Our “Science-Fictiony” Worldview Lens: Do We Ever Know What Is Happening?

An Interview With Marilyn Schlitz, PhD

About the Interview

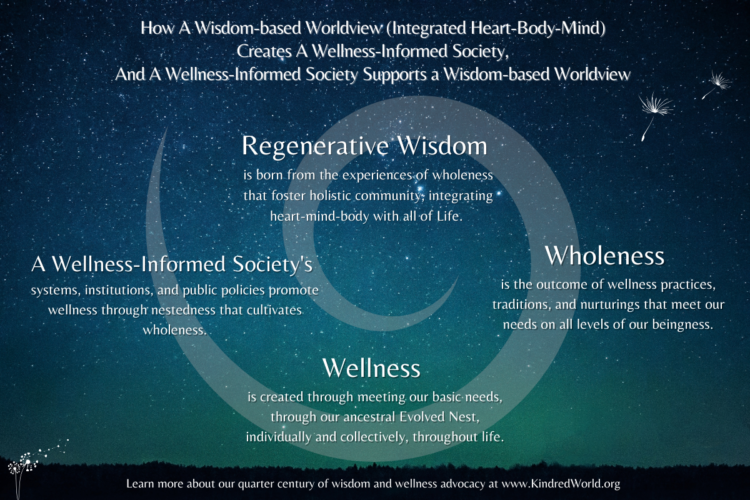

When it appears that everything is wrong with the world, we know we’re dealing with a worldview issue. Both science and wisdom traditions show us our worldview creates our world, but what creates our worldview?

In this interview, we will hear from Marilyn Schlitz, the social scientist and field-based researcher of human consciousness who will answer the questions, what is our worldview, how is it formed, and what does science show us about how to shift our worldview.

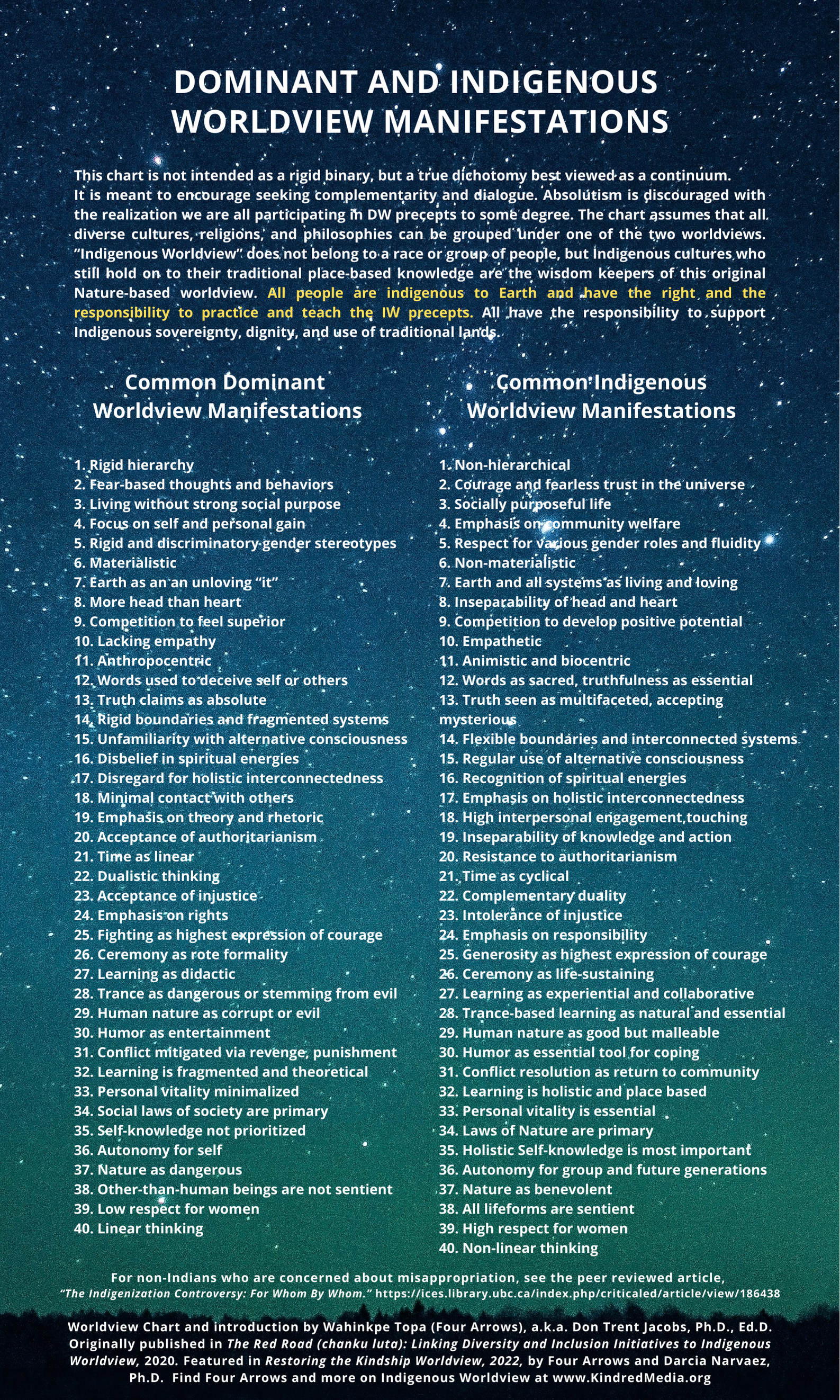

Kindred World’s nonprofit work and vision of a Wisdom-based, Wellness-informed Society has been supported by the Worldview Literacy facilitator training I received from Marilyn at the Institute of Noetic Sciences, IONS, over a decade ago (see the photo above). I include links below the podcast to resources for this program’s training, as well as the Kindred resources for our ongoing work with Four Arrows and Kindred World’s president, Darcia Narvaez, on Indigenous Worldview and Restoring the Kinship Worldview. As you will discover in the Worldview Chart below, cognitive anthropology, the study of worldview, and Four Arrows’ scholarly work in Restoring Our Kinship Worldview, reveals we only have two worldviews: a disconnected Dominant Culture worldview and our Indigenous Worldview.

Listen to the Interview on SoundCloud

Listen to the Interview on YouTube

About Marilyn Schlitz

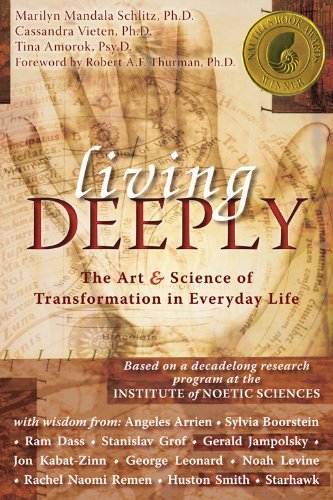

Marilyn Schlitz has conducted clinical, laboratory and field-based research into consciousness, human transformation, and healing. Her books include Living Deeply: The Art and Science of Transformation in Everyday Life; Consciousness and Healing: Integral Approaches to Mind Body Medicine; and Death Makes Life Possible (and companion film by same title). Having taught at Stanford, Harvard, and Trinity University, she is currently Professor of Transpersonal Psychology and President of the Academic Faculty at Sofia University, CEO/President Emeritus and Senior Fellow at the Institute of Noetic Sciences. Schlitz has published hundreds of articles in scholarly journals and popular publications, and has lectured extensively in diverse venues, including the United Nations, Smithsonian Institution, Commonwealth Club, and community groups across the world.

Our “Science-Fictiony” Worldview Lens: An Interview with Marilyn Schlitz, PhD

An Edited Excerpt of the Transcript is below.

Jump to these highlighted sections:

Worldviews Create Worlds, But What Creates Our Worldview?

Can We Discover Our Worldview? What Does Science Say?

Weapons of Mass Distraction and Other Worldview Awareness Challenges

Worldview Literacy: The Most Fundamental Skillset We Can Acquire

Finding Community: Shifting from Me to We Means You’re Mostly There!

Worldviews Create Worlds, But What Creates Our Worldview?

LISA: Welcome Marilyn. Thank you so much for coming.

MARILYN: Thank you, Lisa. Glad to be here.

LISA: We have some fascinating and important territory to cover on worldview today in this interview. You helped to create the Worldview Literacy program at the Institute of Noetic Sciences as the president and a researcher a few years ago and I was trained by you in the Worldview Literacy program as a facilitator in 2010. So, we’re going to help people understand this crucial term for our time and: how do we know what our worldview is and that we have one?

Can you just help us wade into that territory? I remember when we first started studying worldview literacy you introduced learning the difference between an opinion belief, and facts, and I thought, really? And now we’re in this post-truth, alternative-fact world, and that seems like a good place to start.

MARILYN: Well, that happened pretty fast and that’s kind of astonishing really, to think that we operate within these different bubbles. I think I would start with this distinction between ontology and epistemology. Those are big words, but our ontology is that basis of reality – what is so – and the epistemology is how we know what we know.

So, what are the different methods and means by which we try to understand the nature of reality? Understanding and navigating both our epistemology and our ontology becomes important because we can see that we can meet in a public sphere – maybe it’s a hospital or school system – and people are applying their energies to a shared goal, but they might be coming at it from very different epistemologies and ontologies. It’s almost like we’re moving through different realities together simultaneously, and it’s a little mind blowing and a little science fictiony and yet it is what is. So we are now at this time where we know that there are multiple cultures, there are multiple ways of engaging reality.

We have now achieved these remarkable accomplishments in terms of having an orbiting space station and all these great photos that we’re getting from these telescopes, looking at the depths of space. And we also know that this is a time of cloning. We can, in the course of a day in a Petri dish, really create new forms of life. And all of those are based in this kind of physical material model. There is a world out there and that is the reality. There is a world out there, and yet we know from our own beliefs and experiences that it might be a little more complicated than that. And so, how do we begin to think about not only that reality out there, but how there is a reality within here and that shapes how we’re able to perceive things. And so that’s what I would say is the basis of a worldview.

LISA: When you and I first worked together 10 or 12 years ago, and I encountered that first exercise in opinion, belief, or fact, that was just part of beginning to understand that it was possible to not know what territory you were in. As you said, this gets to be science fictiony and complicated, but we also learned about the multiple ways of knowing, our multiple intelligences. We don’t really talk about these capacities in our culture. But some of this insight starts to transform who we think we are as human beings. I think in a very exciting way.

So one question may seem remedial – about learning the difference between facts, opinions, and beliefs – but it seems so relevant right now, as we have January 6th committee hearings going on and the arguments taking up airspace over what is real, even if there’s a video to show us.

And this second question is, how do we know, as you were just pointing to, what else do we have to work with to know what is real with these multiple intelligences?

MARILYN: One of the really interesting things that’s emerged, I think, in the realm of cognitive psychology in the last 20 years, but more recently it’s come to the forefront, is the idea of our cognitive biases and the ways in which there are these filters. So, taking a step back and recognizing that our worldview is like a lens of perception through which we see the world. And it’s like, if you put on these glasses and suddenly maybe it’s like virtual reality glasses, suddenly you’re seeing things in a different way and engaging the world in a different form. Uh, and so what happens is our understanding of that world out there is shaped by our culture, our families, our education, our status in our lives, like the progression from being a small child to a senior citizen, all of those experiences move us through different lenses of perception.

So, our worldviews shift as we age, but there are these core metaphysical assumptions about what is true that can remain constant throughout our lives. And so, what you talked about as that objective world out there, really defines the materialist world we live in and it defines how we approach reality. If we think everything is material and physical, then the only ways we can know something is to touch it or taste it or measure it or manipulate it somehow. And yet, when you talk about these multiple ways of knowing, we’re also aware that our world, our worldview, can be informed by the nature of our intuitions. Is there something that we intuitively feel or our gut reactions and these things are very important, or are we visually oriented or auditorily oriented or is it about reading and writing for us?

All of those things influence what we determine to be facts. And I want to go back to this idea of these cognitive biases, because it’s really almost impossible to see the world as it is, or to experience the world as it is, because we have all these blockages. Maybe we make assumptions about a person’s skin color, and that then leads us to a very quick reaction about what we should think about that person. And maybe it’s about, you know, olfactory things. Sometimes there are foods that we really don’t like because they trigger associations that come from our old brain. All of those things influence how we perceive the world. And what I like to think about is this concept of worldview literacy, and basically the notion that we can learn about worldviews and we can teach about worldviews. There is a kind of literacy there that we can communicate to others. That’s really what I’ve been looking at over a series of decades now.

Can We Discover Our Worldview? What Does Science Say?

LISA: How do we learn about our worldview? If we’re in a protective mindset, our rigid authoritarian mindset, we may not have the capacity for self-reflection. What practices support us becoming aware of our mindset and then – this metacognition – of our worldview? How do we do that?

MARILYN: Yeah, I think it’s hard really. But I think, first of all, there is this basic awareness: “maybe I’m not seeing things in their entirety” and that comes with a kind of humility. So instead of having an arrogance and an assumption that I know everything, you know, stepping back and being a little bit cautious – a little bit more humble – and then recognizing that even if we feel like we have some mastery over our reactiveness we become this metacognitive capacity generator. We might then be in our cars going through traffic and somebody cuts us off. So, what’s the immediate reaction? That amygdala kicks in and we can become very arrogant. We can become very judgmental, and we can also become very aggressive. So, you know, road rage is something that people describe and that it’s all too familiar in this time and in this space that we live in.

So, the first thing is to slow down, to recognize that we have reactivities, and to begin to posit, like “what’s going on with that other person.” Maybe there is some kind of distress that we don’t know about. So, if you can come from this place of humility – and I actually like to think about something like road rage as a spiritual practice – it gives us an opportunity to check our own reactive tendencies, to take a deep breath. Breathing is so fundamental to a lot of these practices. And just position ourselves so that we can see things from the other person’s point of view. I think that’s just like the fundamental first step for all of us.

Weapons of Mass Distraction And Other Worldview Awareness Challenges

LISA: I remember hearing you speak about weapons of mass distraction in our culture. And we seem to have a lot stacked against us, culturally demanding our attention. What is the influence our culture is having on our worldview and the way it’s shaped right now?

MARILYN: Well, one thing we know is that information is accelerating. And in fact, the amount of information that we’re acquiring in the course of this day transcends everything that we we’ve acquired in the nature of human history. So, we’re bombarded by all these new factoids and experiences and images. You can think about the rate of commercials, for example, how much we’re bombarded by those. Even if we think we’re not, we go shopping and there are all these billboards and the front stand that pulls our attention. Recognizing that our attention and our motivations drive where we place our focus becomes important. Recognizing that we’re bombarded by all this new information coming at us at an accelerated pace can be absolutely overwhelming. And it’s very difficult in that context to center and to begin to understand what is our authentic perception? What is it that is true for us? And to begin calibrate that epistemology, “How am I knowing what is true when there’s so much stuff coming at me?”

And how can I begin to calibrate that?

This idea of learning is very, very challenging because we have all these biases and we have this amygdala brain that blocks our capacity to move into the prefrontal cortex. Our brain is both very reactive and very contemplative. We have an ability to pull back and that’s that metacognitive thing you’re talking about. It’s like this larger way in which we can begin to see what’s forming our opinions, what we are able to constitute as facts for ourself and how our worldview – that lens of perception – influences all of that.

So again, I go back to humility and the idea that we can slow down and sometimes we know things because our life experience gives us that information. So those can be very fastly calibrated, but there’s often the case where we’re forming opinions out of previous experiences that are not relevant to our current experience. And so how can we just pause long enough to reflect on that? So those are a couple of the basic, foundational steps to begin to understand worldview and to begin to understand how we can become more aware of what we’re not aware of.

Worldview Literacy: The Most Fundamental Skillset We Can Acquire

LISA: Richard Tarnas has said, worldviews create worlds. How critical is this understanding that we have a worldview?

MARILYN: I think it is the most fundamental skill set that we can acquire. And then the question is, “How do we break out of our steady state if we are living in this ontological bubble and we aren’t able to move beyond it.” The bubble is containing us and that can lead us to make missteps along the way, to assume that the world is something other than what it is, because we’re trying to shape that world based on our own assumptions, our beliefs, our previous experiences, the life we’ve grown up in. My own work has been to understand the nature of worldviews and to look at that from a variety of different cultural, religious, spiritual, and academic perspectives. In order to broaden my own worldview, I really appreciate the concept of curiosity and this notion of a growth mindset.

How can we cultivate the capacity to move out of our ontological bubble to recognize that there are these multiple epistemologies and ways of knowing about the world and in that process, we can be imbued with a greater appreciation for all the pluralistic ways in which we can engage reality? I worked with a team and we explored the nature of this worldview literacy concept by looking at how it is that people can break out. What are the facilitating factors that allow people to begin to see things in a different way and to bring about this kind of humility?

We did this through interviews with 60 masters from different world traditions (see the book Living Deeply: The Art and Science of Transformation in Every Day Life). We interviewed them in a very systematic way. We had a team of people who were coding the transcripts and interviews so that we could come up with themes across these different traditions.

The very first question is, how do we shift our worldview? How do we broaden our worldview? And again, it’s really hard. This is not a simple task. It requires discipline, effort, motivation, all of these things. And sometimes it can happen very quickly that we have some kind of experience that disrupts that steady state. Maybe it’s the death of a loved one or the loss of a job, a personal illness. Maybe it’s something ecstatic, maybe it’s some kind of out of body experience or perhaps a near death experience, perhaps a kind of ecstasy experience. People are talking about the Overview Effect now where these astronauts come back from space and begin to see the world in a different way. How can we wake people up without having to go walk on the moon in order to have these experiences?

The first thing is to recognize that there are these difficulties that present themself in our life, even catastrophic things that can really make us feel disempowered. And yet through the lens of worldview, we can begin to see these as opportunities. They are disruptions from something that limits our capacity to see. So, once we can begin to stand back and look at what are often very negative things in our life. And we can begin to see that this is an opportunity for us to engage in a new way in with a different perspective. So that was kind of the first thing.

And then, people can have these shifts in worldview or these Eureka moments, or something that really feels disruptive and then they can go right back to their steady states. Because again, there are these cognitive biases that limit our capacity to change.

It takes effort then to begin to broaden out of, and to become curious about, the potentials. That cultivating of curiosity and our wanting to explore, wanting to be in some kind of adventurous process becomes the second stage of this, where we become seekers. And the pitfall of that is, that we can get into this endless loop of forever seeking. And then we haven’t really grounded ourselves, and we don’t feel that sense of stability.

So how do we begin to move toward what can be very destabilizing if we have always thought the world was this way, and suddenly we’re seeing it as something different? That can be hard. People then are encouraged – based on our interviews and ultimately then 2000 surveys that we did – people can begin to take on a practice. And that allows us to engage in something that gives us support in the midst of this destabilization.

Getting Rooted With Practices: The Five Elements

MARILYN: So what is a practice? I mean, people described all kinds of things as a transformative practice that really helped them to engage this expanded worldview. And, there were five elements we identified in the course of looking at a transformative practice, whether it was somebody sitting in a meditation or gardening or running, or spending time in nature, all of those things can become a practice if we bring these five qualities to it.

The first thing is intention. I bring the intention to foster a worldview that allows me to see things from a broader perspective and also to become more stable in my own ability to grapple with all these weapons of mass distraction that you talked about. So, intention becomes extremely important. And yet we know that they say the road to hell is paved with good intention. And how many of us set New Year’s resolutions? And then a day, a week, a month later, we’ve forgotten we even did that. So, intention alone isn’t enough, but it is a necessary prerequisite.

The second step is attention and where are we placing our attention? Is it on the glass half empty or the glass half full? And becoming aware that we can choose that becomes really important. This goes back to the idea of these cognitive biases. If we’re operating on autopilot and all these influences are affecting us, and we’re driven by the materialist impulses that society is pulling us toward, it becomes very difficult. But once we can recognize that, first of all, we have these biases and that in order to see past them, we need to slow down and train our attention so that we can begin to perceive the multiplicities of how we know what we know: our epistemologies and ultimately the ontologies, because there may well be more than one absolute reality. It may be that absolute reality is made up of this multiplicity of views and facts and perspectives and assumptions.

The third piece is to have some kind of routine. How do we begin to train our brain and our bodies and our awarenesses to stay awake and to be informed? How do we do that? And so, building new muscles, just like we’d go to a gym and we’d work out. We can begin to train these neural pathways in our brains and to recognize the plasticity that allows us to begin to perceive in new ways.

The fourth piece is consistent across all of the masters that we interviewed, and that is guidance. It’s not really easy to do this stuff on our own. How is it that we begin to recognize that there are people who have been on this path before us? Maybe it comes from a book or maybe it comes from a podcast, or maybe it comes from sitting with a teacher. All of those things can offer us a kind of guidance.

It’s also clear that it’s not only guidance that comes from outside of ourselves, there’s this inner guidance. And so, as we can begin to calibrate our own intuitions and the multiple ways in which we learn, and we can begin to see things with a kind of imbued nature. This becomes a kind of internal guidance system that is that north star that propels us or that golden thread that pulls us.

And finally, there is this concept of surrender. This is particularly true when we think about change and we want to be change makers: sometimes things are happening in the world that we can’t influence, and maybe it requires just stepping back and appraising what is so and surrendering to the idea that there are pieces of this puzzle we can begin to affect change in, and there are places that we can’t.

And so, to release ourselves from the burden of thinking that we can fix it all, and that there’s just this magic wand that we can wave. And then this model that we created, really involves this shift from the me to the we. But if it’s all about the we, then we can forget about the me, and that’s where you talked about burnout.

So, how can we cultivate these skills to nurture ourselves, even in the midst of enormous complexities? So just breathing or centering, taking a walk in nature and really appreciating what’s around us, practicing gratitude, all of these become wonderful tools for nurturing our own inner life.

And then finally, I think this process can be like a fractal and we can amplify it in the world through the various institutions. Whether it’s business or science or education or community organizing, all of that can be informed by recognizing that the catalyst of change come from inside us and give us the capacity to be strong and facile and agile in the face of these enormous changes that we’re dealing with. And that we can begin to apply these kinds of insights into those dominant institutions and recognizing that it’s not really possible to do this alone. And so, reaching out and finding those communities that may not all look like us may be informed by different epistemologies and ontologies, but together with that kind of curious mindset, we can begin to affect positive changes.

Finding Community: The Shift From Me To We Means You’re Already There

LISA: Marilyn, that was just glorious. Thank you so much. That was just fantastic. I do remember in our Worldview Literacy class, one of the pieces that you just now touched on was the community piece. And I know in America, isolation, loneliness, especially among young people, um, is epidemic right there with addiction and depression. I do remember one of the change models from IONS, how do you make something stick? How do you make a change stick for yourself? And it seemed like people who were able to go to a space of like-minded people and just be together, that really helped. Can you speak to community for a moment?

MARILYN: I think sometimes when we experience a shift in worldview that allows this more complex, multifaceted reality, it can feel very lonely. We can feel like we’re the only ones and we’re oddballs. And we don’t have a Songa, a community to rely on. The one thing I would say is that I don’t think the kind of community that is most effective is just everybody being like us. It’s really fostering the skills for being with people who may be different from ourselves and knowing that we have this capacity to see and to communicate and to engage with people who are different from ourselves. I do think it’s true what you said. People have to get off the pillow or get out of the pew and into the world and move together with a group who can represent our tribe, our emerging tribe, a tribe that is of this mindset that we want to see past the biases.

We want to see past the cultural limitations and begin to craft something that is more sustainable and nurturing to the livelihood of all creatures on this planet.

RESOURCES

Learn more about worldview on Kindred.

Learn more about our Indigenous Worldview.

Read the introduction to the book, Restoring the Kinship Worldview.

Download a PDF or JPEG of Kindred’s Worldview Chart by Four Arrows here.

Visit Marilyn Schlitz’s website to discover her worldview class.

Visit the Institute of Noetic Sciences.