How Not To Judge Families Sitting Beside You

How do we help ordinary families to understand what science is discovering about children’s development? How do we help tired parents feel more curious about their baby’s emotional needs? How do we help them to connect the dots, so that they realise their responses hold long-term, biological consequences for their children? If this little boy’s brain becomes addicted to the dopamine hit his father’s phone is supplying, the parents will soon have major ‘behavioural issues’ on their hands. And their little boy will suffer.

***

I spend most of my time these days thinking about how we get information to parents about infant brain development. ‘Brain development’ isn’t the right terminology, though. The English language doesn’t have a word for what I mean. I mean something more like the intersection of brain and body, self-awareness and self-regulation, anxiety and comfort, and the way that relationships underlie the development of all these systems. That’s the most crucial point for parents to understand: relationships matter.

Our Western society does not begin to comprehend the importance of relationships for children’s development. Our modern way of life damages our children – and ourselves – in ways we don’t realise. It happens without our intending or being aware of it. It happens because we are increasingly cut off from one another and from ourselves, even from our own bodies. We end up surviving, rather than thriving.

Let me tell a story to illustrate what I mean.

I was sitting in a café last week, watching a family who had come in to have a meal. Mum pushed the baby in his buggy, about 18 months-old, over to a table. Dad, Mum, and Big Sister put down their bags and coats. The three of them went over to the counter to choose drinks and food, leaving the baby parked beside the table.

I was sitting in a café last week, watching a family who had come in to have a meal. Mum pushed the baby in his buggy, about 18 months-old, over to a table. Dad, Mum, and Big Sister put down their bags and coats. The three of them went over to the counter to choose drinks and food, leaving the baby parked beside the table.

The baby immediately got agitated, wriggling and holding out his hands toward them, scrunching his face, and protesting very quietly. They didn’t notice, though, because their backs were to him, while they read the menu at the counter. Plus, they will have believed him to be safe, strapped into his stroller and parked near their things at the table.

As minutes passed, the baby’s arm movements and face got more frantic. His cries did not get louder, though; they stayed consistent and pleading, in their rhythm and tone. I found myself getting agitated. His family couldn’t see or hear him. He needed help to get their attention.

So I tried a technique that sometimes helps solve things when a baby is in need and parents are distracted. I like it because the parents don’t feel offended or blamed. I simply said to the baby, in an empathic voice loud enough for his parents to hear, “Oh, are you feeling lonely? Are you missing your Mummy over there? She’ll be back in a minute.”

My brief interjection helped Mum to turn around and realise her baby was needing her. She smiled at me as she came back to the table, and I smiled back at her. As she neared their table, the baby’s arms quit waving so frantically, and he relaxed a tiny bit, although his arms remained up in the air, as if he was hoping to be picked up.

That made sense to me. He’d been missing her, far across the room in this unfamiliar place, so stress hormones like cortisol would have been rising. His brain and body would instinctively have been craving a cuddle, since the reassurance would have brought the cortisol levels down. Oxytocin would have been boosted too, by her touch, and that would have relaxed him even more.

However, a cuddle is not what happened. Instead, Mum reached for the handle of the stroller, and moved it back and forth, trying to comfort him by the swaying of the buggy. I knew that wouldn’t work fully for him, because the swaying of your buggy isn’t the same as the warmth of your mum’s hug. But I didn’t know how to help the baby this time. No parent wants an interfering busybody of a stranger telling them how to care for their own child.

But the baby was still distressed. His low-level cries of protest continued; his face scrunched; his head hung down in a kind of defeat. Mum continued to ‘rock’ the stroller with one hand, leaving her other hand free to adjust the coats. She was now focused on making space at the table, and so she wasn’t looking at his face any longer. He had neither her gaze nor her touch to draw on for comfort.

Watching all this, I found myself thinking that her physical closeness would be helping him feel somewhat safer. The cortisol in his system should at least be levelling off, rather than rising higher. His overall state wouldn’t change rapidly, though. Cortisol stays in your system for at least 20 minutes – which is why reassuring touch in this situation is so helpful. Cuddles kick-start the decrease.

Very soon, Dad and Big Sister came over to the table, having made their choices. I wondered if the baby might now get a cuddle, or even a hand-hold, since there were more hands available. This seemed hopeful, because his distress hadn’t ceased. He was still quietly moaning and looking at the ground.

Let me pause in the midst of my storytelling. Before I go on, I want to consider what might be happening for you, Dear Reader. If I am telling this story vividly enough and compassionately enough, then maybe you will be feeling something of the anxiety I was feeling for that baby.

If he can’t get the comforting attention he needs from his family, then he has a problem. At only 18 months old, his brain is still too immature to fully comfort himself when he is distressed, so he has to look to an outside source for that comfort. Right there, in that café, in that very ordinary moment, he is learning lessons about where comfort comes from. It isn’t from his family.

Perhaps, in order to cope with your anxiety for the baby, you might be feeling frustrated with the parents. Why aren’t they giving him the attention he needs? That reaction of frustration or exasperation or even anger makes sense to me, because these emotions signal that a situation we are witnessing requires some sort of action. The trouble is that these emotions easily lead to judgement, and judgement is everywhere these days when it comes to parenting. Modern parents live with the constant anxiety of being judged harshly.

Consider, for instance, what recently happened to political correspondent Robert Kelly, when was he “interrupted” by his two young children while giving a live television interview to the BBC from his office at home (see the hilarious video below). His spontaneous response, along with that of his panicked wife (or perhaps nanny – the internet can’t decide), solicited all sorts of criticism from observers. Commentators on social media began arguing with each other over what response would have been most appropriate, and even the couple’s use of a baby walker was criticised. My own response was to wonder how I would have reacted as a parent, handling such an unexpected, personally exposing situation, being broadcast live on international television.

So, returning to my story, what happens if we counter any rising sense of judgement with curiosity? What happens if we wonder what was going on in that moment that kept this little boy’s parents from noticing his distress? Were public places uncomfortable for them? Had they had to walk a long way in the cold?

What happens if we expand our curiosity even further and wonder what might have happened for them within the last hour or earlier in the day or within their general family interactions? Had they just had an argument or come from a difficult doctor’s appointment? Was Mum suffering postnatal depression? Were they on the edge of divorce? Did they believe that electronic devices help young children to learn?

And what happens if I search for the words that help this story to prompt curiosity in readers, rather than judgement or anger or blame? Here are a set of ordinary parents, busy and tired and distracted by the tasks of modern life. They probably have no idea how scared babies can get, parked far away across the café in a stroller, or that cuddles have a biological impact on a child’s brain.

And what happens if I search for the words that help this story to prompt curiosity in readers, rather than judgement or anger or blame? Here are a set of ordinary parents, busy and tired and distracted by the tasks of modern life. They probably have no idea how scared babies can get, parked far away across the café in a stroller, or that cuddles have a biological impact on a child’s brain.

In that case, how would it be helpful to them if I were to get frustrated about something they did unintentionally? My curiosity will be more helpful than my frustration could ever be.

And, as it turns out, curiosity is going to be incredibly important for all of us, if we are to reach the end of this story in a compassionate place. Because it’s about to get worse.

The whole family is now at the table, with Dad sitting next to the baby. Mum and Big Sister are across the table, stretching out, having taken off the last of their coats. The baby, though, is still strapped into his stroller, unable to stretch out or shift his posture. His low level protest cries haven’t stopped, either. His head is still hanging down, moving slowly back and forth in a restless fashion.

Dad must have noticed though, because he moves to offer the baby a kind of comfort. He reaches into a bag and brings out a phone. He hits a couple of buttons, and hands it to the baby. It must be playing a video.

Sure enough, the baby’s whimpering stops, his head comes up, and his hands cease moving as they grasp the phone. His agitation fades almost immediately. He is intensely focused on the display on that phone.

I imagine that the father thinks he has comforted his child. Outwardly, he does appear calmer and happier.

As I watch the child’s fierce concentration, though, I think of the dopamine being sparked in his brain. Dopamine is the hormone of novelty. We human beings crave it. It’s the feel good factor. Dopamine is what gets triggered when we fall in love. Our brains and bodies yearn for it. We get addicted to it.

I knew I was watching a father comfort his son’s distress by fostering a biological addiction to technology.

And I knew the father didn’t know that.

And I knew that when the father would eventually try to take the phone away, the spike in the baby’s disappointment and distress was likely to cause a terrible, wailing conflict – which would further distress everyone in the family.

And I had no way to explain any of this to them.

Dear Reader, how am I doing? In telling this story, I am trying my best to turn you into a watcher, rather than a reader. I am trying to have you sit with me in the midst of that café, trying to decide what you would do, how you would feel, what you would think. I am aiming for that because, of course, we sit down next to ordinary families every day, whenever we walk into cafés.

How do we help ordinary families to understand what science is discovering about children’s development? How do we help tired parents feel more curious about their baby’s emotional needs? How do we help them to connect the dots, so that they realise their responses hold long-term, biological consequences for their children? If this little boy’s brain becomes addicted to the dopamine hit his father’s phone is supplying, the parents will soon have major ‘behavioural issues’ on their hands. And their little boy will suffer.

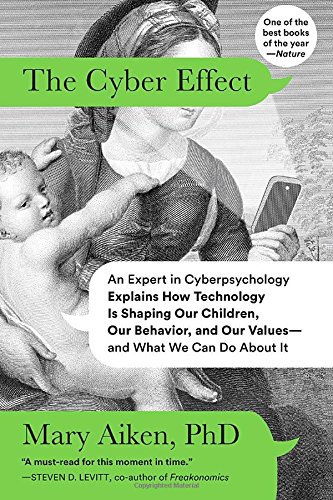

The points I am making are not novel ones. They are part of the reasoning underpinning recommendations by the American Academy of Paediatrics that children under two years of age should never view screens alone. Other organisations have used language shifts to emphasise the biological impacts, arguing that early technology use should be regarded not as an ‘educational’ or ‘cultural’ issue, but as a ‘medical’ one. The author Mary Aiken dedicates several chapters in her new book, The Cyber Effect, to exploring what is happening across our society as children encounter a mismatch between their basic physiological needs and their parents’ technology habits.

The points I am making are not novel ones. They are part of the reasoning underpinning recommendations by the American Academy of Paediatrics that children under two years of age should never view screens alone. Other organisations have used language shifts to emphasise the biological impacts, arguing that early technology use should be regarded not as an ‘educational’ or ‘cultural’ issue, but as a ‘medical’ one. The author Mary Aiken dedicates several chapters in her new book, The Cyber Effect, to exploring what is happening across our society as children encounter a mismatch between their basic physiological needs and their parents’ technology habits.

I found myself thinking about all this guidance as I watched the final stage of this family’s interactions. The story doesn’t end happily.

With the baby now (apparently) settled and engaged with the phone, Dad again reached into a bag. I realised he was taking out his son’s lunch, probably because there was a gap of time available before his own order arrived. He could feed his son before eating himself.

And that’s what Dad proceeded to do. He fed his son, spoonful after spoonful of packaged food going into his mouth — while his little boy never took his hands off the phone or his eyes off the display.

The baby didn’t protest. He didn’t shake his head or refuse. He passively accepted each spoonful of food the father delivered to his mouth. His father looked relieved it was going so smoothly.

I knew, though, that this experience meant the baby was not engaged at all with his own body. He wasn’t developing a conscious awareness of hunger or how to take care of feelings of hunger. He wasn’t consciously learning about feeling ‘full’ or about ‘relief’ or about ‘companions’. What he was learning was that you solve uncomfortable feelings with technology.

The more the baby’s brain experiences that solution, the more the child will be out of touch with his own body. His internal teddy bear (to use the language I frequently use) will be weaker, less able to comfort him from internal, self-regulatory sources. He will become more dependent on external sources of comfort, turning to solutions like videos or games or drugs or alcohol or food. It sounds extreme, to knit these outcomes together, but it is exactly what the research on addiction is teaching us.

I knew I was watching a father nurture an addictive personality within his infant son. I also knew he had no idea that’s what he was doing.

As I stood to leave the café, 15 minutes later, the rest of the family’s meal was being delivered by the waitress. Dad could relax. His son was fed and was engaged in an activity. He could have his own lunch in peace.

I have no idea what havoc may have descended when it was time for Dad to take the phone away.

That family has clearly stayed with me. A week on, I’m still thinking about them – and now I’m writing about them, telling their story to a wider world, in the most compassionate way I know.

My hope is that their story, unknown even to themselves, might help other parents feel more curious about what’s going on in their children’s brains and bodies. And I hope it might help those of us trying to support families, to feel more curious about the unknown struggles going on in parents’ lives.

Curiosity is always more powerful than judgement.

Featured Illustration Shutterstock/Katerina Davidenko

Watch Suzanne Zeedyk’s documentary film trailer for The Connected Baby below, and visit the website here.