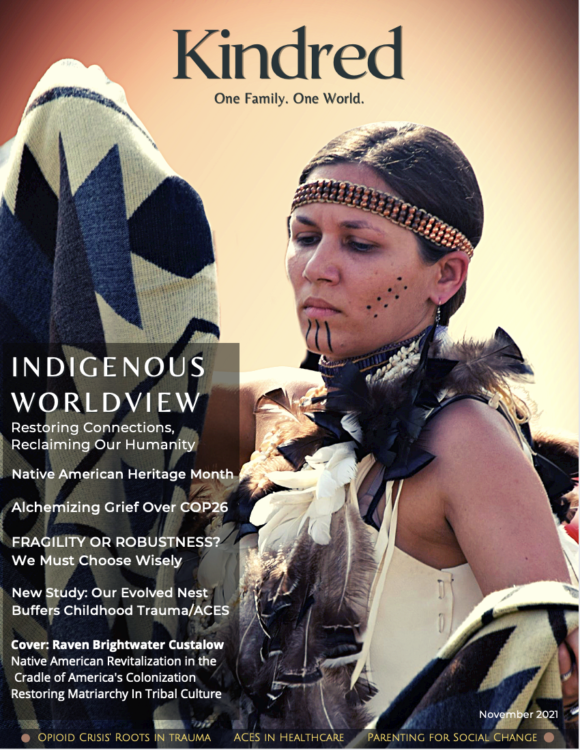

Revitalizing Indigenous Traditions In America’s Cradle of Colonization: An Interview With Raven Brightwater Custalow

Listen to Raven Brightwater Custalow and Lisa Reagan discuss the ongoing nonprofit work in Virginia to revitalize, reclaim, and decolonize Indigenous traditions in America’s Cradle of Colonization

About the Interview

Raven Brightwater Custalow talks with Lisa Reagan about her nonprofit work and expansive vision for revitalizing Indigenous traditions in collaboration with Virginia’s eleven Native American tribes. Raven shares her inspiration for her work, growing up on one of the oldest reservation in the country, and being surrounded by family members who practiced and taught Indigenous traditions in crafts and drumming. Raven’s work today includes a documentary series of the eleven tribes’ elders, ongoing presentations and educational programs, and collaborations with many tribal members. She speaks frankly in the interview about her frustration with some of the tribes exclusion of women in their leadership, a colonial remnant necessary for communicating with the patriarchal settlers 400 years ago. Raven talks of her hope of returning to the matriarchal roots of her tribal heritage, and preparing her young children to carry their Indigenous traditions into the future.

Visit the Eastern Woodland Revitalization on Facebook and on their website.

Revitalizing Indigenous Traditions In America’s Cradle of Colonization: An Interview With Raven Brightwater Custalow

EXCERPT FROM TRANSCRIPT BELOW

Sections of Interview (Click to Go To)

Meet Raven Brightwater Custalow

Revitalizing Native Traditions In America’s Cradle of Colonization

Education, Awareness, and Decolonization In Colonial Virginia?

Capturing Oral Histories Of Native Elders In Film

Decolonizing Tribal Patriarchy: Restoring Original Matriarchal Matrix

First Nation People Are Independent Nations: Who Governs?

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women: A National and Local Crisis

Meet Raven Brightwater Custalow

LISA: Welcome to Kindred. This is Lisa Reagan, and today I’m so delighted to be with Raven Brightwater Custalow who is going to talk to us about what is happening here in Virginia with Native tribes through multiple projects. Welcome, Raven.

RAVEN: Hello, my friends. My name is Raven. I come from the Mattaponi tribe. Thank you for having me here today and letting me speak with you all. Before I go any further though, I just want to acknowledge the land that I reside in, we call it Tsenacomoco, but we call it more commonly Virginia. The federal and state recognized tribes that have inhabited this land since beginning of time. I just want to acknowledge them: the Pamunkey, the Rappahannock, the Upper Mattaponi, the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Nansemond, the Monacan, Cheroenhaka Nottoway, the Nottoway of Virginia, the Patawomeck, and the Mattaponi.

And I just want to give honor to the ancestors of those people, their current tribal citizens and future generations, as we’ve overcome over 400 years of discrimination, assimilation of oppression, and genocide. So, thank you for having me here today, and I’m excited to speak with you all.

LISA: Thank you so much, Raven, for coming. I too am here, not very far from you, down the road in Toano, Virginia which is listed in the county’s oral history book as Algonquian for “high ground.” My family acknowledges we live on ancestral Powhatan tribal lands. What called you to this work that you have begun in Virginia?

RAVEN: In my day job, I’m a nurse practitioner, for about three years now. I’ve provided health care down in the rural Northern Neck area, in Virginia. But I remember, as a little girl, you know, you dream of what you want to be when you grow up. And I remember telling my cousin I wanted to be a baby doctor one day and I didn’t really know what that meant or what that all entailed. But throughout my education and college, I decided to go into nursing school. And then I was like, “You know what? I really do want to provide healthcare.” I’ve always wanted to provide healthcare to my people. So, going back to become a nurse practitioner was a way that I could do that. I’m really excited to say that tomorrow I start my new job at a new Indian health service clinic that was opened up by one of my sister tribes recently.

So, I was finally able to accomplish that dream that I set for myself, but really, when it comes to the cultural work that I do, that really came from growing up on the Mattaponi reservation, one of the oldest reservations in the country, established in 1658. I grew up with my family, with my culture surrounding me. My grandmother is a tribal matriarch, well known for her pottery and bead work. She was a big influence on me and to my sister and cousins. And then my dad, he had his own drum group and went all over the country drumming at powwows. So I had those influences culturally that inspired me to continue that on. I’d say now that I’m a mother, I have two children, a five-year-old daughter and a four-month-old son, and that drove me even more to be more active in cultural preservation because they are going to be our future and they’re going to be what keeps us here, keeps us going, keeps our culture strong.

And so, I feel a responsibility to learn myself and then to teach that to them and to the other young ones so that they can continue that work as they grow up.

Revitalizing Native Traditions In America’s Cradle of Colonization

LISA: So you are involved with a number of projects here in Virginia and one of them is the Eastern Woodlands Revitalization Project. Can you tell me a little bit about that project’s vision?

RAVEN: Yeah, so me, my sister, and my husband, a few years ago, we really felt like we needed something in our area where all of our tribal nations could come together and learn cultural practices that are specific to our own people. A lot of times, especially if you go to like powwows, which are kind of like a festival that the public is welcome to, it’s very mainstream. There are different styles of dance, but they’re not necessarily indigenous to us. It’s Virginia Native people. There’s been a lot of practices and traditions that have been lost or not practiced as much in the recent years. And we felt like we needed something to help bring that back. And so, we decided we’re just going to go ahead and we’re going to start this nonprofit and we’ll, we’ll see how it goes.

Before the COVID pandemic, we were having classes once a month, mainly on the Mattaponi reservation, but then we started to visit each of the tribes around us and bring a class to their tribal centers – before the COVID pandemic. We had great turnout, from young children to elders. It has been a big learning experience for me too. But you know, I’m excited that we can say we’re still trying to do to do these things, even with the limitations that the pandemic has given us. We haven’t been able to meet together as much as we want to, but we’re continuing on, and I hope it continues to grow and become stronger every year.

LISA: What has been the response both from the tribal members who are participating in the Eastern Woodland revitalization gatherings and then from the public?

RAVEN: The people that attended, I think they like it because they keep coming back and we’ve had some tribes reach out to us recently to try to come back to their tribal centers now that they’re open with some safeguards in place, of course, for health reasons. But to come to their centers and hold some of these classes. I have a couple of classes scheduled the next year with one of the tribes. So, I think it’s a welcome thing among the communities because we want to see our traditions specific to who we are as Virginia people. We want to see that grow and we want to be able to share that with others so that people understand who we are as Virginia First People, a little bit better.

So, I think that’s been a big acceptance among the community members. We would set up a booth to try to get our name out there and let them know what we were doing. And we’ve had a great response and we’ve met a lot of awesome people, people who work in these different sectors, um, non-profit work, language work, environmental work. So, some collaborative things, maybe in the future that we could do together. We’ve received donations from the public to help us sponsor this work because, before we got our 501C3, we didn’t have any funding outside of our own pockets, what we could donate ourselves for these classes. So with our 501C3, now we’re eligible to start applying for grants and whatnot. So that will be a help for funding purposes. But yeah, I think it’s been well accepted both among tribal community and just the general public as well.

Education, Awareness, and Decolonization In Colonial Virginia?

LISA: Where we are located here in Virginia is a hotspot for where a lot of elementary school books for decades have told the “story of America” as being the story of colonization, with not much of a mention of the histories of Native peoples and their stories. It seems like it could be quite a task to approach this very embedded history when you’re in the middle of what is called the “Historic Triangle of Virginia and America” – Jamestown, Yorktown, Colonial Williamsburg. This area is one of the top ten international hotspots for tourists. Can you speak to where we are and doing this work in that context?

RAVEN: I don’t think a lot of people realize how many Native communities and Native tribes there are in Virginia. There are 11 total, federally and state recognized tribes. Virginia has a rich history of indigenous culture and a lot of people don’t even realize that. I think back to going to school, I think maybe in fourth grade they touched on the different tribes. And that was just one of the SOL questions we needed to know is, how many tribes that were in Virginia at that time? And that was pretty much it, in terms of education about the tribal nations here. But there really is a rich history and the complexities of that history and how it’s evolved over time. We were among the first people to come in contact with English settlers over 400 years ago.

And the fact that we are still here and still very present in the communities is an amazing thing, because we did have to overcome genocide purposely through wars. And then also through disease, there was the Paper Genocide not that long ago through Walter Plecker who tried to change the documents of who we were, saying we are no longer indigenous people, to take that away from us. Just having to face assimilation, the loss of language, spiritual practices and cultural practices. The fact that we’re still here and I would say we’re thriving, we’re doing this work to revitalize and reclaim some of those things that were lost is really an amazing thing.

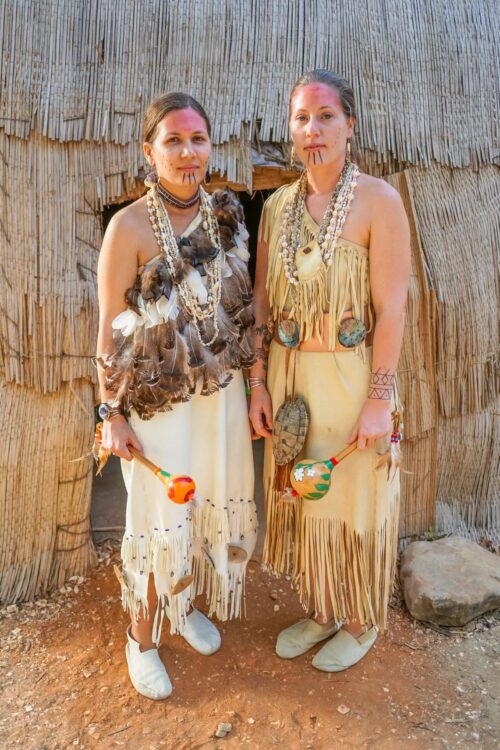

Williamsburg does have a lot of areas that talk about the native peoples of Virginia, now. And I think there’s been a push, in Colonial Williamsburg and Jamestown, to really tell those stories, factual stories of the Native people that were here, and the interactions they had with the English settlers. I’ve been glad to see that work just in the Williamsburg area. Actually, my husband works for Colonial Williamsburg and the American Indian initiative. And he gets to do stage performances once a week or so. And they get to tell, actual, true stories about the interactions between Native people and the English and the outcomes of those and the effects that had on our people. So, yeah. Our history is rich here in Virginia. We’re still here. And hopefully in the school systems will start to come on board and work with the tribes to tell true history, so that it’s taught throughout, throughout all the schools.

Capturing Oral Histories Of Native Elders In Film

LISA: You have a film series that is in process right now and you’re documenting elders of the different tribes in Virginia and their stories.

RAVEN: Probably a year ago, someone sent me this link to this grant and said that I should apply for it. And I was like, okay, let’s see what happens? I’m always looking for a new project and new opportunity when it comes to cultural work. It was through an organization called Dance Place. They’re located in Washington, DC. And they they’re a dance center and they provide classes to the public in that area, but there is a push to recognize the Indigenous people of Virginia, especially around the DC, Maryland, Virginia area, because they are the people that they serve. I wrote this grant and it was mainly about capturing oral history and tradition on film for the tribes, but then also making a short documentary about what, what they were sharing with me.

So that’s in process right now and it’s been inspirational. Most of the people talking, they are elders, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be elders. It’s really up to the tribes. I let them know what we’re doing and let them decide, do you want to be a part of this? And who do you want to represent you? Most of them have gone back to their council and talked about it and decided on the people they want it to represent them in these films. Um, so I hope they, they found that useful, the ones that have completed it. We did one for Upper Mattaponi tribe on their community garden and they had a community planting day and we went there and filmed that and they actually have it up on their tribal website, I believe. It’s just been really cool and awesome to be able to meet some people that maybe I hadn’t known from these other tribes and get to hear their stories and the things that they’re working on. It has been really a great opportunity.

LISA: I got to see the one with your father talking about the shad. I really enjoyed his, uh, his instruction on how his ancestors didn’t have watches and clocks, so when this plant bloomed, we knew it was about time for the shad to start running in the river. I just loved that his story.

RAVEN: Yeah. And those are the things that need to be captured and told and retold so that we don’t forget that because that’s something that can be lost very easily, that knowledge; it’s just one little piece of knowledge, but it has a big impact on our ability to shad fish. That if anything, that’s what I wanted to be able to capture in these films, is something that will never be forgotten. And, and it’s just another way of preserving, a piece of our culture.

Decolonizing Tribal Patriarchy: Restoring Original Matriarchal Matrix

LISA: So, Raven, your work is so much about preservation and revitalization and education, but it seems like there’s also an evolution of thought happening within the tribes themselves. Some of what you’ve been involved with lately has to do with the patriarchy of the tribes and trying to introduce the concepts of women as leaders. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

RAVEN: We have Eastern Woodland people and that encompasses several tribes up and down the east coast. A majority of us are a matriarchal matrix, lineal societies, meaning, you when people get married, you come from your mother’s blood lineage and that’s the tribe that you come from. But then the fact that women are held to a high regard, a high standard, and for us civically, women were the land workers, we kept the home. The land was, if you could say it was anybody’s, it was the women’s land, it was a women’s home. And the men would come – when two people got married – the men would come and live with the women. So that’s a different concept when it comes to patriarchy, because the man that holds the land is the man that owns the home.

So, that’s a different concept. English settlers came over here and saw that and didn’t understand why that was. We had women leaders, women chiefs throughout time. But when you think about patriarchy and the English settlers, they did not want to interact with women in the government. They didn’t think that was a woman’s place. So over time you see this adoption of patriarchy in our tribal communities, and now it became a standard in some of the tribes. I’m not going to speak for every tribe because there’s many tribes that have very powerful, very knowledgeable women that are sitting in these council seats, sitting as chief. But I will say, for my tribe specifically, we are having a hard time overcoming that patriarchy concept that was imposed on us through assimilation. Understand, for survival reasons, at a certain time period, maybe that was needed so that we could still be here today.

But we are coming up on the year 2022 and our women currently do not have voting rights. We don’t have the right to run for council seats. We don’t have the right to run to become chief. We technically cannot call for a lot of land on the reservation. These are all laws in the current law book. There’s been a push in our community to say, “This is not right. This is not who we are as Native people. This is not traditional. This is not what our ancestors would have wanted. We need to change.” We’re having some conflict and some, some difficulties overcoming this, but I’m hoping in the coming weeks or months that change will happen, because it is long overdue.

First Nation People Are Independent Nations: Who Governs?

This is a basic civil rights that women should not be discriminated against. So that’s what we’re working on now is how can we include our women to be equal to our men in our community? Because we need both men and women to work together so that we are still here 400 years after today. We made it this far, but if we don’t get our women back in there, we are the childbearers, we are the cultural keepers, we are the ones doing this cultural work to keep it alive and keep it in our communities. If we keep excluding our women, we’re not going to be the medicine of people anymore. We’ll eventually disappear into history.

– Raven Brightwater Custalow

LISA: So, help our listeners understand, tribal government is not regulated by the United States, or individual states or federal guidelines of any kind. So those would not apply to the tribal government deciding to exclude women. Is that correct?

RAVEN: Right. So tribal nations, but particularly the federally recognized tribes, are sovereign nations. We’re seen as our own nation. If you’re recognized by the federal government and you’re your own nation, if you’re a state recognized tribe, you’re seen as your own nation through the state, and therefore we have the ability to create our own laws and things like that. This a self-determination act that helped solidify that fact that, we’re our own people. We should be regulating our own government. However, there’s some conflict if a tribal government takes away some basic civil rights of their own people, and there has to be some regulation in that piece of it. The Indian Civil Rights Act, became a law in 1968. That said tribal governments cannot pass or enforce laws that violate certain individual rights.

This is a basic civil rights that women should not be discriminated against. So that’s what we’re working on now is how can we include our women to be equal to our men in our community? Because we need both men and women to work together so that we are still here 400 years after today. We made it this far, but if we don’t get our women back in there, we are the childbearers, we are the cultural keepers, we are the ones doing this cultural work to keep it alive and keep it in our communities. If we keep excluding our women, we’re not going to be the medicine of people anymore. We’ll eventually disappear into history. So, hopefully we can get to that point of bringing back what our ancestors already knew: that our women are important, very important, to our tribes and to our future. Hopefully, we’ll see some change here soon.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women: A National and Local Crisis

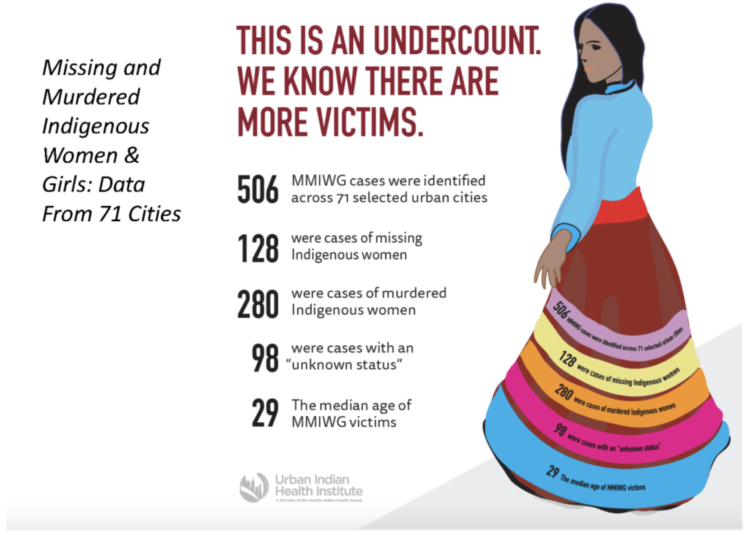

LISA: So it’s decolonization that is still happening within the tribe itself from 400 years. Wow. Well, I see on your Facebook page, you have signs with you standing with some of the women holding up the murdered and missing Indigenous women statistics. This is a national concern right now and crisis. Can you speak to that? What is happening, um, in your advocacy in that project?

RAVEN: Missing and murdered Indigenous women is a big movement among Indian country, but also to becoming known to, not just America, but to the world. Native Indigenous women have the highest rates of murder, kidnap, and rape. We really have to ask, why is that? Why, why are Indigenous women being targeted in that way? And how can we stop it? That’s the big movement that’s been going on and just bringing awareness to that. I believe that those photos were taken at one of the local pow-wows by one of our friend, who does a lot of photography work, had this vision of doing, of doing this kind of series, where she would, take pictures of us holding these signs, just to help bring awareness to that movement and to that cause. A lot of people don’t know that our women are targeted in that way. There are the ramifications it has in our community when our women are being taken, or going missing, thousands of thousands of women. I would encourage everyone to just go and just Google it MIW and, and just, just read the statistics. It’s mind blowing.

LISA: Is there anything else that you would like for our listeners to know about you and your work? We’re at the end of our hour together, but this has just been so fantastic and I’m so deeply inspired by everything that you’re doing and taking on Raven. Thank you so much, but what else would you like for us to know?

RAVEN: I have this question asked to me by someone the other day, about how to approach us, how to ask this question, what is appropriate, what is not appropriate? I would just say, just remember, we are people; we are human. We live in these spaces with you. You probably know someone that has an indigenous background, but maybe they don’t talk about it a lot. But we are in these spaces where we’re in your workplaces. We do a lot of the same things that you do. And when it comes to our culture, as long as you’re coming to us with respect and with good intentions, that’s all we want. And if you don’t know something or have a question, I just say, just ask. I don’t think that anyone would be offended by a question you need clarification on.

Now if our answer doesn’t sit well with you, that’s okay. But just don’t take away from our experience as Indigenous people, because there’s a lot that has affected us; every time it continues to affect us, just through colonization. So yeah, I would just say, we’re here with you. We’re in this world with you. We welcome you to just have conversation with us. I mean, that’s all we really, really want. So yeah, I think that’s my main thing.