The Nurture Balance Sheet: How Much Is “Undercare” Costing Us? Part Two

This is a two part series. This is Part Two: Why Fathers Provide The Solution. Read Part One: Investing In The Evolved Developmental Niche here.

![]()

To varying degrees, a compromised first year of life is the norm, because factions of our society rail against any aspect of parenting seen as interfering with women’s career advancement. The ability to return to the workplace quickly and seamlessly is considered paramount. Child development advocates like Darcia Narvaez, PhD, argue that our values are due for a upgrade (see part one of this post). Should we sacrifice our careers somewhat for healthier children and a more compassionate society? Probably. But what if that sacrifice was only on the surface and short-lived?

What if in the long run, the investment we make in our children through Narvaez’s Evolved Developmental Niche (EDN) parenting strategies paid dividends at the individual, corporate, and societal levels? What if this investment in very early child development improved the productivity of nations, saved billions on healthcare costs, and even better equalized the gender gap in the workplace?

The Projected Savings of High-Nurturing

At the individual level, the benefits of extended breastfeeding and ample loving touch—the core of the EDN—are obviously palpable. We want to give these gifts to our babies. But the mental health savings of investing in the very early years (primarily the first year) can be as well, simply by considering the mental health crisis and among other things, the work of Allan N. Schore, PhD, who shows its roots in infancy.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, four million children and adolescents in the U.S. suffer from a serious mental disorder that causes significant functional impairments at home, at school, and with peers. Of children nine to 17 years old, 21 percent have a diagnosable mental or addictive disorder that causes at least minimal impairment. We’re given a convenient scapegoat for this, of course: darn genetics. But health crises don’t reach epidemic proportions because of genetics. Evolution happens through genes, but epidemics occur too quickly. There has to be something going on in the environment. In this case, in the emotional and social environment of the first year or so of life. (Read a presentation by Dr. Allan Schore about how early child rearing quality creates protection against versus risk for mental illness.)

The Next-Generation Savings of High-Nurturing

John Beddington, PhD, has extensively studied the “mental capital” of economies, which will prove vital to the future success of nations. Mental capital is defined as encompassing both cognitive and emotional resources, including, as he states: “flexibility and efficiency at learning; and emotional intelligence, social skills and resilience in the face of stress.” Beddington’s definition bears a striking resemblance to the outcomes of Narvaez’s EDN (discussed in Part One of this post): Higher social and emotional intelligence, better learning and memory capacities, stress resilience, and greater compassion and cooperation. In concert with Narvaez’s assertions, the genetic contribution to the “mental capital” Beddington researches, by his own account, is well below 50 percent in childhood, and it’s only that high because of intelligence. Tease IQ out and the emotional and social capacities are even less genetically determined—hovering around 20-30 percent, if they exist at all. Even when looking at genes, as the burgeoning field of epigenetics reveals, we’re rarely looking only at genes: “Genes are themselves inert,” Narvaez states in her latest textbook, Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality: “They do not act alone but require an interactive context of environmental influence, maturation, and action.” Add to that, even when a mentally detrimental gene gets activated by the environment, a change in that environment—such as, perhaps, receiving EDN-conducive parenting—can limit its influence on the child’s future mental well-being. Genes are not destiny.

This is why biologically-informed parenting practices confer the best chance for optimal development of mental capital within any given set of genetics. This is especially true during the first year of life when the foundations of mental health and social and emotional capacities are forming.

So, let’s look at the numbers to address the obvious question emerging: How much does mental illness cost us versus the investment in mental-health-promoting childhoods (i.e., the EDN)? The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) cites a cost of $150 billion for mental health care in the U.S., roughly equivalent to the cost of cancer care. (One third of this is eaten up by anxiety disorders.) And that’s just the cost of treatment.

Without treatment, the consequences of mental illness for the individual and society are enormous. Unlike cancer, the economic burden of mental illness is not only the cost of care, but unemployment, absenteeism, substance abuse, homelessness, inappropriate incarceration, and a myriad of indirect costs due to chronic disability that begins early in life. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the economic cost of untreated mental illness is more than 100 billion dollars each year in the United States. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that four of the 10 leading causes of disability in the US are mental disorders. Something beyond genetics is happening here, just by virtue of the rate at which it’s getting worse. Depression across the U.S. is now between 10 and 20 times the rate it was 50 years ago while its average age of onset is a decade younger.

We’re now up to $250 billion in costs. But due to another law of our biology—we can’t separate mind and body—the costs don’t stop with mental health. The contribution of early intense stress (i.e.: cry-it-out sleep training, touch deprivation, infant isolation) to later disease and degeneration has an astonishing effect on life-long productivity. This is too complex to assign a number, but one example of these effects provides a good starting point: The Journal of the American Medical Association recently reported that conditions in the U.S workplace such as arthritis, headaches, and back problems cost nearly $50 billion per year. These types of ailments are being increasingly linked to early, chronic childhood stress, as the work of Robin Karr-Morse exposes. But there are innumerable other diseases with stress correlations.

The Immediate Savings of High-Nurturing

We wouldn’t even need to wait a generation to begin realizing a hearty return on an EDN baby-rearing investment. More breastfeeding alone could save $26 billion per year in medical-care costs, based on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health (OWH) calculation of 90 percent of babies being breastfed exclusively for the first six months saving $13 billion; extended breastfeeding confers additional health savings. Caring for a sick child also enters the equation quickly in terms of current loss of productivity, because it takes the worker out of commission just as surely as the worker being ill herself does. Employee absences due to caring for sick children in the United States costs businesses approximately $3 billion dollars every year. While breastfeeding, especially the EDN’s exclusive and extended variety, reduces babies’ risks of virtually all infection and when a breastfed baby does become ill, he will typically recover far faster and with less medical intervention. Formula fed babies, on the other hand, are at increased risk for allergies, Type 1 and 2 diabetes, Crones disease, ulcerative colitis, dental cavities, certain types of cancers, including childhood lymphomas, and more.

Since breastfed babies are statistically healthier than their formula fed peers, the parents of breastfed babies spend less time out of work and less money on health care. This point illuminates the need for not just longer maternity leave to improve breastfeeding rates, but better breastfeeding and pumping accommodations at work so moms don’t have to sacrifice breastfeeding to maintain their careers. Much of the opposing debate has centered on what breastfeeding costs in terms of short term career productivity, but even the study much cited to assert this breastfeeding blamesuggests the solution isn’t less breastfeeding, but rather more workplace accommodations. The study authors note:

“Should breastfeeding be shown to have a negative impact on work outcomes, our study will provide evidence that breastfeeding promotion needs to be coupled with protections for women’s work and earnings“.

Such protections would really benefit the company, too, even beyond lower health care costs. This is because even if we manage to get enough quality baby care to go back to work at 12 weeks post partum, how much are we really able to give to our jobs in that dizzying first year? The corporate problem of workers reporting in while not well (for a variety of reasons) has become so financially detrimental that the term “presenteeism” was coined to describe it. Presenteeism is defined as the practice of employees not operating to their usual level of productivity due to illness or extreme fatigue.

Could there be a better exemplar for this than the first year of parenthood? We’re only human, not machines, and as biology dictates—neither are our babies. They demand what they need and our jobs gets what’s left of our energy—or vice-versa, and then we’re back to an increased mental health risk. The total cost of presenteeism to U.S. employers has been increasing; estimates for current company losses range from about $150 to $250 billion annually. Depression alone set U.S. employers back some $35 billion a year in reduced performance at work, not counting when depression takes them out of work (absenteeism).

So how much savings from the presenteeism problem could an EDN-based society enjoy? The National Women’s Law Center estimates that women giving birth represent 1.6 percent of the workforce. We’ll double that figure to count the father in the equation (3.2 percent of 200) since, if he’s pulling his weight in the post-partum months, he’s suffering from presenteeism too. This equals a cost of just over six billion dollars attributable to baby-induced presenteeism alone.

Adding both the immediate and future savings outlined above, let’s calculate how much of that $332 billion could be saved with child rearing closer to what nature intended. This is a conservative approach, not fully weighing in the percentage of immeasurable costs attributable to chronic physical illness (other than mental) at an additional $500 billion. If at least 70 percent of child mental health is determined by early parenting practices (on average, 30 percent is “genetic” [note limitations of this stat above]), and the EDN is correlated with better mental health outcomes, then let’s say the EDN-experience for all babies could cut future mental disorders by 70 percent. Let’s use the same percentage for just those several ailments know to be tied to mental health (although we know most others are, too), plus the whole $26 billion in savings for breastfeeding and six billion from presenteeism, for a total of around $242 billion.

Alternatively, some combination of longer leave, flexible work hours, and higher quality childcare conducive to the“multiple caregivers who are all bonded to baby” element of the EDN could help realize similar savings. Now, how does this compare to the short-term cost of a more reasonable six-to-12 month paternal leave (divided between two parents)? Leave it to breastfeeding advocate, KellyMom, to calculate a figure of $113 billion for one year of leave paid at 75 percent of the mom’s normal wages, for all mothers. (Since men earn slightly more, the cost to share leave with dads would be around ten percent higher, though better for the economy as detailed below.)

So considering the costs, investing in support that allows for the EDN would pay for itself more than twice. It’s no coincidence that the developed countries with the best paternal leave policies tend to have the lowest incidence of mental disorders (e.g.: 26.4 percent of people in the United States compared to 8.2 percent of people in Italy.) Of course more reasonable paternal leave doesn’t guarantee adaptation to the EDN persuasion of child rearing–a limitation of my numbers. A parent taking a 12 month leave may still execute cry-it-out sleep training, for example*. This means parent and clinician education is also in need of some attention and funding to have additional impact on child mental health. But longer paternal leave makes the EDN possible, and with an over $100 billion in net savings, there’s more than enough to enhance it in additional ways.

*Please note, I’m not referring to allowing an older baby to self soothe for a few minutes of mild fussing, but rather an intense cry that is ignored and therefore triggers the baby’s stress response system. (For a detailed explanation of the distinction, please see my post on Dr. Narvaez’s blog.)

High-Nurturing and the <strong “mso-bidi-font-weight:=”” normal”=””>Gross National Product

So why is our society, so afraid to invest in high-nurturing very early childcare? Because we fear it poses a threat to our productivity—to success. Those of us pleading for more support for families with young children can typically be found lobbying for a compromise: more attention to better parenting and less to the bottom line—a matter of values. When we define success more completely than only temporary productivity, the cost-benefit equation shifts. When we realize that success is most probable in a society made up of more healthy, functional individuals, our parameters broaden—perhaps even wide enough to support, not just breastfeeding, but the entire the EDN protocol. But recalibrating values is not the entire case to be made.

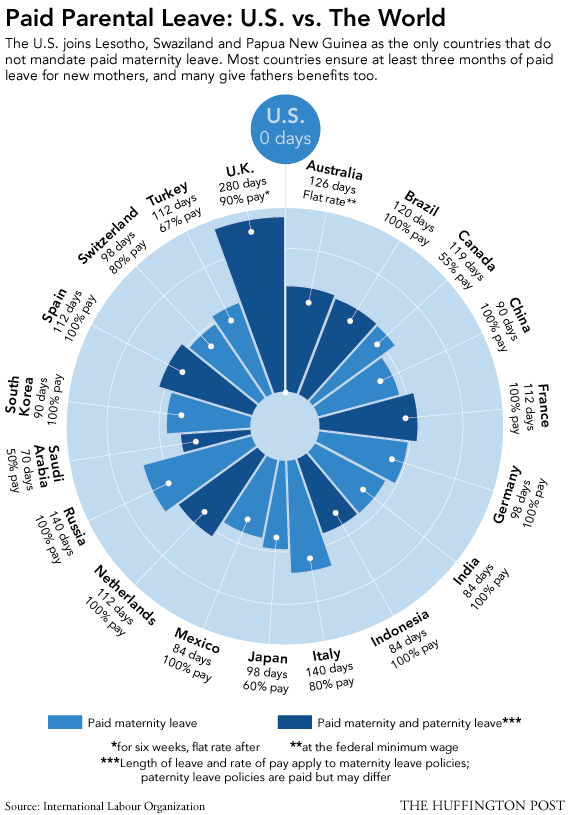

Research shows that in the long-term, the same solution of several (longer maternity leave) to what Narvaez describes as undercare in our society would get more women in the workforce and increase national productivity, too. All over the globe, paid maternity leave policies have proven vital in boosting the likelihood that a new mother will return to work, and will put in more hours after she returns.

The Women’s Movement Re-engineered

Still, to factions of the women’s movement, the idea of intensive childcare biting an entire year’s progress off of women’s careers is a tenuous if not treasonous one. But here’s what they miss: longer maternity leave preserves a woman’s career in the long-run. Instead of giving up on careers altogether, because a non-paid six or 12 week leave is cruel and unreasonable, more women are likely to recover properly, adequately nurture their offspring—and then go back to their jobs. Japan recently put its money on it: Prime Minister Shinzo Abe increased Japan’s maternity leave policywith the goal of boosting the country’s GDP by 15 percent. Goldman Sachs revealed, in a paper in April of this year entitled “Women’s Work: Driving the Economy,” that higher numbers of educated and skilled women in the labor force can boost competitiveness and generate growth with little incremental cost. Credit Suisse cites research suggested one reason more women with careers equals a healthier economy: Greater gender diversity in leadership improves communication and reduces corrosive competition among senior managers. Goldman’s earlier research showed that closing the gender gap in developed countries could push income per capita as much as 14 percent higher than their baseline projections by 2020, and as much as 20% higher by 2030. And longer—not shorter, or nonexistent—maternity leave is what will get us there.

In return, all we ask is for is one year to give the next generation the nurturing it needs to thrive. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing and psychological evidence suggests that women want both: work and mothering.

And so, by the way, do men. Equalizing the gender gap may lie squarely on fathers taking more time off with their babies. When men participate more in childcare in the first year, women’s careers benefit and so does the economy. It’s a simple investment: put in one year of leave, and get out 20 or 30 years of additional productivity. Economists predict that if American women worked at the same rates men did, U.S. GDP would be nine percent higher. More men fathering in the first year and more women working thereafter could turn the inequitable childcare tradition on its head—without denying the natural needs of babes. Extended parental leave for both parents, could keep even more women in the workforce, raise economic productivity, and give the women’s movement the genuine equality it seeks—in one fell swoop. Not to mention, it would allow dads to enjoy the deep fulfillment of a more hands on approach to raising their own children.

Read Part One: Investing In The Evolved Developmental Niche here.

Featured Photo: Shutterstock/Max Topchii

![Paid Family Leave Graphic]() Paid Parental Leave Resources

Paid Parental Leave Resources

Kindred’s Articles and Videos on Paid Parental Leave

Center for Parental Leave Leadership

PL+US, Paid Family Leave for everyone in the US.

MoveOn.org Paid Family Leave Petition

National Partnership for Women and Families

The Family And Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) Act

Paid Family Leave/Paid Family and Medical Leave Research

Other Federal Paid Leave Legislation

More on Maternity Leave from MomsRising:

![Motherhood manifesto]() Know the Facts

Know the Facts