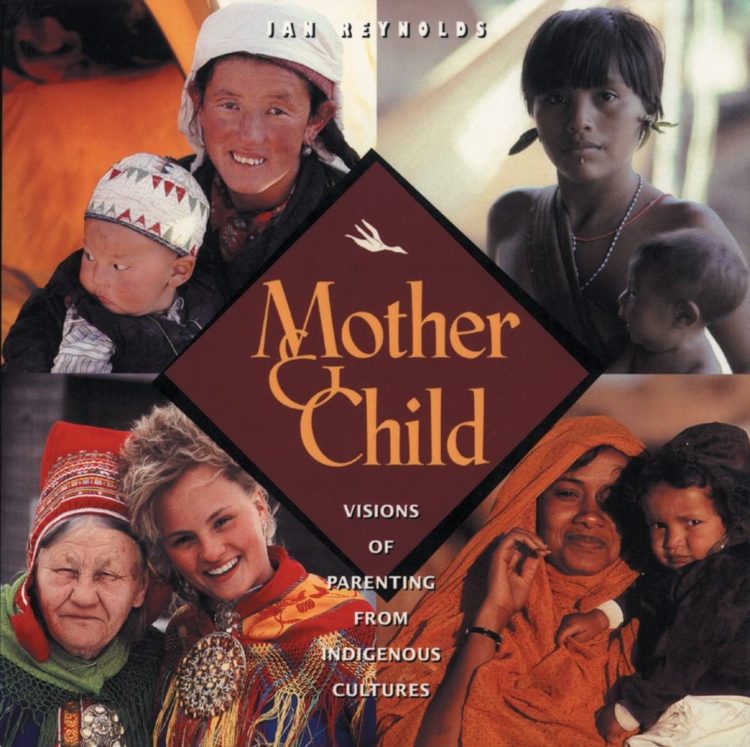

Award-winning journalist and photographer, Jan Reynolds, has lived and traveled with indigenous mothers around the world. From above the Arctic Circle to the Himalaya, the Sahara, Finmark, the Aboriginal outback, the Amazon territory, and Mongolia – Reynolds has seen and shared directly these women’s age-old ways of loving and teaching their children. Reynolds’ writing is complemented by her photography as she gives both equal weight in conveying what she learned from these mothers, “… that the natural world has eternity in it, and a mother’s instincts during pregnancy, birth, and child rearing links her to this eternal chain of life.”

Reynolds’ respect for both the indigenous peoples and the land itself is evident as she shares her discovery of how a deep connection with the natural world strengthens the primal nature of the mother-child bond, giving these women the confidence to connect with their own offspring and to trust in their natural instincts while handling them.

Reynolds’ respect for both the indigenous peoples and the land itself is evident as she shares her discovery of how a deep connection with the natural world strengthens the primal nature of the mother-child bond, giving these women the confidence to connect with their own offspring and to trust in their natural instincts while handling them.

The baby was given every human signal that would nurture a sense of security….

Newborns were nursed, held, or carried by their mothers from the moment of birth. As toddlers, they joined their mother as she went about her daily chores. Following and mimicking mother, the children were “a thread in the weave of their daily life.” Whether it be foraging for food, or tending a fire, a child assumed only as much of the task as he or she showed interest in. At night, most of the families slept together.

Reynolds found that the children were remarkably poised and self confident, and remained so as they grew into adolescence. She saw this to be the outcome of their having received so full a measure of security and every affirmation of belonging in the early years. Learning the ways and values of their culture through direct, tangible examples and participation, they grew naturally into independence. Shared activities enabled them to grow into confident, caring, young adults. One result of this self-confidence was the strong bond of friendship apparent between peers.

Self assured children are less likely to be aggressive, need less supervision, and are more interested in playing together.

She noticed that while parents in the west tend to dive in with solutions whenever possible, for the most part the indigenous children were left to solve their own curiosities and settle their own grievances–in this way they learned that they could achieve on their own.

Through these pages I came to appreciate–with awe and wonder–the lives of these people and their home lands. I learned of the Tuareg, a matrilineal society deep in the heart of the Sahara. Here the men, not women, wear veils. When the time comes for marriage, the women choose the men. And it is the woman who passes on the family wealth and name. I read with fascination of the lives of the Yanomama–the largest primitive tribe still living on earth–in the Amazon. They have no words for time of day, other than high noon; and still hunt with a bow and arrow. I loved learning of how a child is born and cared for by the Inuit of the Arctic, an area known for being consistently the coldest spot on earth. And of how the Inuit clean house–they build a new igloo and leave the other behind.

For those people, who live in complete harmony with nature… this custom works. When everything utilized by the culture comes from the land, it can simply return to the land and no harm is done.

Reynolds writes too, of the time when a mother becomes a grandmother and enters her “twilight years.” Seldom trapped by ego and vanity, she becomes the source of cultural stability, “…the link between what was and what is now…. If mother is the heart of the continuum, grandmother is the soul.”

In this book, you will meet these women, their families, and the earth they live on–each embodying a wisdom worthy of our attention, today. Noting that is was not until she had a child of her own that she recognized the applicability of their ways to her own life, Reynolds offers suggestions for ways that mothers in the western world can incorporate this indigenous wisdom into their own lives. She offers examples of how keeping the ways of the indigenous in mind helped her to see workable and caring options that were not initially obvious or readily available. For example, when pregnant Reynolds remembered her indigenous friends who had hauled water in the Himalaya, and traveled on camel caravan in the Sahara, after consulting with physicians who concluded elevation was not a problem if she didn’t push herself aerobically, she headed off to Morocco to climb and ski Mount Toubkal for work projects of own.

When the time came to give birth, Reynolds–while appreciating the availability of backup medical facilities in case of complications–delivered at home with a midwife, as had the indigenous women she had seen. Having observed birth with the indigenous to be more of a change in environment than a separation between people, she saw to it that the newborn was immediately laid on her breast, where he was able to rest, nurse, and hear his mother’s voice and heart beat. Reynolds developed mastitis but again, having observed breastfeeding around the world she persisted in nursing, convinced as she was of the benefits to mother and infant. Having seen women around the world sleep with their infants, and carry their babies close to bodies at all times, she too readily adopted these practices.

Because I had seen how happy and effective the older indigenous children were within their community, I came to trust and appreciate the simple, instinctual ways of their mothers.

To women without the flexibility Reynolds has with her work schedule, she suggests other possibilities, among them coordinating with other moms to swap childcare for free time; arranging to take baby into work; working part-time from home; working less and doing with less money. The influence of the indigenous caused her to recognize many baby specialty items were not at all necessary.

And from these people, Reynolds learned about letting go. I resonated with her feelings of happiness at seeing her child move towards secure independence, feelings which run side-by-side with “that wistful feeling of wanting to be needed more.”

My indigenous friends taught me that their job as mothers was to teach their children, from the moment of birth, to live without them.

This little book is a treasure. A delight to look at, a pleasure to read–and to share with your children. Mother & Child can be read in an hour or two. A light introduction to continuum principles. Much of the material is conveyed through the photography.