Natives Foster Happy People Without Overthinking

In 1975, Jean Liedloff shocked Americans with her book, The Continuum Concept: In Search of Happiness Lost. She reflected on her multiple stays in the Amazon living with the Tauripan, Yequana, and Sanema peoples, who were healthy and happy beyond her imaginings.

She was amazed at the differences in child-raising between the US and these “primitive” people. They were far from primitive but intuitively loving towards their children, raising intelligent and healthy adults.

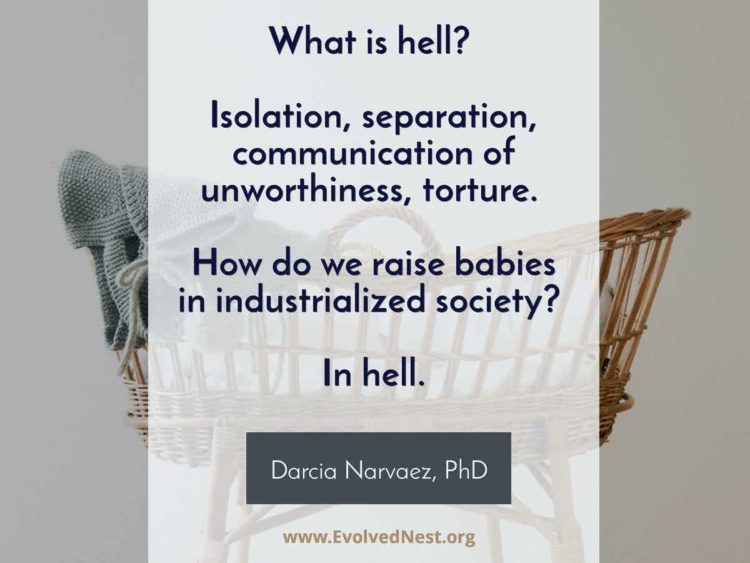

She suggested that U.S. child-raising practices were undernourishing or even destructive, with the results that U.S. babies were very unpleasant, unwelcome in workplaces and parties:

“They usually shriek and kick, wave their arms and stiffen their bodies, so that one needs two hands, and a lot of attention, to keep them under control.” (p. x)

Liedloff noted that it was easy to tell the difference between babies who were physically “in arms” for much of a 24-hour day and those who were not. The former had flexible body tone and the latter “felt like pokers” (p. x).

She advocated taking (well-nurtured) babies to work instead of isolating mothers and children in their homes:

“We need to recognize that, by treating babies the way we did for hundreds of thousands of years, we can be assured of calm, soft, undemanding little creatures. Only then can working mothers, unwilling to be bored and isolated all day with no adult companionship, rid themselves of their cruel conflict. Babies taken to work are where they need to be—with their mothers; and the mothers are where they need to be—with their peers, not doing baby care but something worthy of intelligent adults.” (pp. x-xi)

Babies expect to be embedded in an active living community, not the center of attention but an observer.

“A baby’s expectation is to be in the midst of an active person’s life, in constant physical contact, witnessing the kinds of experience he will have later in life. His role while in arms is passive, with all his sense observant. He enjoys occasional direct attention, kisses, tickles, being thrown in the air, and so on. But his main business is to absorb the actions, interactions and surroundings of his caretaker, adult or child. This information prepares him to take his place among his people by helping him to understand what they do. To thwart this powerful urge—by looking inquiringly, so to speak, at a baby who is looking inquiringly at you—creates profound frustration; it manacles his mind. The baby’s expectation of a strong, busy, central figure, to whom he can be peripheral, is undermined by an emotionally needy, servile person who is seeking his acceptance or approval. The baby will increasingly signal, but it will not be for more attention. It is actually a demand for the appropriate kind of experience. Much of his frustration is due to his inability to make his signals (that things are wrong) bring about anything right.” (p. xiv)

Over her multiple visits to the Amazon, Liedloff reflected on what felt right or wrong — for a baby and for herself. For a baby carried virtually 24/7:

“The feeling appropriate to an infant in arms is his feeling of rightness, or essential goodness. The only positive identity he can know, being the animal he is, is based on the premise that he is right, good, and welcome. Without that conviction, a human being of any age is crippled by a lack of confidence, a full sense of self, of spontaneity, of grace. All babies are good, but can know it themselves only by reflection, by the way they are treated … Without the sense of being right, one has no sense of how much one ought to claim of comfort, security, help, companionship, love, friendship, things, pleasure or joy. A person without this sense often feels there is an empty space where he ought to be.” (p. 34)

Liedloff felt that she and her fellow Americans were crippled in this way, having never developed a sense of innate goodness. Instead of finding rightness in herself, she needed outside reassurance that she was worthy, but this could only be superficial.

“Ever more frequently our innate sense of what is best for us is short-circuited by suspicion while the intellect, which has never known much about our real needs, decides what to do. It is not, for example, the province of the reasoning faculty to decide how a baby ought to be treated. We have had exquisitely precise instincts, expert in every detail for child care, since long before we became anything resembling Homo sapiens. But we have conspired to baffle this long-standing knowledge so utterly that we now employ researchers full time to puzzle out how we should behave toward children, one another and ourselves. It is no secret that the experts have not “discovered” how to live satisfactorily, but the more they fail, the more they attempt to bring the problems under the sole influence of reason and disallow what reason cannot understand or control.” (pp. 21-22)

We’ve moved so far away from following instinct and shaping intuition about what is good for a baby, for the self, that we create problems we think can be resolved by experimental research. She argues that if we provide babies with what they need, as part of the human species, they will develop health and happiness. She describes how the newborn expects the species’ developmental niche or evolved nest to fulfill basic needs.

“Fresh from the series of expectations and their fulfillment in the womb, the newborn infant is expectant, or, more accurately, certain, that his next requirements will also be met … his place in arms is the expected place, know to his inmost sense as his place, and what he experiences while he is in arms is acceptable to his continuum, fulfills his current needs and contributes correctly to his development.

Again, the quality of his awareness is very different from what it will become. He cannot qualify his impression of how things are. Either they are right or not right. Requirements are strict at this early date. As we have seen, he cannot hope, if he is uncomfortable now, that he will be comfortable later. He cannot feel that “mother will be right back” when she leaves him; the world has suddenly gone wrong. Conditions are intolerable. … nothing in his evolving ancestors’ experience has prepared him to be left alone, asleep or awake, and even less to be left alone to cry.” (pp. 33-34)

The book is still shocking to read because of the contrast to most U.S. babies’ experiences. Recently, neurobiological sciences are providing empirical evidence for some of Liedloff’s insights and the importance of evolved, nested early experience (e.g., Narvaez, Braungart-Rieker, Miller-Graff, Gettler & Hastings, 2016; Narvaez, Pankepp, Schore & Gleason, 2013; Narvaez, Valentino, Fuentes, McKenna & Gray, 2014). In the podcast below, Mary Tarsha and I give it a thumbs up in terms of meeting Evolved Nestcomponents.

References

Liedloff, J. (1977). The continuum concept: In search of happiness lost. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

Narvaez, D., Braungart-Rieker, J., Miller, L. Gettler, L., & Hastings, P. (Eds.) (2016). Contexts for Young Child Flourishing: Evolution, Family and Society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Narvaez, D., Panksepp, J., Schore, A., & Gleason, T. (Eds.) (2013). Evolution, Early Experience and Human Development: From Research to Practice and Policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Narvaez, D., Valentino, K., Fuentes, A., McKenna, J., & Gray, P. (Eds.) (2014). Ancestral landscapes in human evolution: Culture, childrearing and social wellbeing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.