How To Decolonize Higher Education: Three Easy Steps And One Hard One

Often in life, we find more difficulty in getting motivated to implement a healthy practice than exists in the practice itself. Similarly, it is relatively easy for a professor to start decolonizing coursework in any academic discipline and more challenging to make and sustain the commitment to do so. I begin here describing the more straightforward task, offering three ways to start immediately. I end with a brief explanation of why we talk about decolonizing in higher education more than we do.

So what does decolonizing curriculum and instruction involve?

(1) A Focus on “Actual Decolonization”

First, faculty and students must realize and address “actual” decolonization before and throughout talking about other vitally essential and integral repercussions of it. The “actual” one relates to the original and continuing colonization of the Americas and the decimation and oppression of Indigenous people by the European invaders. The second relates to the many current social/ecological injustices, colonial practices that support them, and deterrents to the pursuit of happiness that stem from this actual event and the ongoing manifestations of it. To focus on this second form of colonization without continuing to rectify the first is full of dangers to both.

To engage with the topic of “actual decolonization” calls for engaging students in truth and reconciliation discussions about historical, contemporary, and future realities. It is about the wrongness of how we have treated Indigenous nations, communities, and individuals, and what we can do to mitigate it. It includes awareness of the resilience, courage, and leadership of Indigenous people. It requires studies that focus on authentic sovereignty and restoration of as many stolen rights as possible.

It may be best to put a course dedicated to studying this actual colonization into the first term requirements for all students. Whether it is or isn’t, however, this focus must remain part of all subsequent courses to some significant degree. Redundancy is fine and even necessary. Each session can promote a return of Indigenous sovereignty and rights via the subject area’s unique lens.

For example, if the course is Critical Reading and Writing, having students recognize “anti-Indianism” in literature would be one way to expose current laws, policies, and attitudes that stifle sovereignty, truth, and reconciliation. If the course is Foundations of Inquiry, using contested positions about the treatment of American Indians to develop the ability to judge the strength of arguments, would further pro-sovereignty support. If Leadership and Praxis, a brief study of Indigenous activism would be exemplary for students. For Organizational Theory, using the Indian Reorganization act to demonstrate awareness of the complex issues faced by managers in the area of ethics and social responsibility would be perfect. You get the idea.

(2) Identifying Colonial Hegemony in Each Course

Indigenizing a way of thinking or a practice requires recognizing problems with current thinking and practices. We cannot change that which we do not acknowledge as needing change. Together with students, faculty can discover what colonial assumptions are foundational and ongoing in the domain of the subject area. To get a sense of what this looks like, see Teaching Truly: A Curriculum to Indigenize Mainstream Education. It exposes hegemonic (colonizing) assumptions in English Language Arts, United States History, Mathematics, Economics, Science and Geography and shows how to replace it with a pre-colonized or Indigenous perspective and practice. Other references are easily found by Googling your course topic with the question “How is (fill in the course topic) influenced by colonized thinking, corporatism, or American hegemony?

A professor does not have to master this material in advance nor serve it on a plate to students. Such expertise or didactic approaches to teaching usually reflect colonized thinking. Indigenous learning is largely experiential. Of course, a great advantage exists in having an Indigenous teacher, especially one who was raised according to traditional values and is fluent in the traditional language. Even such individuals are likely to carry some colonized beliefs via their Western education. In any case, a traditionalist with a stronghold on original wisdom would mostly “teach” via guiding student research, observation, and praxis. Like any field of study, new knowledge and interdisciplinary investigation can unveil important precepts of the generalized Indigenous worldview and of unique, place-based Indigenous knowledge. Ample literature exists to assist the process of decolonizing education, but ultimately it is deep reflection, dialogue, and real-life applications that make the seeds of knowledge grow.

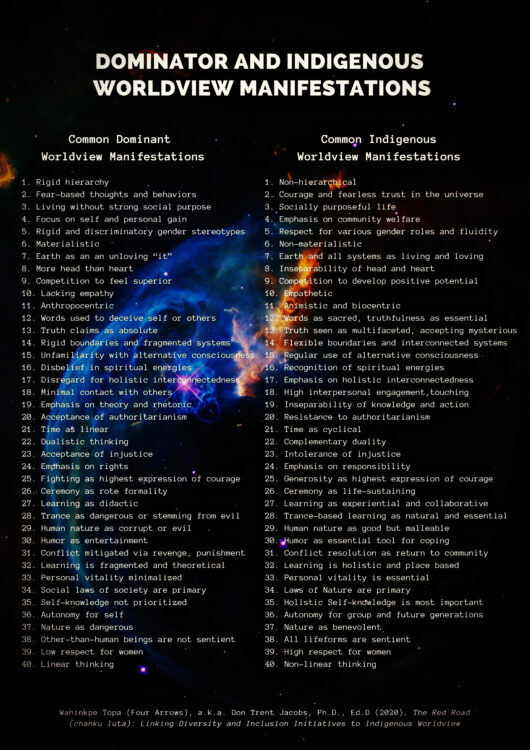

An excellent way to start the search for hegemony is to see the worldview chart here and talk with students about what parts of the course description or syllabus fall on one side or the other. Then study some basic ideas that are typically taught in the course the same way. What hidden colonial message operates? What harm does it do in the world? How can it be modified? With the faculty and the student joining in this process, equal footing during the discovery can bring forth the learning about the truly useful parts of the topic while exposing those that do not help prevent the world’s problems. It becomes an exciting adventure.

If a non-Indigenous instructor still feels nervous or unprepared to do this work, see my peer-reviewed article online from UBC’s Critical Education journal titled “The Indigenization Controversy.” It may help with rethinking this common apprehension or excuse for not moving forward with decolonizing curricula.

(3) Indigenizing Coursework

Working for Indigenous sovereignty will work best when coupled with an understanding of the advantages of Indigenization for all people. Giving First Nations back the freedom to control their education will happen faster when we realize the Indigenous worldview belongs to us all, and can offer solution to the existential crises facing life on Earth. It guided us for 99 percent of human history and, according to a large body of literature, did so without the kind of violence to ourselves and our planet. Many worldview comparison charts are available on the Internet that students and faculty can use for relevant discussion in each course. Such conversations can seek complementarity between the two worldviews or recognize areas where returning fully to an Indigenous precept about the world makes sense.

Decolonization and Indigenization are not just things to add to other “social/ecological justice” targets. They are intrinsic in the same way that any reference to social justice remains inseparable from ecological justice and sustainability. Ultimately, colonized thinking continues loss of human rights, rampant inequality, blatant racism or unconscious bias, hate crimes, and winner-take-all based violence. They are institutionalized in legal systems and education. Working within colonized systems that assume and support imperial, patriarchal nation-state, free-market capitalism, neo-liberalism, and hierarchical rule to obtain social/ecological justice is an impossible task. Although higher education generally reflects these same assumptions, it has the potential to originate a positive transformation.

Thus, we must ask two questions in every class: “What assumptions relating to the subject contribute to a better world and which ones reproduce or sustain practices that make it worse? This question applies whether or not the course is directly related to social/ecological justice. The second question is, “What alternative, Indigenous-based ways of thinking would be more likely to prevent such problems?”

(4) Making the Commitment

The fourth step must, of course, be the first step. Universities respond to having been pressured to start “Diversity and Inclusion” initiatives that give voice to marginalized students, offer programs that promote women’s rights and gender identity, and prevent racism and implicit bias. However, such programs fail to recognize that the opposite of exclusion is not inclusion, it is decolonization. Even with more and more rhetoric specifically about decolonizing higher education, it is rarely an “across the curricula” project. The lack of commitment of faculty, closely related to the lack of involvement of management, exists because, in essence, colleges and universities are fundamental tools of colonization. It is in the proverbial woodwork as much as it is the consciousness of most faculty and administrators in higher education. Of course, it is also in the consciousness of most students, even those who come to learn ways to change the colonized system.

The reason for lack of motivation and commitment to the decolonizing of higher education is that it is the default program. Rauna Kuokkanen addresses this in Reshaping the University: Responsibility, Indigenous Epistemes, and the Logic of the Gift (2010). She explains that the “Indigenous episteme” is marginalized, dismissed or invisible within universities. The most compassionate social/ecological justice educators inadvertently step on their toes by holding on to colonized values and precepts. One example believing in exchanging value for value as a given standard rather than “the logic of the gift,” an Indigenous worldview way that is profoundly different and involves an emphasis on generosity, non-hierarchical relationships, interdependence and responsibility for working in behalf of others, including non-humans, for its own sake. Again, regular referencing to a worldview comparison chart between the dominant and the Indigenous worldview can bring awareness and considerations about transformation to such differences.

So what might motivate commitment to decolonizing all curriculum in higher education? Certainly, the Coronavirus pandemic now upon us might give some incentive. However, well-intended administrators and faculty will have to recognize that standard educational practices themselves must change, and it may be unrealistic to think this will happen in most environments. Higher education’s efforts at governing and decision-making that emphasizes collaboration between administration and faculty have not historically been effective in making timely transformations. Too often, grand ideas suffer “death by committee.” This happens for a number of reasons, but one that the literature on it does not express relates to how the most even the most passionate social/ecological justice advocates bump into the unconscious colonized walls and pathways. The “new managerialism” phenomenon in higher education is part of this dilemma.

For these reasons, I propose that decolonizing the curriculum starts with the courageous autonomous commitment of individual faculty to follow the three steps above. If this can be accomplished in concert with collaboration, peer-review, or support from various others, it is all the better. Similarly, it can be helpful if the administration can implement a plan that allows for such faculty independence while finding ways to hold faculty responsible for the commitment. However, Indigenous worldview holds that the highest authority for action is honest reflection on lived experience with the deep understanding that all of life on Earth is intimately interconnected. This leads to autonomous, courageous decision-making that is always on behalf of community and the greater good. Hierarchical systems that do not reflect reverse dominance hierarchy usually obstruct more than they assist.

Below are 11 concepts and practices that reflect colonized thinking. These can be addressed in most any course.. If individual faculty realize the effect of colonized hegemony on what is happening in our world today, then perhaps with only the few ideas I offer here, more and more will come forward until the “hundredth monkey” causes a quantum leap. Progress (Never-ending growth, corporate control of life-support systems)

- Progress (Never-ending growth, corporate control of life-support systems)

2. “Winning “ (Uncooperative competition for self promotion)

3. Unlimited Wealth, Capitalism, materialism over life

4. Spiritual Separation from Nature and Interconnectedness

5. Disruption of Ritual and Ceremony

6. Childlike Dependence and lack of taking responsibility

7. Controlling Food, Water and the Air We Breath

8. Destruction of original language and cultures

9. Mysogony

10. The Assumption that Warfare is intrinsic to Human

11. Hierarchy and authoritarianism

12. Fear-based culture

13. Bias, conscious and unconscious

14. Inherent hegemony in a particular discipline/subject area

15. Inherent hegemony is educational processes

16. ACTUAL DECOLONIZATION (Truth, reconciliation, sovereignty of Indigenous People)