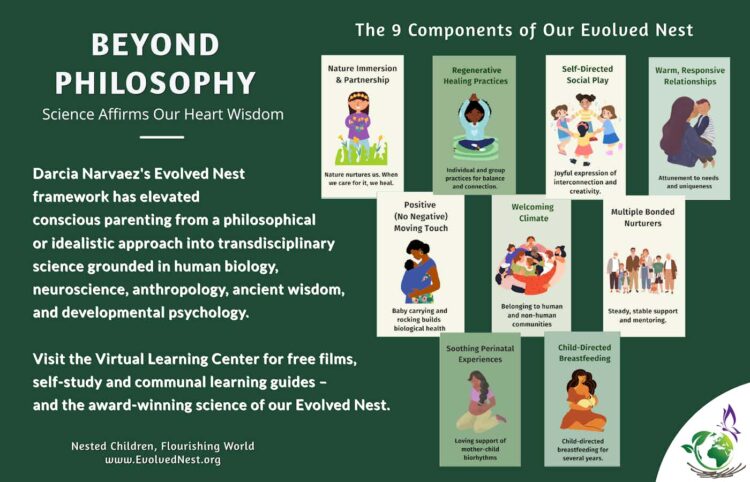

Evolved nestedness in early life has the perfume of enchantment. Multiple nurturers accompany baby, providing ongoing support as needed with evolved nest practices that represent love in action for our species. Mothers are fully supported. Joyful presence accompanies baby, nearly always in arms. Comforting is instantaneous. Nestedness shapes a biology of love and enchantment with the world.

As the child becomes mobile, the community allows the child the freedom to choose their actions. They understand that the years before age seven to be ones of hypnotic imitation, and so they are careful in what they expose the child to.

When the evolved nest is not provided to babies and young children, they grow up in a frightening, disenchanting world, their desires desiccated. Unnestedness shapes a biology of fear in the child’s body, undermining their potential.

How do individuals construct meaning?

Meaning making starts at the beginning of life. In early life nestedness, it is developmental ubuntu: I become what we are together. The pattern of feelings is united, connected. If you are empathic towards me, I will be empathic towards you all. I am good, the world is good, we are good together. The baby is in charge of their growth, nurturers attentive to meeting their nonverbally-signaled needs with evolved nest practices.

Meaning making starts at the beginning of life. In early life nestedness, it is developmental ubuntu: I become what we are together. The pattern of feelings is united, connected. If you are empathic towards me, I will be empathic towards you all. I am good, the world is good, we are good together. The baby is in charge of their growth, nurturers attentive to meeting their nonverbally-signaled needs with evolved nest practices.

The trajectory is set for virtue development because nestedness means that needs are being met as they arise and biological and psychological systems are co-regulated. Co-regulation by nurturers shapes the child’s systems to be able to eventually self-regulate, independent of others but tuned into Earth’s resonance. The child is grounded in self-security, self-confidence and joyful creativity. In our ancestral context, this would occur by around age 5. A neurobiologically-rooted narrative of goodness is carried in the body-mind-spirit of the child.

Early life unnestedness takes a different pathway. There is inconsistent, unreliable, even rare, ‘us togetherness.’ Togetherness might be painful from disregard, or even from punishment. The dominant pattern of feeling is of disconnection, despair and pain: you are cruel to me. The child feels that cruelty and pain are normal human experiences. I am bad, the world is bad, and we are bad separately. The trajectory is set for vicious development because unnestedness means needs are not being met as they arise, disturbing the equilibrium in the child, affecting the rapid growth scheduled in early life. The result is potentially dysregulation of all kinds (neurotransmitter, endocrine, emotion systems, impulse control, digestion/immune system, and much more). Primary feelings will be of insecurity, self-doubt and even numbness. Independent self-regulation does not develop appropriately so the person will need external regulators to feel okay (e.g., drugs, a dominator belief system) and to regulate the now cultivated dysregulation.

Notice how these neurobiological narratives are based in embodied personal experience. Personal experience sets up attractors, energy biases, that draw one to particular emotion blobs/sets in terms of rhetoric, justification, relationships, and action. Having felt the injustice of unnestedness in early life, I am drawn to perceive similar injustices in the world. I will also be drawn to feelings of resentment, looking for someone, something to blame. It won’t be my parents, because that is too risky—I must rely on them. But I could blame myself, especially if told frequently how bad I am in religious texts and events. Thus, personal experience of feeling bad is hooked up with verbal justification for it (you are evil). The world becomes black and white, and full of threats.

Notice how these neurobiological narratives are based in embodied personal experience. Personal experience sets up attractors, energy biases, that draw one to particular emotion blobs/sets in terms of rhetoric, justification, relationships, and action. Having felt the injustice of unnestedness in early life, I am drawn to perceive similar injustices in the world. I will also be drawn to feelings of resentment, looking for someone, something to blame. It won’t be my parents, because that is too risky—I must rely on them. But I could blame myself, especially if told frequently how bad I am in religious texts and events. Thus, personal experience of feeling bad is hooked up with verbal justification for it (you are evil). The world becomes black and white, and full of threats.

The unnested world gets very narrow. Instead of ongoing contentment of needs being met through nestedness with the flow of serotonin and diverse connection, I am rewarded only with small moments of pleasure that stimulate dopamine (hits)—a sugary drink that mimics the sweetness of breastmilk, the eye contact and smile of my carer that offers crumbs to my true self, screen entertainment that interprets my feelings of alienation, being tossed in the air for a sense of embodiment or even spankings as a recourse for my deep need for touch. Moments of seeming responsiveness. Never content, I endlessly yearn and look for those intermittent rewards. I don’t expect relaxed contentment, since it was rarely experienced, but reside in ongoing withdrawn numbness.

It’s also possible that I give up socially. I instead get obsessed with objects. They are more predictable and less threatening. Filling my room, my home with things that keep my attention, searching for more, keeps me from feeling the deep despair I carry. You can see how the modern-industrialized-capitalist world is built on unnestedness, making everyone anxious, competitive hungry ghosts.

These contrasting deep worldviews were identified by Sylvan Tomkins as ideo-affective postures. The humanistic view of ‘the world is good and so are we’ is trusting and unfearful of human nature. The normative view, ‘the world is bad and so are we,’ is distrustful of humanity and seeks to control others.

Tomkins noted that parenting fosters one or the other, nurturing or harsh. Indeed, but I would say now that the key is nestedness or unnestedness, which puts the onus on the community.

To re-spirit humanity and reverse humanity’s current pathway towards mutual and ecological destruction, we must restore our nestedness and our sense of goodness through awakening to Earth’s sentience and to the spirit of the Cosmos. Apply to our Nesting Ambassador Program to learn how to help self and others.

References

Narvaez, D. (2011). The ethics of neurobiological narratives [SLIGHTLY REVISED]. Poetics Today, 32(1): 81-106. ORIGINAL https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-1188194

Narvaez, D. (2014). Neurobiology and the development of human morality: Evolution, culture and wisdom. Norton.

Narvaez, D. (2025). Overcoming climate havoc with inner development from deep nestedness. Ecopsychology, 17(3), 201-215. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2024.006

Tomkins, S. (1965). Affect and the psychology of knowledge. In S.S. Tomkins & C.E. Izard (Eds.), Affect, cognition, and personality. New York: Springer.

Tomkins, S. (1965). The psychology of being right-and-left. Trans-action, 3(1), 23-27.