The Dangers Of Refusing To Answer The Call Of The Hero’s Journey

Dear Kindred Reader,

I am honored to be included in Kindred Media and Community’s nonprofit educational series on Parenting As A Hero’s Journey. It is wonderful to be a part of Lisa Reagan’s terrific work in support of parents who realize not only how important it is to care for our children well, but also that it is very hard, and we all need as much help as we can get.

I am blessed to be the father of three emerging adults, two by my blood and one by virtue of having taken on another epic, though common, challenge—a blended family wherein I met my youngest, now twenty-two, when he was nine. My own, main credential is 30 years of being a parent. My feeling of privilege in being a part of this series is that this is a group that understands that the biggest challenge of parenting is not our children but ourselves. We are better parents to the extent to which we are willing and able to face that fact and work on ourselves. I call it “parenting as emotional healing,” and the great myth of the hero’s journey most definitely applies.

In this essay, and the accompanying podcasts, webinar and email nuggets, I will do three things. First, I will briefly summarize the hero’s journey; perhaps I should use shero, or s/hero, but I am using the term hero for simplicity’s sake and to be consistent with the ancient telling—hero is intended as a gender-neutral term, and obviously in general women do a great deal more parenting than men. Next, I will address the danger of refusing the call to be heroic, and will present three areas in which that regularly occurs in our modern society—drugs, education and technology. Finally, I will present a few of the gems, referred to in this series as wisdom nuggets, that have been particularly helpful to keep me on course.

— John Breeding, PhD, author of The Wildest Colts Make The Best Horses

The Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey is an age-old mythology. In 1949, Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces was published. This remarkable book documents the fact that cultures throughout our planet’s geography and history tell a story of the hero, a story with universal similarities. It is what Campbell refers to as a monomyth, a story that reveals profound truths about human nature. All of us are called at times in our lives to face some great challenge, usually seen or felt in both our inner and outer worlds. The hero is one who answers this call and undertakes the arduous hero’s journey. The truths of this journey are as relevant for each of us today as they ever were in any ancient culture.

Withdrawal-Initiation-Return: this is the hero’s journey. As with, for example, Hades yanking Persephone by the ankle into the underworld, we are forced to withdraw from outer world demands and go through an intense initiatory ordeal before we are allowed to return and use the gifts we have gained for the good of our community. One of my books is called The Necessity of Madness and Unproductivity. In our society, an overwhelming value is placed on productivity, and “madness” is anxiously suppressed, mostly with drugs. Hence, the space for withdrawal and initiation is minimal at best—doubly so when you have children, as any parent can attest! Yet unproductivity is exactly what is necessary to undergo a hero’s journey, or in plain speech to take a step back and look at yourself, and do a little inner work. Unproductivity is necessary to step out of the rules of productivity and move into personal transformation.

What about madness? Carolyn Myss, medical intuitive and best-selling author, begins her tape series, Energy Anatomy, with the provocative assertion that madness is an absolutely essential stage in the attainment of spiritual maturity. The reason for this has to do with the fact that we are all necessarily, inevitably and thoroughly initiated into the beliefs of our tribe, or culture, from the time of our conception onwards. These beliefs thoroughly impregnate our body and our psyche, largely at a non-verbal level. We are all tribal members, loyal to tribal law, way before we even begin to approach the idea, much less the experience, of becoming an individual.

When we question and contradict the beliefs and values of our family of origin, for example—the ways we were parented—and decide to do it differently, we are betraying our tribe and that is judged as “madness.” It is also often experienced as madness in that we go through periods of anxiety or depression in the face of our uncertainty and insecurity. When we take a close look and realize that our parents did nor really see us in some ways, or treat us very well, we may be left with the troubling feeling that we ourselves were betrayed. Madness and unproductivity are necessary ingredients of deep change, yet they are discouraged and often punished in our society, very often with labels and psychiatric drugs.

Another writer, P W Martin, amplifies Joseph Campbell’s teachings through the works of Carl Jung, T.S. Eliot, and Arnold Toynbee. Martin makes this transformational journey very real for anyone who cares to undertake the arduous task of self-realization today. These two works, by Martin and Myss, are useful to consider our true nature, especially as it applies to the process of personal transformation in general, and to parenting in particular. I will use their teaching to illustrate a little of the journey below.

“The hero is the waker of his own soul.” – Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces

This teaching is about responsibility. Most of us are confused about responsibility, conditioned to feel it as a burden and a source of guilt and pressure. I believe this is because our parents and teachers were themselves conditioned to believe in a view of human nature as flawed, defective, sinful, irresponsible. If we view children as naturally irresponsible, our job becomes that of teaching them to be, making them, responsible. This attitude leads inevitably to efforts to control and shape the target of our concern, to guilt, shame, pressure. This is, in fact, one of the most frequent concerns I hear from parents. How do I teach, get my child to be, “make them,” responsible?

Psychology and education tend to answer this question by supporting the basic position of this last question; various subtle or not-so-subtle versions of behavior modification (reward and punishment) are offered. This validates the underlying assumption of children as naturally irresponsible, similar to the way a yes or no answer to the question “Is my child ADD?” validates the erroneous assumption that there is such a “mental illness” as ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder). Instead, I respond first by probing the question and leading the parent to consider that there is no need to “make” their child responsible. The child, as all humans, already is responsible. It’s her inherent nature.

I often demonstrate this with two arguments, both of which involve looking at young children. The first point comes from what we know about the effects of child abuse. A child who is abused inevitably carries a heavy load of guilt and shame that comes from the certainty that “If I am abused, I must be bad. It is my fault (responsibility) and I deserve it.”

Children naturally conceive of themselves as responsible centers of the universe, when abused, they take responsibility for it. This point is well understood by anyone who has worked on healing early traumas and explored the depths of their own conditioning; those who do not know themselves at that level often have difficulty comprehending this truth. They may, if they have observed young children, still be able to consider my second point, which is simply that little ones absolutely love to help out and be given responsibility. They delight in it and are so enthusiastic. We are born responsible. It is our nature.

We do not need to “make” our children responsible. We do need to provide appropriate opportunities and guidance for how to express responsibility at different levels as they learn to master themselves and the outer world. For the interested reader, I discuss this issue at greater length in my book, The Wildest Colts Make The Best Horses.

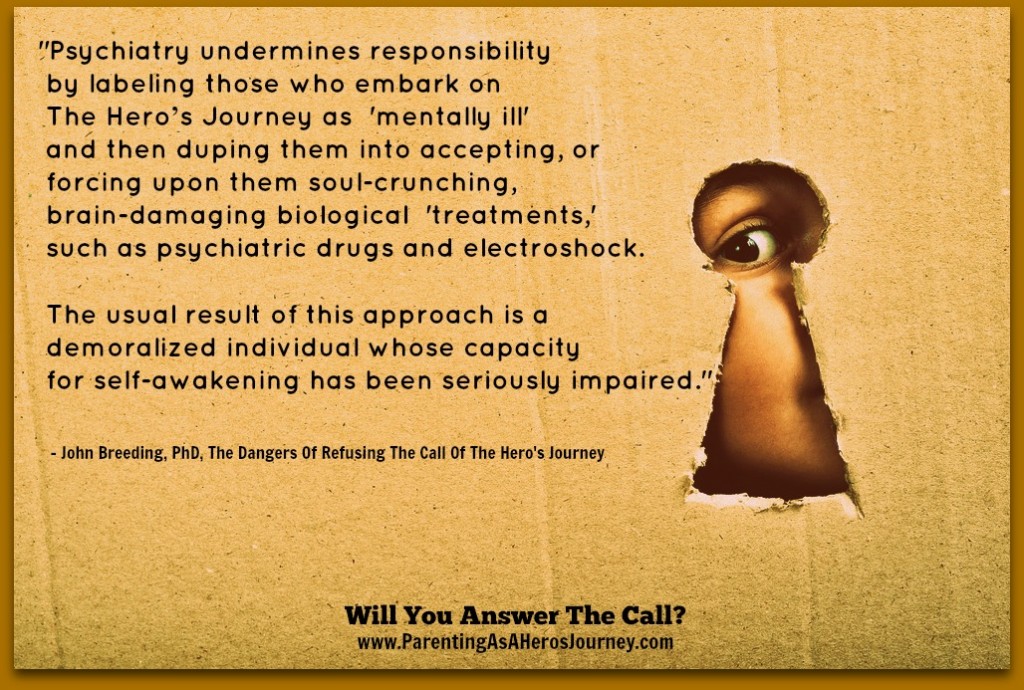

Psychiatry undermines responsibility by labeling those who embark on the hero’s journey as “mentally ill” and then duping them into accepting, or forcing upon them soul-crunching, brain-damaging biological “treatments,” such as psychiatric drugs and electroshock. The usual result of this approach is a demoralized individual whose capacity for self-awakening has been seriously impaired. Genuine support respects and encourages the truth that no psychiatric authority can do for others what they must do for themselves, that when it comes to transformation, everyone is her or his own authority. In the words of George Bernard Shaw, “Only those who have helped themselves know how to help others and to respect their right to help themselves.”

“The first stage in the process is the realization that ‘there is something wrong about us as we naturally stand.’ Without this realization, nothing happens.” — William James

Generally speaking, as long as we are comfortable and happy with where we “naturally stand,” we will tend not to undergo the rigors of transformation. False pride and the need to avoid self-examination can be an obstacle; until we experience humility we will resist change. Simply put, the teaching is that we are motivated to change mostly through frustration and dissatisfaction. The thought or feeling that there is “something wrong about us” is a catalyst for growth. Psychiatry calls it a “symptom,” and by “diagnosis” and “treatment” enforces an understanding of this as literal, concrete evidence of defective biology or genetics. Genuine support responds with appreciation and encouragement for the discontent that signals the beginning of the self-renewal process.

“The first work of the hero is to retreat from the world scene of secondary effects to those causal zones of the psyche where the difficulties really reside.” – Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces

The conventional unwisdom being what it is, my perspective is that retreat from the world scene truly can be a heroic act. Retreat is a betrayal of our society’s prime value, namely productivity. For example, we still tend to follow the fast-food school of grief where one is encouraged to get over it in a weekend and get back to graduate school. The truth is more like in fairy tales where the widower covers himself in animal skins and ashes, and lives in a hollow tree for seven years.

The conventional unwisdom being what it is, my perspective is that retreat from the world scene truly can be a heroic act. Retreat is a betrayal of our society’s prime value, namely productivity. For example, we still tend to follow the fast-food school of grief where one is encouraged to get over it in a weekend and get back to graduate school. The truth is more like in fairy tales where the widower covers himself in animal skins and ashes, and lives in a hollow tree for seven years.

Psychiatry is more and more geared to support society’s demand that people should and need to be always working. Not only do people on the “journey” not work, but they consume much less. None of this is good for the business of psychiatry or the economy. What would the effect of “withdrawal” on a large scale have on the stock market? A large part of the work life of corporate America is boring, repetitious, not at all inspiring and purposeful to those who do the work. The ubiquitous use of coffee to get going and the coffee breaks to keep going are essential to the enterprise. And now we give stimulant drugs to millions of our school children as well. It seems to me the rat race is getting rattier.

What would happen if America decided to face its addiction to stimulants, and the workers gave up coffee? Slowing down means having space and time to think, ask questions, explore your life. This is dangerous and threatening to the demands of an economy based on incessant “growth” and productivity. And it feels very scary to those who keep their own inner demons and dragons at bay by constant activity.

To quote Wes Nisker, a writer for the Buddhist journal Inquiring Mind, “Slowing down in this culture may be the most difficult tantric exercise ever conceived. Mindfulness may be the ultimate speed bump.”

I realize this must sound like a discouraging Alice in Wonderland pipe dream to people in the throes of intensive parenting—hence the basic, fundamental truth that parenting is hard not because we are dong anything wrong, but because of the harsh reality that our society is not set up to support parents and families—I call it parental oppression. So my goal is to call forward compassion for ourselves as parents. I do think that on a small ongoing scale, we must find ways to slow it down and to step back and do a little inner work. Many of the teachers in this series have methods for doing this. I will offer one below in the section on parenting as emotional healing.

“There are those who go searching for an artesian well and come instead upon a volcano.” P.W. Martin, Experiment in Depth: A Study of the Work of Jung, Eliot and Toynbee

Many of us are moved by inspirational writings or sermons that tell us of the beauty and glory of God’s kingdom, of the joy of “walking in the Light.” Perhaps we get an experience, a glimpse of greater love and joy, and we naturally want more. So we become seekers, and we tentatively follow the teachings to go within, that the kingdom is within. And we look for the light, and we fall into dark places inside of ourselves. One client of mine tells me that she lived for ten years in what she calls “the cleft in the rock,” experiencing joyous connection with the spirit, through Jesus, in her prayers and meditations.

Her life circumstances changed, and she fell into what she calls her “bloody pit.” Suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalizations, drugs galore, and electroshock followed in the next two years. She found me years ago and has done enormous, intense personal work; it has been a profound ordeal. Her life remains challenging, but on a most definite upward trend. She is now beginning to feel that spiritual connection again.

There are many others, of course, who come upon a volcano without any searching. Regrettably, many of us, including myself, have come upon that volcano in the context of parenting. It s tragic to me, for example, to see a new trend of pregnant and new moms taking antidepressants (Breeding & Philo, 2011). The point is that great difficulties do, indeed, reside in the deep zones of the psyche.

Psychiatry has abandoned these very zones from which comes its name; Psyche means soul; a psychiatrist is by root definition, if not in practice, a doctor of the soul. Instead, they favor a belief that life experiences calling for a “time out,” a period for reconsidering one’s place in the world and the meaning of life, are the result of a biological defect. Genuine support for someone going through a transitional period can only come from those who know and respect the opportunities and risks inherent in this process, have confidence that positive growth can result, and stand ready to help if help is wanted.

“The parent is in the role of Holdfast; the hero’s artful solution of the task amounts to a slaying of the dragon. The tests imposed are difficult beyond measure. They seem to represent an absolute refusal, on the part of the parent ogre, to permit life to go its way; nevertheless when a fit candidate appears, no task in the world is beyond his skill.” – Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces

Just as a basic teaching about dreams is that we are not only our dream ego, but all the characters in the dream, so we are not only the hero in our parenting journey, but play all the parts at various times. Holdfast is the archetype of the parent or any entity whose prime directive is to maintain the status quo. According to Holdfast, resistance is pathological and cooperation is insight. Genuine support, however, validates the individual’s struggle for self-realization always and in all ways, even when he or she challenges society’s core beliefs and practices, so long as in doing so the rights of others are not violated.

“The returning hero, to complete his adventure, must survive the impact of the world.” – Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces

Just as withdrawal and inner work are fraught with peril, so is the return. Newborn growth and awareness carries with it a great vulnerability, and our society can be harsh. Those who are satisfied with their place in the social order perceive the returning hero as a threat. If the hero is right, they must be wrong. And if they’re wrong it follows they should change. And that is when the sparks begin to fly because people don’t like change. It may be the product of eons of conditioning, just plain inertia, or a combination of both, but people will do just about anything rather than undergo a change, especially one that involves self-examination. To paraphrase the great philosopher and writer, Hermann Hesse, for most people, nothing is more distasteful than taking the path that leads to oneself.

The presence in the community of a hero, a self-evolved individual, has that kind of effect on people. Psychiatry plays the role of keeping out or removing individuals who are shaking us up. If they are able to return to the community after being labeled and treated by psychiatrists, they return as damaged goods, unlikely to frighten or inspire others about the need to change. Genuine support entails easing the way of the hero upon his or her return. This might mean offering moral support, camaraderie, material assistance, or political protection (e.g., just be known as having some local friends can help prevent private or governmental sanctions). And if one is unable or unwilling to help, then the important thing is to stay out of the way.

“The deeds of the hero in the second part of his personal cycle will be proportionate to the depth of his descent during the first.” – Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces

“Madness” is necessary for the process of transformation, necessary in order to become spiritually mature. This quote further emphasizes that the “descent” is not only valuable to the individual, but also a treasure to the community. Many believe that “dropping out” of external work is dangerous because they profoundly distrust human nature. Genuine support starts with an understanding that it is part of our nature to be responsible and to be of service to others. There are times, however, when because of unresolved problems or owing to the dictates of a higher imperative, inner work is the priority. Respectful, above all respectful, and compassionate attention and assistance can be crucial to the individual so engaged, and can lead ultimately to important benefits to the community once this phase of the renewal process has been completed.

Refusing the Call

The idea is that we are called to do the hero’s journey. Very occasionally, the call is epic and has all the drama and flavor of the ancient myths. More often it is not so dramatic, but even then the basic model of withdrawal and return applies. I think that sometimes the intensity of the ordeal is proportional to the extent to which we have, consciously or not, resisted the process of stepping back, and taking the time and the responsibility to face ourselves and do some inner work. In the dedication to my book, The Wildest Colts Make the Best Horses, I wrote:

To my children, Eric and Vanessa, for the intense demand of their spirited natures which has forced me, kicking and screaming to transform myself and my life in ways I could never have imagined, again and again and again. . .

I have learned that, when I get triggered, I either face myself and work on it, or suppress my children. In this section, I will take a short look at three institutional forces that play the role of Holdfast, suppressing our young people, and creating, promoting or allowing opportunities for parents to refuse the call to parenting as a hero’s journey.

Education

There are a number of great writers on the subject of education as a suppressor of children’s true nature; my own favorites are John Taylor Gatto, John Holt and Chris Mercogliano. The main idea for me is that children are inherently brilliant, imaginative, zestful self-directed learners, and that the schooling system works as an institutional force to dampen their spirit and render them more submissive and obedient. I will just briefly refer to three aspects of the educational system as illustrative.

One, the environment is set up mostly as a competitive enterprise, consistent with our society’s claim to virtue about the great goodness of competition.

Two, young people are often put under extreme pressure that is quite detrimental to learning, joy and well-being. Parents all too often get caught up in this as they become worried about their children “falling behind” and such nonsense. Coming from a place of fear, we parents then all too easily get caught up in further machinations that actually make things worse, such as the third institution of biopychiatry that I address below.

Third, it seems that schools have moved more deeply of late into a posture of “zero tolerance,” another face of fear, and one that echoes a general trend in our society, which may be construed as part of that general disastrous epic called the war on terror. In any event, what it means is rather than young people enjoying the attention of relaxed, thoughtful adults who help them when they are having a hard time, the response tends to be police-like, harsh and punitive.

To stand back and allow this, even worse to actively collaborate or support this kind of attitude and behavior toward children is to refuse the call to be a hero and face your discomfort around challenging school authorities, or your fear of emotion, or failure, or judgment, or your internalized feelings of hopelessness or powerlessness. The hero’s journey is a call to face both outer authorities and inner demons and dragons, and dealing with our education systems is one that no parent can avoid, without paying a very heavy toll.

Technology

We are no doubt in uncharted waters regarding technology whose role in our lives, and our children’s lives, is incredible. It did not take long from the advent of television for thoughtful adults such as Jerry Mander with his Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, to send out warnings about the dangers and deleterious effects of TV. Since then, the uncharted waters have become tsunami waves of screen time for humans, most definitely washing over the lives of our precious children with not only TV, but all kinds of computer, video games and telephone screens.

As a society we are clearly refusing that call to be heroes and protect our children, especially our young children. As individual parents, this is another huge place where we are called to defend the natural adventure of life and resist the pseudo or virtual experiences that are offered as entertaining, stimulating, yet pathetic substitutes. As a counselor, I have too often seen what happens when parents yield to the convenience and quiet that comes from allowing children to sit in front of a TV or video game or other electronic screens, and thus refuse the call to set strong, proper limits on screen time for their children.

The consequences of this short-term benefit typically show up when the parents realize that their child is avoiding responsibilities missing social and outdoor experience and play, isolating from the family and such, and decide they need to intervene. Such efforts to curtail their child’s screen time are usually met with resistance and sometimes the parents end up feeling like they have “created a monster.” I have seen occasions when it really was horrific, ending in violence. More often it is a lesser form of conflict and unpleasantness, but the outlines of a hero’s journey are always present as there is a necessary withdrawal from the “productive” activities of life into an initiatory struggle involving all kinds of emotional and relational ordeals. For those who endure and survive, the return to the natural adventures of family life and living is a gift.

Biopsychiatry

Biological psychiatry, biopsychiatry for short, is the model that drives our mental health system. The theory is quite simple, and goes something like this:

- Failures in adjustment (a child’s problems in school, for example) are due to mental illness.

- Mental illness (such as ADHD) is due to a biological (chemical imbalance theory) and/or genetic defect (bad gene theory).

- Therefore, biological treatment (drugs).

The theory can be expanded, but that is the gist, which provides the claims to virtue that justify using toxic and addictive drugs to control children’s behavior by calling it the prescription of medicine to treat an illness. To offer just one illustration, parents who resist stimulant drugs for their children who medical or educational authorities want to label ADHD are made to feel guilty with statements like, “If your child had diabetes, you would give them insulin wouldn’t you?” The end result is that millions upon millions of our children and adolescents are taking powerful psychiatric drugs, many of them taking a few or several at once. I have written extensively on this topic, much of which is available on my website at www.wildestcolts.com.

One recent article describes some of the many difficulties in working with an adolescent boy on a pharmacological cocktail (Breeding, 2015) Just three of these difficulties are the fact that being on psychiatric drugs tends to suppress emotional expression, undermine responsibility of all involved, and add an array of complications related to drug effects and withdrawal. As a hero’s journey requires free expression, a high level of responsibility, and all of one’s wits, I hope this provides a small glimpse of the problem.

Here is a last glimpse into this terrible domain, a brief decoding of the three-part theory of biopsychiatry presented just above:

- Failures in adjustment are multicausal. Sometimes it is because there are inherent problems when one is asked to adjust to a situation that is oppressive to our true nature. See the topic of education as one of our three examples of institutional forces of Holdfast.

- Mental illness is a metaphor. As hard as it is for many to accept, no problem routinely seen by psychiatry has been scientifically demonstrated to be of biological or genetic origin. That is why there is no objective test or indicator for any so-called mental illness, including, for example, the ubiquitous ADHD. “Mental illnesses” are diagnosed strictly based on behavior, and, simply put, behavior is not a disease.

- Psychiatric drugs are toxic and addictive, and have a wide range of deleterious effects. For example, the stimulant drugs such as Ritalin and Adderall typically used on our children, controlling for dosage and form of administration, have an effects profile virtually identical to methamphetamine (crystal speed) and cocaine. Psychiatry calls it medicine for mental illness. I call it poisoning our precious children.

Parenting as Emotional Healing

The hero’s journey begins when we are yanked into the underworld of the deep psyche, and parenting definitely has an ordeal aspect in this regard. A wide array of our children’s behaviors can be excellent triggers for unresolved feelings of hurt, fear, shame or anger. Disrespect, disobedience, defiance, aggression, whining, crying, lying, almost anything that somehow touches a place where we were hurt as children can be such a trigger. Many of the teachers in this series have methods they recommend to help, and here is a simple formula I find useful as a way to begin working with this idea of parenting as emotional healing; K. Lavonne, author of Tomorrow’s Children, taught it to me.

Step 1) Recognize that you are out of your loving with your child. This does not mean out of your permissiveness, but out of your loving and neutrality; it means that you are emotionally triggered. This usually looks like either an urge to punish or to give up and withdraw. It generally means that you are not able to think well about your child, and have forgotten that they are doing the best they can, and that their “bad” behavior is an effort to get your attention on a place where they have some distress and need your help.

Step 2) Ask yourself, “Who am I in this situation?” This means exploring your internal state when you are triggered. It might be, “I’m an angry woman who wants to throttle my child.” Or “I feel like a hopeless, defeated little boy who just wants to curl up and disappear.” It might be one of those humbling situations where you recognize, with a sinking feeling, that the precise words that just came out of your mouth were those of your own mother’s, in just her tone of voice: words you had promised never to use with your child.

Step 3) Ask yourself what behavior or quality in your child are you reacting to. Perhaps you can’t stand his whining or her defiance, or lying.

Step 4) Ask yourself how you are in relationship to this quality inside of yourself. This is the inner work of self-discovery and emotional healing. One place to work on this is in the area of lying. The work of personal transformation requires great honesty; my friend, Brad Blanton, has a bestselling book called Radical Honesty: How To Transform Your Life By Telling The Truth. His whole premise is that your personal growth is limited only by your incapacity or unwillingness to be honest. He says that we’re all liars, and getting honest is a big work for all of us. The great task of parenting is to do our own work because we can effectively help our children only in areas where we are relatively free of distress. If your child has trouble making friends, and you have a similar pattern, the best way you can help your child is to go make friends for yourself. Similarly, the bottom line with lying is that if it is a problem for your child, the very best way you can help your child is to do the courageous and difficult work of getting honest in your own life.

We need to be absolutely honest with our children and especially with ourselves. Blanton talks about three levels of honesty, in ascending order of both subtlety and difficulty: honesty with the outer facts or circumstances, honesty with how you feel about these circumstances, honesty with the deeper conditioning (distress) that lurks behind all this. I would say that a necessary first step is to completely surrender the illusion that there is any justification whatsoever for you to blame, punish, or otherwise be out of your loving with your children; it’s all your distress, your responsibility.

Step 5) Do the inner work related to the difficulties you have in the area of distress. This might mean personal counseling, talking with friends, journaling, whatever support helps and is necessary.

Step 6) Be grateful to your child for being your teacher and pointing out to you the place you need to grow.

Any place where we get restimulated and reactive becomes another portal into the fires of personal transformation, and our children are the catalysts who provide both the stimulus to feel the fire, and the motivation to stay with it and endure the ordeal of countless ego deaths. If we are fortunate, these are deaths of those negative memories, feelings and habits which keep us out of our loving, and awakenings into greater space for acceptance, tolerance, compassion and clear thinking about our children and ourselves. I wrote about one of many personal examples in a chapter of my Wildest Colts book; the chapter was titled “About Eric,” but in retrospect and consistent with the teachings herein, I am clear that the title should be “About John!” A short version of the story is that my son was angry much of the time between ages 4 and 7, or so it seemed to me. No doubt he had reason, but it is also true that young children do get angry a lot as they face inevitable insults and injuries to their big desires and great imaginations. And if they are given free reign to express themselves, they are often quite dramatic. In any event, Eric was young and powerful and expressive, and his mother and I joked that his ego was so much bigger than ours. I certainly felt and thought that his personality was very different than mine; fact is back in my mid-20’s I had been tagged by at least one good friend as “the ultimate rational man.” I was logical and stoic, and in fact pretty shut down around anger.

So faced with my son’s intense anger, I was faced with one of those big points where, as I said in the dedication to my book, I either suppress Eric, or distance myself and withdraw, or…. allow the intense demand of his spirited nature to force me, kicking and screaming to transform myself and my life in ways I could never have imagined, again and again and again. . . One great thing about being a parent is that having a child is about the strongest motivator on the planet toward overcoming resistance to look at ourselves and change. I was determined to do whatever it took to hang in and stay close with my son, and so I did the hard work of facing my anger, and hanging in there with his. I went to counseling, I did men’s groups, I did play groups, and I changed, and I stayed close with Eric. I brought back the gifts of being more powerfully in touch with my own righteous anger, and more relaxed and confident in the face of my son’s.

Eric’s mother and I accepted the call to resist the three potentially oppressive institutional forces cited above. Our boy was not interested in reading until after he turned eight. He loved to be read to, but when I tried to get him to read Hop on Pop, he threw it at the wall. Imagine how that would have gone over in school! We enjoyed an occasional video, a favorite being Lady and the Tramp, and he was into Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles for a while, but mostly he played, indoors and out. I imagine that many of you readers can imagine some of the judgments we got about ourselves, and our boy, during those tumultuous times of attachment parenting and free expression. More than a few folks were on occasion of the opinion that I ought to consider a psychiatric consultation for both Eric and myself. We were operating largely on faith and principle at the time, so I offer my own now emerging and young adult children as encouragement to those of you still in the fires of intensive parenting. Eric is living a big life in the epicenter of the art world with a great job in a premier Manhattan gallery. Vanessa, now 25, is in graduate school at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon. Our youngest is 22, back in Austin after graduation in May from Hampshire College. He is a writer, among other interests.

Three Parenting Keys

Part of this Consciously parenting includes a series of “wisdom nuggets,” which will be sent out regularly during the three weeks of my segment. I will conclude this initial essay with a small sampler of three ideas that have been of value to me. The first is in my view the big kahuna!

To see your child through the Eyes of Delight is the greatest gift in the world you can give to your child and to yourself.

This should be our lodestar by which we navigate the great sea of parenting. If we see through these eyes most of the time, all is well, and we can handle the rough spots. When we are seeing this instead through eyes of judgment, rejection, hopelessness and such, we can know we are off course and do whatever it takes to reclaim our eyes of delight. That would be the work. Here is a valuable corollary:

Remember NOT to trust the thinking of anyone who sees your child through anything other than the eyes of delight. There really are no “bad” children. Your child is completely good and delightful.

Here is a humbling and important teaching about respect. Adultism is the systematic mistreatment of children and young people simply because they are young. The overall conditioning against emotional expression is laid down through adultism. The pattern is one of massive disrespect. To test whether or not you are acting as an agent of this oppression, apply the following question to any action you take toward a young person: Would you treat another adult the same way? Since we are all thoroughly conditioned to treat children a certain way, we must make every effort to challenge our conditioning. Complete and unqualified respect is and must be the foundation stone of any mutually satisfying relationship, and must be the basis from which we enter into relationships with our children. Without it, we all inevitably end up in humiliation and disgrace. The way to teach respect is to give it. The only way your child will learn the true meaning and experience of respect is through being consistently treated with respect.

My third and final offering for the moment is a reminder about perspective. The environment that matters most is not the one we construct for our children; it is the one given them by nature. Nature contains us and, borrowing a Native American expression, each of us is born with a capacity to experience awe and wonder for “All my relations.” Our task is to reclaim or redevelop this natural capacity and to protect and nurture its reality for our children. From this place flows an enduring and abundant spring of clear, clean motivation as we live in our natural state of connectedness, of caring, of compassion, of love and reverence, knowing beyond any doubt that all life is sacred. Take some time now, and later, to play and explore outdoors with your children

Featured photo Shutterstock/AlpaSpirit