Purchase multiple sizes of this poster in our Society 6 shop here.

Kindred’s Worldview Poster by Four Arrows

Kindred World was founded on the values and beliefs of stewarding and protecting all life as interconnected, interdependent, and therefore, Kindred. Over the past quarter century, we have focused on creating sustainable, peace-loving humans through the integrated and interdisciplinary fields of science that support a life-affirming worldview, identified below in the Indigenous Worldview column. You can read more about our nonprofit’s history here, and discover how our many initiatives help ourselves and our culture make the shift from a Dominator Worldview to an Indigenous Worldview.

Please support our nonprofit work generously!

See below for download options, including PDFs, PNGs, and a black and white version for printing out.

Download your Worldview Chart poster or graphic below:

Kindred Worldview Chart Starry Night Background in PDF format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart Starry Night Background in PNG format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart in black and white for printing in PDF format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart in black and white for printing in PNG format: Download

About the Worldview Chart:

This chart is not intended as a rigid binary, but a true dichotomy best viewed as a continuum. It is meant to encourage seeking complementarity and dialogue. Absolutism is discouraged with the realization we are all participating in DW precepts to some degree. The chart assumes that all diverse cultures, religions, and philosophies can be grouped under one of the two worldviews. “Indigenous Worldview” does not belong to a race or group of people, but Indigenous cultures who still hold on to their traditional place-based knowledge are the wisdom keepers of this original Nature-based worldview. All people are indigenous to Earth and have the right and the responsibility to practice and teach the IW precepts. All have the responsibility to support Indigenous sovereignty, dignity, and use of traditional lands.

For non-Indians who are concerned about misappropriation, see the peer reviewed article,

“The Indigenization Controversy: For Whom By Whom.”

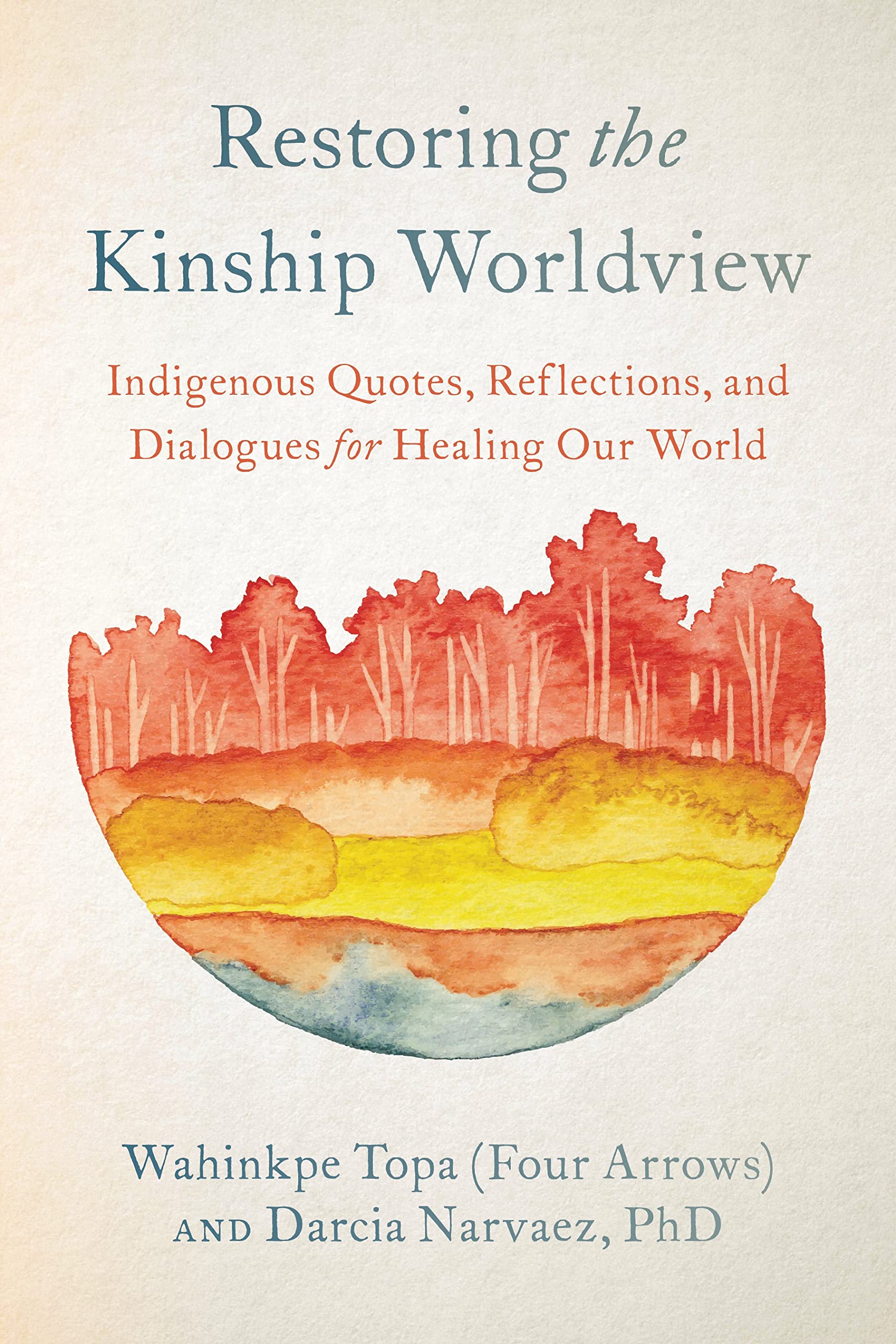

Worldview Chart and introduction by Wahinkpe Topa (Four Arrows), a.k.a. Don Trent Jacobs, Ph.D., Ed.D. Originally published in The Red Road (chanku luta): Linking Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives to Indigenous Worldview, 2020. Featured inRestoring the Kindship Worldview, 2022, by Four Arrows and Darcia Narvaez, Ph.D. Find Four Arrows and more on Indigenous Worldview at www.KindredMedia.org

Download your Worldview Chart poster or graphic below:

Kindred Worldview Chart Starry Night Background in PDF format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart Starry Night Background in PNG format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart in black and white for printing in PDF format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart in black and white for printing in PNG format: Download

Every Day Must Be Indigenous Peoples’ Day For Life To Continue On Earth

By Darcia Narvaez and Four Arrows

Go to the article and podcast on Kindred here.

Until relatively recently in human history, most people had a sense of a living Earth. We understood trees, forests, rivers, mountains, humans, animals and plants as living, sentient neighbors and community members. This worldview promoted an authentic concern for the mutual well-being of all. As can be seen among today’s Indigenous peoples who act to save the Amazon rainforest, humans evolved to be deeply connected, relationally and responsibly attuned to the natural world around them — otherwise they perished. In his book, Beyond Nature and Culture, anthropologist Philippe Descola documents the unique integration of culture and nature around the world in non-industrialized societies not overtaken by unfettered capitalism’s globalization.

We honor Indigenous traditional cultures and peoples with a commitment to reclaim this legacy and way of understanding our symbiotic relationships and interconnectedness as members of a sacred and living Earth. In light of the recent United Nations report on extinction rates that reveals how Indigenous worldview, not technology, is the key to rebalancing our ecological systems, such a commitment is crucial. What can we do to reclaim our original worldview? What can we do to help today’s Indigenous peoples with their struggles to protect their land, language and sovereignty?

Author and educator C.A. (Chet) Bowers describes how the industrialized world takes for granted several root metaphors that act like a straitjacket on thought and action. As anthropologist Marshall Sahlins pointed out, individualism, self-interest, linear progress, centrality and superiority of human beings, positivism (the need for an experiment to know anything), and belief in an insensate natural world are all considered strange by human societies around the world. All indicate a human orientation disconnected from grounding in the Earth.

Why do these notions seem logical to industrialized humans? Contemporary industrialized nations by and large undermine the development of human capacities, toxically stressing children and adults, leading to disconnection. Our research shows the importance of humanity’s evolved nest (Evolved Developmental Niche), which matches up with the high immaturity and needs of human children in the first years of life when neurobiological systems are shaped by social experience. The nest includes responsive calming care by multiple adults, years of on-request breastfeeding, frequent affectionate touch, extensive play, relational connection and social support. All these foster health and well-being, sociality, and morality through epigenetics and other plasticity effects in early life. Nature connection and ecological intelligence are part of our heritage as well, and are critical for sustainable living. But parents in industrialized nations are encouraged (and often forced) to deny babies and children what they evolved to need, establishing neurobiologically aberrant trajectories and long-term ill-being, dysregulation and disconnection.

Nature connection is apparent in all “non-civilized” groups around the world and was integral throughout the existence of our species. The fact that “civilized” humans, a type of society around for only 1 percent of the human genus’s existence, are disconnected from nature shows the unsustainability of civilization as we know it. As First Nation peoples know, disconnection is at the root of destructive acts.

As researchers, we lament how ignorant Western scholarship and media generally are about this nature-connected history. Humanity spent over 90 percent of its history as small-band, hunter-gatherer societies, living close to and cooperatively with one another and the Earth, with concern for future generations. Humanity would have died off without what we can refer to as our “Indigenous worldview.” As mentioned above, recent United Nations extinction rate report refers to the disregard for this worldview as the major reason for current ecological disasters, and notes that where the Indigenous worldview is operating today, thriving biodiversity is maintained.

Scholars routinely pick out or sort societies of the past in ways that make them look primitive or violent. They call any positive descriptions of our non-civilized history “romantic.” But the real romanticism is apparent in our unquestioning support for the path we are on, the one that assumes we can continue to extract from the Earth without penalty or limit.

Western science does not promote ecological attachment, though some come to the sciences from an enchantment with nature. Instead, Western science and scholarship encourage detachment and “objectivity” (relational disconnection) with what is studied. In either case, the ecological crisis cannot be solved by continuing intellectual discussions. Even Western scientists are coming to realize that to act responsibly toward the natural world, one must care about it in a relational manner, as Indigenous science and worldviewpromotes. One must feel and act connected to the Earth. Efforts to restore nature connection and “rewild” human nature are spreading. Awareness of and respect for the intelligence of animals, plants and insects are increasing.

Importantly, societies who hold an Indigenous worldview, including American Indian/Alaskan Native societies, have long prioritized “the seventh generation” and have done so with both heart and mind. Those who, against all odds, still hold onto this wisdom continue to put their lives on the line for future generations, as occurred with the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Humanity’s future depends on re-embracing the Indigenous worldview, its grounding in connectedness and its foundational love for all diversity. This a human heritage that we can restore and live out. We can revive a “common memory” of our species on the Earth and reshape the foundations of our governments and institutions, as U.S. Independent presidential candidate and member of the Navajo Nation Mark Charles advises. Charles, who identifies also a Christian, articulates a decolonizing agenda as necessary for relearning how to take care of our common home, Planet Earth, as Pope Francis has advocated. In fact, the recent Pan-Amazon Synod of Bishops in Rome, guided by Indigenous wisdom, not only acknowledges the church’s historical role in colonizing lands, peoples and cultures of the Amazon, it also refers to the imposition of Western culture onto Indigenous worldviews.

If we have come to a time when the Catholic Church — whose policies initiated the onslaught against our Indigenous way of being in the world — can now address decolonization and Indigenous worldview, perhaps we should make every day Indigenous Peoples’ Day. To remind us of who and where we are, we can begin to learn how to reclaim our more authentic worldview for education and survival.

Read more on media bias against Indigenous Worldview here.

Authored by :

Wahinkpe Topa (Four Arrows), AKA Don Trent Jacobs, is currently a professor in the School of Leadership Studies at Fielding Graduate University. A made-relative of the Oglala Medicine Horse Tiospaye, he served as director of education at Oglala Lakota College on Pine Ridge where he fulfilled his Sun Dance vows. Named one of 27 “visionaries in education” by the Alternative Education Resource Organization, and recipient of a Martin Springer Institute’s Moral Courage Award for his activism, he has authored/edited 20 books and numerous chapters/articles on Indigenous worldview.

« Back to Glossary Index

Comments are closed.