Yes it is correct. Authoritative is different to and distinct from Authoritarian.

No wonder we have a generation of give me everything I am to spoiled to earn it.

I would argue that Bernie Sanders does this same thing. He’s feeding on the fears of the American people.

I would argue that Bernie Sanders does the exact opposite. Watch him at a town hall meeting: he spends most of his time listening to what people say and verifying that he understands the problem. He refuses to take a cheap shot at his Democratic rival when it distracts from the issues. I cannot say this about Donald Trump.

Mutual respect is the foundation of a healthy family and a healthy democracy. A good leader is confident enough make decisions and choose sides of an issue without pushing someone else down. I always felt like there had to be some practical justification for attachment parenting & encouraging kids to think for themselves, beyond the fact that it felt like the right thing to do.

That’s not much of an argument, and I think your comment probably qualifies as trolling. So I hesitate to ask this, and I don’t want this excellent essay by Dr. Zeedyk or the comments thread to be hijacked by a Bernie v. Hillary tangent, but can you explain why it is you believe this? I’m a Bernie supporter, I have family in VT who love Bernie, there’s a reason he’s been reelected by ever-increasing margins over the years in VT, and we hear he’s a very pleasant guy and people love working with him. He’s spreading the love, not fear. I would therefore argue he operatives in the healthy authoritative mode described above. You can learn more directly from his website: https://berniesanders.com/issues/. And have lovely day!

But how do we “fight fear?”

With compassion. Somehow.

Would be great to see this published somewhere to get more exposure– like The Guardian — as the US media would likely pick it up too?

Bravo, Dr Zeedyk …and Kindred!