Your Primal Wound: What Happened In Childhood? Part 2

Did You Experience Empathetic Parenting Or Primal Wounding?

Psychosynthesis considers a human life to move toward self-realization: “developing a committed relationship to the source of our being, a willingness to follow the call or vocation of our deepest truth, no matter the experiences in which we find ourselves” (Firman & Gila, 1997, p. 181). At all stages of life, the individual immanent “I” (non-ego) and the transcendent (Common)Self are connected. Thus, (Common)Self realization involves both personal development and transpersonal development. When things go well, we experience a continuum of growth and flourishing under natural conditions.

The mother is the initial conduit for the child of the larger ground of being. She is the primal relationship that nurtures the child’s being. Her love forms a protective shield around the child that can neutralize or at least decrease the stresses of life (Verny & Kelly, 1981).

Ideally the mother stays close by throughout the first days, months and years of life while the child’s sense of the world expands to include supportive others. Mother and others do not consider the child a defective adult but as a sensing, feeling person with agency, feelings and goals. Ideally, parents and other caregivers treat the child like a “Thou,” with reverence, honoring the needs of the child, understanding that the infant is already a person, having started his or her personhood (“hominization”) at some point during gestation. This I-Thou terminology is Martin Buber’s (1958).

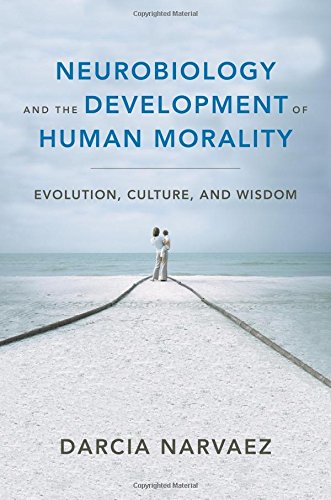

As Firman and Gila point out in A Psychotherapy of Love: Psychosynthesis in Practice (2010), what supports the unfoldment of human potential begins in early life with what psychotherapist scholars call “self-regulating others” (Stern, 1985); “holding” and “mirroring” of the child by the caregiver (Winnicott, 1987); empathic attunement from caregivers bringing into being the “nuclear self” (Kohut, 1984); responsive caregivers facilitating secure attachment (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999); loving caregivers providing “limbic resonance” that shapes the “neural core of the self” (Lewis, Amini, & Lannon 2001; Siegel, 1999); and a “mutually-responsive orientation” between caregiver and child facilitating a cooperative, caring moral self (Kochanska, 2002). These descriptions describe the appropriate environment for a child’s development.

What develops? According to psychosynthesists, the child’s spirit blossoms from the intimate union of the body and soul. The child’s physical presence must be well nurtured for the spirit to feel comfortable showing itself.

Children are born ready for relationship. In fact, after several months of development, fetuses are ready to communicate with mother and others. They are active in relationship from the start and are shaped and self-shaping by their social experience. Infants, born 18 months immature because of head size, expect a continuity of being, a continuation of the womb experience as brain and body systems are establishing their parameters and thresholds. Interestingly, Winnicott (1987) suggested that an infant may not really come into existence if the continuity of being is broken. Specifically, if maternal care is not “good enough,” absent the empathic holding environment for that child’s emergence. No child can become him or herself without the type of caregiving environment described above. When the relationship is broken, with an absent mother (emotionally, psychically, and/or physically), it causes anxiety: “hunger, pain, emptiness, cold, helplessness, utter loneliness, loss of all security and shelteredness…a headlong fall into the forsakenness and fear of the bottomless void” (Neumann, 1973, p. 75).

But most children today do not experience a continuum of empathic support. Fewer and fewer children are provided the foundations for a thriving life.

How are they wounded?

When parents and caregivers are not empathic with the child’s needs, when the child is treated as an object rather than a living, conscious human being, the child is being treated like an “it.” An empathic break occurs and the child’s developing personhood is violated. In modern societies, caregivers often have blind spots, are unable to mirror the wholeness of the child’s nature, thereby leaving out areas of being in the child’s developing spirit. Even loving parents may not be empathic, attending to the child in the way needed at the time (Miller, 1981).

Note that pain itself is not the pathology. Rather, it is the break in empathic connection that causes trauma: “It is the absence of adequate attunement and responsiveness to the child’s painful emotional reactions that renders them unendurable and thus a source of traumatic states and psychopathology” (Stolorow and Atwood, 1992, p. 54)

Many children through history have not received empathic care. Instead, they have been treated like an “It.” Lloyd deMause (1974) examined the history of parent-child relations and described six historical phases reflecting changing attitudes: (1) Infanticidal (antiquity to 4th century AD) which included infanticide and sodomizing of children; (2) Abandonment (4th – 13th century) represented by both physical and emotional abandonment; (3) Ambivalent Mode (14th -17th centuries) where children were beaten into shape; (4) Intrusive Mode (19th century) when empathy emerged but still a focus on controlling the child in every way; (5) Socialization Mode (19th – 20th centuries) when socialization focused on channeling impulses; (6) Helping Mode (beginning to mid-20th century till present) where parents became involved in empathizing and fulfilling child needs.

It seems that many parents and professionals today still have notions of young children as dumb or mindless (mode 3), leading to continued mistreatment (Chamberlain, 1994). They treat babies as if they don’t feel pain (infant circumcision) or as if their crying is reflexive instead of communicative. Many adults bring their own sense of abandonment into the caregiving relationship (#2) and pass on that trauma with unempathic care (e.g., leaving babies to cry). Even if Mode 6, Helping, were widespread, it does not represent the nurturing environment young children need.

Note that the modes cover the period of human civilization (settled societies reliant on monoagriculture), approximately the last 1% of human genus existence. Humans have been around for about two million years and civilization emerged around 10,000 years ago. So these modes are from the 1% of human genus existence. What does that matter?

“Uncivilized” societies continued to exist in parallel with the civilized and some still exist today (though globalization pressures are exterminating some). Life was and is very different for humans. Small-band hunter-gatherer societies were the type of society in which humans spent 99% of their genus existence. And these societies raise children very differently from most civilized societies. They provide the evolved nest.

Although theorists have typically emphasized vision in their discussions—“when I look I am seen, so I exist” (Winnicott, 1988b, p. 134), the first relays of empathic support and being acknowledged as a person come from other senses: affectionate touch and the sound of mother’s voice. These are part of the evolved nest.

The evolved nest is the description of the elements of the evolved holding environment. It involves not only responsiveness (the most studied and discussed) but nearly constant affectionate touch in the early years, breastfeeding on request for several years, responsive play mates with self-directed play, play in and connection to the natural world, a community of responsive caregivers, positive social support and climate for mother and child. (More here about the Evolved Nest.)

Offspring of other animals who are deprived of their typical nest are malformed (see Harry Harlow’s experiments). We have increasing amounts of data showing that humans who do not experience the evolved nest are wounded in many ways, from physiological to psychological, emotional, intellectual wellbeing.

It all comes back to mother, father, and other caregivers. To be an effective empathic caregiver of children requires one to heal the self first through self-knowledge, empathy towards one’s own woundedness, a commitment to healing and self-transformation. But it goes beyond the individual. Each parent needs to feel the support of the community and to be given the leisure needed to attend to baby’s needs. And baby needs to expand their sense of good enough holding to more than mother.

What’s an adult to do to get back on the path to self-realization? We discuss the psychosynthesis answer in the next post.

PRIMAL WOUND SERIES

1. The Primal Wound: Do You Have One?

2. What childhood experiences lead to primal wounding?

3. How to heal the primal wound

4. Fantasyland: A Nation of Primally-Wounded People

5. Tales of a Primally Wounded Society

6. Stories to Heal Primal Woundedness

REFERENCES

Assagioli, Roberto (1973). The act of will. New York: Penguin.

Buber, M. (1958). I and Thou (R.G. Smith, trans.). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

J. Cassidy, P. R. Shaver, J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (1999) (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed.) (pp. 503-531). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Chamberlain, D. (1994). The sentient prenate: What every parent should know. Pre- and Perinatal Psychology Journal 9(1), 9-31.

Chamberlain, D. (1988). Babies remember birth. Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher. p. xx

deMause, L. (1974). The history of childhood: The untold story of child abuse. New York: Peter Bedrick Books.

Firman, John, & Gila, Ann. (1997). The Primal wound: A transpersonal view of trauma, addiction, and growth. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

—-A Psychotherapy of Love: Psychosynthesis in Practice (2010),

Kochanska, G. (2002). Committed compliance, moral self, and internalization: A mediational model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 339-351.

Kohut, H. (1984). How does analysis cure? in A. Goldberg (Ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Lewis, T., Amini, F., & Lannon, R. (2000). A General Theory of love. New York: Vintage.

Miller, A. (1981). The drama of the gifted child. New York: Basic Books.

Neumann, E. (1973). The child, R. Manheim, transl. London: Maresfield Library.

Richards, D.G. (1990). Dissociation and transformation. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 30(3), 54-83.

Rowan, J. (1990). Subpersonalities: The people inside us. New York: Routledge.

Siegel, D. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York: Guilford Press.

Stern, D.N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. New York: Basic Books.

Stolorow, R.D., & Atwood, G.E. (1992). Contexts of being: The intersubjective foundations of psychological life. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

Verny, T., & Kelly, J. (1981). The secret life of the unborn child. New York: Dell.

Winnicott, D.W. (1987). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.