KEY POINTS

- The list of disconnecting childhood experiences is long.

- Adults spend much of their lifetime trying to repair the disconnection that started in childhood.

If one understands our millions-year-old history as a species, the lifeways of mammals and other nurturing species, it’s easy to notice many violations these days of the standards that developed over the course of evolution for raising offspring. Evolution prepared us for nearly constant immersion in enjoyable social relations at every age. Technical-industrial culture is focused on wage work, money-making, and immersion in technologies. We did not evolve for this.

One of the most damaging, although perhaps most common, experiences for children today is disconnection. Young children need more connection than the rest of us—the physical presence and comforting of stable caregivers.

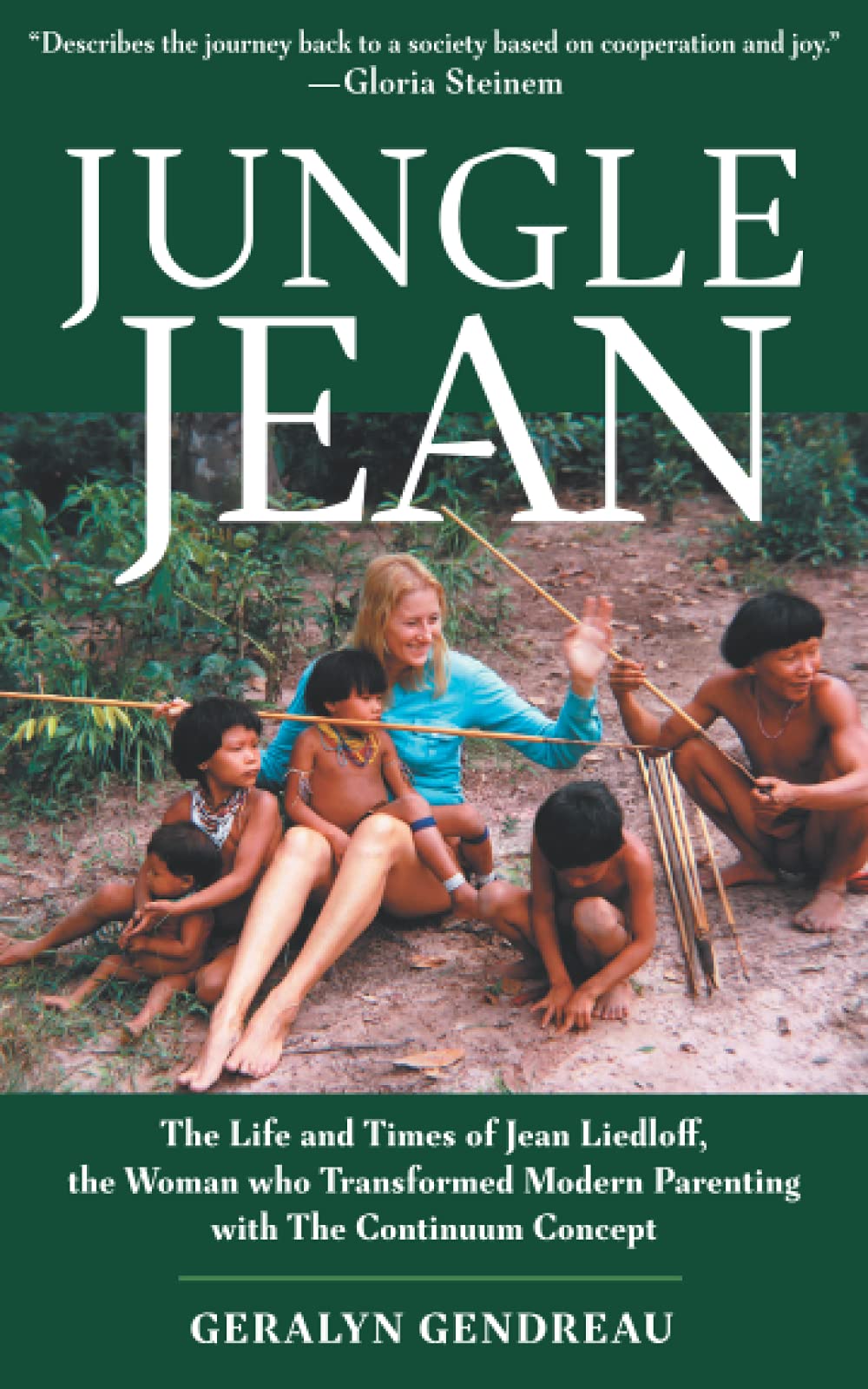

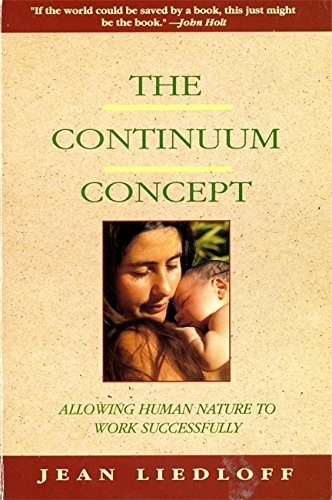

Disconnection was most famously noted and described as the breaking of the “continuum” by Jean Liedloff in her 1975 bestseller The Continuum Concept. A new book, Jungle Jean, discusses her life.

Liedloff shocked and inspired American parents by contrasting the lifeways and child raising of the Western world and peoples of the Amazon, whom she visited repeatedly for months at a time. The Amazon Yequana were happy and healthy (though aided by her first-aid kit), content to be alive, whereas she found her fellow New Yorkers (in the 1950s and 60s) tense, simmering constantly with hostility, fear, or dread. She lay the causal foundation at the foot of childraising differences.

In the Amazon, children’s needs were met without question, rather than controlled (e.g., sleep training) or minimized (e.g., “babies need to be taught independence”). Amazonian children were carried and kept “in arms” most of the time until mobile. The communities followed the principles of the evolved nest, which together support optimal psychosocial and neurobiological development (Narvaez, Panksepp et al., 2013).

What does disconnection look like for young children? Here are some of what Liedloff observed in ordinary American families.

- Physical separation that the child does not choose

- Babies out of arms (off of caregiver bodies) for hours at a time, left in devices (e.g., cribs, strollers) for extended periods of time

- Separation from family activities

- Left in distress

- Spanked or painfully punished

- Scolded

- Emotionally shut out

- Communications ignored

- Efforts at connection misrecognized and punished

- Efforts at learning from actions misrecognized and punished

- Movement in the world tightly controlled

- Lack of confidence in the child’s capacities

- Child “badness” expected

- Caregiver detachment—emotionally absent

- Prevention of natural movement outdoors

After childhoods of disconnection, adults spend a great deal of time, money, and anguish in either numbing their loneliness or trying to get back to a feeling of connection –to self, others, the universe.

Even if childhood was one of connection, we can find ourselves feeling disconnected in adulthood. Living in an urban area where we encounter many strangers each day and/or spend time in non-nurturing environments does not help. Sometimes our efforts at reconnection can go awry, for example, if we join a cult or exclusive group because it seemed to offer the desirable connection but instead leads to doing things we would not otherwise choose to do.

One of the benefits of the pandemic forcing people to stay home is parental presence with young children. Although every age needs to feel connected, cherished, and like they belong, the young child is particularly affected because it is the time in life when a person is self-organizing brain functions and expressions around day-to-day feelings and experiences.

Once we realize how important connection is, we can make efforts to establish it in our life (Four Arrows & Narvaez, 2022). Even if not possible with people, daily nature connection can mitigate the feelings of aloneness. Pets can help, but so can a plant, a tree we lean against, the sun on our skin, the earth on which we take a rest.

References

Four Arrows, & Narvaez, D. (in press, 2022). Restoring the kinship worldview: Indigenous voices introduce 28 precepts for rebalancing life on planet earth. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Gendreau, G. (2021). Jungle Jean: The life and times of Jean Liedloff, the woman who transformed modern parenting with The Continuum Concept. Precision House.

Liedloff, J. (1977). The Continuum Concept. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

Narvaez, D., Panksepp, J., Schore, A., & Gleason, T. (2013). Evolution, early experience and human development: From research to practice and policy. New York: Oxford.