Cultivating Emotional Intelligence In Your Child: The Five Rites of Passage PART ONE

Above: “Children want to give love as well as receive love,” says Kate White, APPPAH director of education in the video below. “To give and receive love is a rite of passage that develops the core belief, ‘My whole being is lovable and I can love with my whole being.’ This core belief is one of the foundations for lifelong emotional intelligence.”

Watch the new video with Robin Grille and Kate White below, Human Neurobiology and Emotional Intelligence: The Five Rites of Passage.

Read more about emotional intelligence in part one of Robin Grille’s three part series, also below. Read Part Two here and Part Three here.

About the Video, Human Neurobiology and Emotional Intelligence: The Five Rites of Passage

Kate White, director of education for the Association for Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health, APPPAH, talks with Robin Grille, Australian psychologist and author of Parenting for a Peaceful World, about the five rites of passage humans face at conception, in utero, at birth, and as infants through age seven. These rites of passage present themselves as basic, neurological needs that, when met, translate into core beliefs that support lifelong, emotional intelligence. The five rites of passage and resulting core beliefs are:

1. The Right to Exist = “I belong here. It is safe to be me.”

2. The Right to Need = “Life nourishes me.”

3. The Right to Have Support = “It is okay, and not shameful, to ask for help.”

4. The Right to Freedom = “I have the right to be autonomous, to make my own decisions.”

5. The Right to Love = “I can love with my whole being and be loved for my whole being.”

Learn more about the rites of passage to emotional intelligence in Robin Grille’s three part series below. You can also read about the five rites of passage in Robin’s book, Parenting for a Peaceful World.

This interview was filmed by Kindred as a part of Robin Grille’s Parenting for a Peaceful World USA Tour in December 2013.

Cultivating your Child’s Emotional Intelligence: The Five Rites of Passage

Part One of a Three Part Series. Read Part Two here and Part Three here.

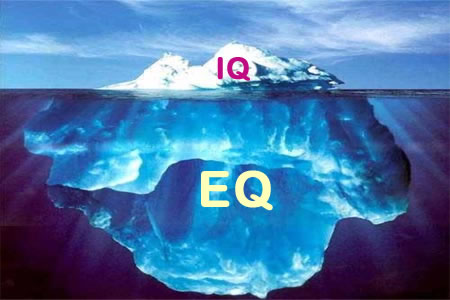

Since the turn of the 20th century, the importance of “intelligence” (quantified as “IQ” – intelligence quotient) has been over-emphasized in almost every aspect of human endeavor.

Indeed, IQ has been popularized to such an extent that parenting and educational methods are geared to maximizing children’s intellectual abilities. An entire industry, supported by reams of literature, has sprung up around sophisticated methods of IQ measurement, interpretation of IQ test results, and hence the mapping of children’s career futures. Few people have been spared the indignities of being subjected to an IQ test at some point in their lives.

Indeed, IQ has been popularized to such an extent that parenting and educational methods are geared to maximizing children’s intellectual abilities. An entire industry, supported by reams of literature, has sprung up around sophisticated methods of IQ measurement, interpretation of IQ test results, and hence the mapping of children’s career futures. Few people have been spared the indignities of being subjected to an IQ test at some point in their lives.

The beginning of this IQ fetish can be traced back to the Age of Reason in 17th and 18th century Europe, when leading philosophers began to promote “rational” thought as the path to human perfection. This trend has since culminated in today’s post-industrial era, when we have come to worship at the altar of “intelligence” – the supposed panacea for the world’s ills.

Thanks to the meticulous and exhaustive observations of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896-1980), we know much about the way a child’s capacity for rational thought matures and how cognitive development is linked to the functions of reason, logic, memory and language structures. Unfortunately, the importance of the cognitive faculties has been grossly over-emphasized, at the expense of wisdom about the dimension of feelings.

Consider this: In January 2000, Time Magazine voted Albert Einstein the “Person of the Century”. While his achievements are certainly formidable, they have not touched anything essential to human happiness. Why do we prize brains above the heart and soul? The fact that a high IQ has often been found to correlate with depression says little for its adaptive advantages. What’s more, IQ is a poor predictor of success in relationships, and has nothing at all to do with general life satisfaction or physical and psychological health. One of the saddest and most common misconceptions of our times is that a high IQ leads to emotional balance and psychological maturity.

Our intellect-driven culture stresses the need to teach children how to think, reason and perceive. We are new and unsteady beginners in our efforts to teach children how to feel, how to create, and how to navigate successfully the choppy waters of human relations.

However, you may be glad to know that after a long love affair with the IQ, the honeymoon is just about over. Finally, it has been recognized that intelligence, just like money, cannot ensure happiness. Interest in children’s emotional development is gaining in popularity and has gained renewed attention from psychologists.

“Emotional Intelligence”, a term coined by Howard Gardner in Frames of Mind (1983), describes a domain of human consciousness that has, until recently, been seriously neglected. The study of emotional intelligence and how to nurture it in our children is undoubtedly the next frontier in social evolution. It is currently enjoying an explosion of academic attention, with Amazon.com already listing over 50 titles that deal with the subject. Even mainstream schools are starting to move away from teaching methods based solely on competition and intellectual development, opting instead for a more cooperative approach to developing children’s emotional aptitudes.

Nowadays there are also efforts by psychologists and educators to define the concept of emotional intelligence; to devise instruments for measuring it in individuals (EQ); and to teach its properties to both children and adults alike. It has finally been acknowledged that EQ is more important than IQ when it comes to “people skills” – success in career, in personal and business relationships, and in raising fulfilled children. The abilities to recognize, manage, and appropriately express one’s own feelings have little to do with intellectual functioning, but are more vital to our well-being and overall success in life. Emotional intelligence is what determines the way we cope with painful change, disappointment, stress or adversity. An undeveloped EQ can ruin work prospects, undermine relationships and contribute to all sorts of addictions in even the brightest people.

Nowadays there are also efforts by psychologists and educators to define the concept of emotional intelligence; to devise instruments for measuring it in individuals (EQ); and to teach its properties to both children and adults alike. It has finally been acknowledged that EQ is more important than IQ when it comes to “people skills” – success in career, in personal and business relationships, and in raising fulfilled children. The abilities to recognize, manage, and appropriately express one’s own feelings have little to do with intellectual functioning, but are more vital to our well-being and overall success in life. Emotional intelligence is what determines the way we cope with painful change, disappointment, stress or adversity. An undeveloped EQ can ruin work prospects, undermine relationships and contribute to all sorts of addictions in even the brightest people.

Emotional intelligence includes, among a host of other things, the ability to deeply empathize with others, to lead wisely or follow with grace, to honor our limits as well as celebrate and fulfill our talents and to give and receive love and support. Relationships cannot be truly intimate, nor can they grow, without a deep sharing of our emotional inner worlds. Most of us have learned early in our lives to hide or ignore our feelings, to believe that they aren’t important, and that is why relationships can become stunted and dull. More pertinently, our ability to inspire and impart emotional intelligence to our children rests on our own mastery of feelings and our willingness to learn and grow in this area.

In one way or another, we are all struggling to refine, develop, and expand our emotional and relationship skills. Life, with its pain and joys, could be considered a “big school” for the emotions.

Any committed relationship, whether it be business or personal, requires a great deal of emotional intelligence – not just to stay “together”, but to remain alive and dynamic. Although most of us can claim to be “fine” or “OK” most of the time, few remember how to feel deeply, how to experience bliss or joy.

Following are some questions you might ponder to gain insight into your own emotional terrain and to understand more clearly what is meant by “emotional intelligence”. Please remember that this is not a quiz; EQ is not quantifiable. When it comes to emotional intelligence, we are all on a voyage of discovery! These questions are designed to provoke reflection about areas of your emotionality, that you might like to expand or develop. Some of the questions may seem a little banal at first glance, nevertheless, do take the time to consider how each item applies to you personally.

Relationship Faculties

- If you are sad, grieving or mourning, do you allow yourself to weep? Do you allow others to see your tears?

- Can you express anger freely and non-destructively, then let it go?

- Do you quickly let go of grudges and resentment?

- When you are afraid, do you let trusted others see your fear?

- Do you let yourself know that you are afraid?

- Do you take notice of your emotional and interpersonal needs, and express these needs assertively? Respectfully?

- Are you able to recognize when you need help, then ask for help or support?

- Can you receive help, as well as give it?

- Can you say “no” without feeling guilty?

- Can you strongly protest against mistreatment?

- Can you make decisions without feeling easily taken advantage of?

- Do you easily express, as well as receive, tenderness, love, passion?

- Can you enjoy your own company, yet gladly and comfortably accept intimacy?

- Do you listen clearly to yourself, and to others?

- Can you empathize with the needs and feelings of others, without judgment or criticism?

- Can you accurately perceive what others are feeling, and feel compassion for them?

- Can you motivate others without resorting to fear tactics or manipulation?

Emotional Fluency

- Do you allow yourself to frequently experience and enjoy pleasure?

- Do you allow yourself to experience bliss, ecstasy, excitement, fascination, awe?

- Do you often laugh out loud – a deep belly laugh?

- Do you sometimes feel moved by the courage or the spirit of others?

- Can you contain (rather than repress) your impulses and delay your gratification, without resorting to guilt, shame, or suppression of your emotions?

Flexibility and Balance

- Can you focus your energy on work, yet balance this with fun and rest?

- Can you accept and even enjoy others who have different needs and world views?

- Do you let yourself be spontaneous, play like a child, be silly?

- Are your goals realistic, and does your patience allow you to work towards them steadily?

Self-Esteem

- Can you forgive yourself your mistakes, and take yourself lightly?

- Can you accept your own shortcomings, without feeling ashamed, and remain excited about learning and growing?

- Do you respect your strengths and vulnerabilities, rather than inflate with pride or fester with shame?

- Would you say you are generally true to yourself without blindly rebelling or conforming to social expectations?

- Can you bear disappointment or frustration, without succumbing to criticism of self or others?

- Are you kind to yourself, or hard and even punishing?

- Can you self-motivate?

- Can you gracefully accept defeat and failure and still feel OK about yourself?

You may even like to ask significant people in your life how they see you in terms of these questions. Your areas for potential growth are signaled by those questions you answered in the negative.

Our unfamiliarity with emotional intelligence means that we will continue to suffer, on a large scale, from social ills arising from emotional disability and injury. In Australia, poor emotional and relationship skills are directly to blame for some of the highest rates of depression, youth suicide, and problem gambling in the world. A deficiency in emotional resources is the basis for our epidemics of eating disorders, substance addictions, and bullying in the playground or work environment. Consumer greed and gullibility to seductive advertising are driven by a massive lack of emotional fulfillment. Our fledgling emotional resources leave us floundering in stagnant or dull relationships, or hurting from broken partnerships and shattered families.

Fortunately, unlike IQ, emotional intelligence can be learned and expanded throughout life. Goleman (1995) speaks of nourishing parent-child interactions as the essential building-blocks of emotional intelligence. We build our emotional structures by imitating our parents, and through our responses to the way in which we were brought up. In his book, Building Healthy Minds (1999), Stanley Greenspan M.D. states that what we learn about relationships and emotions in our early childhood years – when our central nervous system is growing most rapidly – is “engraved” into our neural pathways. As with the learning of languages, new emotional competencies can be acquired later in life, though with considerably more effort. The absorption rate is highest in early childhood, and it is for this reason that, as parents, we have both the opportunity and the responsibility of most significantly affecting our children’s EQ.

Most people can bring children up into functional adulthood, but we all fall short in one way or another when it comes to providing the optimal environment for our children’s emotional development. It is very difficult to give them what has not been given to us, and hence we are restricted by the insufficiencies of our own childhood, and by the limited credence and support that our community gives to the realm of feelings.

For some time now, psychologists from various schools of thought have been trying to trace the way in which emotions develop in children, much the same as Piaget defined the stages of cognitive growth. A guide map describing precisely how emotional intelligence unfolds can be extremely useful in helping us to promote and facilitate emotional fluency in our children. In the following pages, I intend to summarize the psychological and emotional needs specific to each of the five stages of early childhood psycho-emotional development. By implication, each stage requires a different set of conditions, and a specific approach to caring, if the emotionality of the child is to flourish. I recognize that none of us can consistently provide these conditions at any stage because we are limited as parents, humans, and as a community. A yardstick of what is ideal is not to be used for self-criticism but as a directional marker, since parenting also entails a growth process and developmental journey for the parent.

The development of our core, characteristic emotional make-up is set down in layers over roughly the first seven years of life. Patterns established here aren’t necessarily set in stone; however, emotional learning is most powerful at this time due to a child’s exquisite openness and vulnerability. When a child’s basic emotional needs are met at each stage, the foundation is laid for emotionally intelligent responses that will be automatic and spontaneous later in life. On the other hand, the acquisition of new relationship skills and emotional competencies in adulthood can often be an arduous process, triggered by painful situations.

The five childhood rites of passage that I wish to describe are rooted in biological changes, and are therefore universal and not generally subject to cultural nuances. Each stage finds the child trying to master (with our help) a specific developmental task and emotional function which will prepare the ground for self-image and later relationships. It is during the first rite of passage that the child establishes, at his or her deepest, core level, a sense of self-worth and value for life itself.

First Rite of Passage: The Right to Exist

What is happening: This developmental stage spans the second trimester in the womb, through birth, and the first six months of life. Recent research published in the Journal of Perinatal Research and The Secret Life of the Unborn Child(Thomas Verny, 1994) demonstrates that the fetus is surprisingly aware of, and responsive to, its mother’s feelings, as well as to a range of stimuli in the nearby environment, such as bright lights, loud noises, music and even the quality and tone of other people’s voices. From within the womb – before an awareness of “self” has emerged – the fetus is profoundly affected by the emotional environment surrounding it, since it is constantly linked to maternal mood states and attitudes via hormonal ebbs and flows. The fetus responds to stress with visible signs of agitation, while settling peacefully in response to favorable emotional climates. How the parents feel about him sends ripples through the baby’s primitive consciousness – he records and senses their joy at his coming, or ambivalence or even hostility to his presence. Neither the fetus nor the neonate have a capacity for boundary formation: mother, environment and self are one, with no differentiation. Consequently, the baby is highly absorbent of parental emotions; he feels and becomes identified with what the parents are feeling, about themselves and about him. In this innocent and permeable state the baby registers how his parents feel toward him as the very nature of his own being, and begins to form around this experience his deepest attitudes to himself, and to human life.

At birth, and for months afterwards, the baby is extremely vulnerable, and so aloneness or lack of human warmth can bring about the deepest of terrors and despair. The imposition of regimented feeding and sleeping routines is experienced by the baby as a shattering break from her own natural inner rhythms.

Optimal developmental experience: The ideal situation is one in which both parents long for the child from a position of organic, emotional and financial preparedness. Both parents are sufficiently emotionally fulfilled and ready to give and love selflessly, and are able to pleasurably meet the enormous demands of the helpless infant. Ideally, help is at hand from a supportive family and community (it does take a village!) when the parents are otherwise occupied or feeling exhausted.

Non-traumatic birth is free of emergency or defensive obstetrics, which the acutely sensitive newborn experiences as violence and shock. Unfortunately, modern labor ward birthing methods focus on emergency measures while severely ignoring the emotional and psychological needs (and fragility) of both mother and child. The unnecessary physical separation of mother and baby soon after birth constitutes a brutal discontinuity from the intimate contact of the womb. The transition into the outside world is critical in giving the baby information about the nature of the environment he has entered. Therefore, his arrival needs to be extremely gentle and sensitive, into a warm, holding and non-violent world where the child will be joyously welcomed (see Frederick Leboyer’s Birth Without Violence, 1995). The parent’s joy at receiving the baby is the essential ingredient of his spiritual nourishment. Ideally, baby and mother need to remain constantly physically together in order to foster bonding and healthy attachment. A warm, soft, supportive and constant holding bathes the baby in feelings of contentment and security, which orient her toward emotional balance and well-being. Both mother and infant require protection from conflict or intense disharmony during this fragile time.

Loving eye contact and tender vocalization satiate the baby’s hunger for human sustenance, and provide a subconscious reference for loving and empathic relationships later. It is vitally important, around the dawn of life, that the child’s few and simple physical and emotional needs be met on his terms, according to his own organic rhythms, rather than according to the parent’s (and society’s) needs for routine, peace and quiet, etc.

Millions of years of evolution have fine-tuned the human organism in such a way that a baby’s cry always signals the need for some kind of attention. The emotional equanimity and vitality of the baby rests in the parents’ responsiveness to these needs. The baby thrives best in constant physical contact (carried in a sling during the day, co-sleeping at night). Liedloff (The Continuum Concept, 1975) aptly refers to this period as the “in-arms phase”. The last thing a baby needs is a separate bedroom! Such is the pace of transition, which we have evolved to biologically and psychologically require, from one-ness with mother’s (and after birth, also father’s) body to gradual and gentle separation.

Developmental Task: The most primal emotional competencies are learned earliest in life. The way our passage through this stage unfolds imprints upon the basic sense that: “I have the right to be here” and that “I am welcome in the world”. The emotional cornerstone of inner security is positioned at this time, as are the basic building blocks of healthy self-assertion and of trust in one’s own feelings. The right conditions engender deep feelings of belonging and of being intrinsically connected to community and Nature.

The main wounding experience: A baby’s natural experience of pleasurable and blissful connectedness is sabotaged by schedule-based rearing methods. Enforced and imposed routines disconnect the baby from her organic, natural rhythms long before she is ready for self-containment and bring about an early interruption to the flow of feeling. Parental non-responsiveness, cold or mechanical handling, insufficient holding or frequent abandonment, are all shocks to the crystalline sensitivity of the baby. An insensitive, rough or violent environment is experienced by the baby as utterly shattering and even annihilating.

Regrettably, our culture – backed by mainstream pediatrics – has tended to deny the emotional acuity and receptivity of infants under two, which has given rise to their tragic isolation in bassinets, cribs, and playpens, and the disregarding of their cries for touch and nurturing. Deep feelings of alienation, separateness, unworthiness and even hostility can result from these earliest and most primal needs not being met, feelings which, even when masked much later by superficial functionality, manifest in disturbances of relationships or intimacy.

Emotional Function and Core Beliefs: Some core beliefs arising from injurious experiences during this stage include: “I don’t belong”, “I am worthless or loathsome”, “Life is dangerous or terrifying”, “I am alone in the world”.

Some core beliefs arising from a positive experience at this stage are: “It is safe to be me”, “I belong here”, “I have the right to be here”, “I have the right to show the way I feel”, “It is safe and OK to feel my feelings”, “I can accept conflict as part of life”, “Life is essentially safe and nurturing”. A healthful passage through this stage enables people to feel secure, connected to their feelings, practical and realistic. Thinking and feeling remain in harmony with each other, rather than becoming opposed and separate faculties. The opportunity exists here to prepare the groundwork for a strong, core sense of Self.

Potential Adult Manifestation of Injury: Withdrawal is the only psychic defense available to the baby at this time, and therefore shocks experienced here can lead to a demeanor of remoteness or aloofness. The movement is away from contactual relationship with others, toward excessive intellectualization; a state of analytical detachment from life, or a tendency to reverie. The adult becomes uneasy in the unpredictable world of feelings and emotion, and therefore over-emphasizes the “reasonable”, the “rational”, the “logical” – or the “abstract” and the “philosophical”. A fragile countenance or hyper-sensitivity to hurts and slights are also legacies of wounding during the first rite of passage.

This is part one of a three part series. Read Part Two here and Part Three here.

Photo: Shutterstock/Evgeny Atamanenko