The Continuum Concept, A Book Review

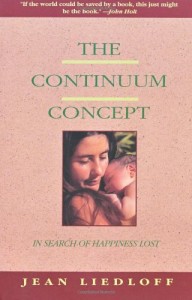

The Continuum Concept: In Search Of Happiness Lost

A Book Review By Meryn Callander

Jean Liedloff, author of The Continuum Concept, spent several years with the people of the Yequana and Sanema tribes of South America. They were the happiest people she had ever seen. The children never fought, were never punished, and obeyed happily and instantly. Her western perceptions of human nature totally demolished, she emerged with a radical understanding of our deepest needs and potentialities for wellbeing–and of the means through which we may begin to heal ourselves and save our children.

Most crucial is the cognition that the way we treat our very young is a primary cause of the alienation, neuroses, and unhappiness that is normative in the civilized worlds. The infant’s early experiences influence all that he becomes. The growth of independence and emotional maturity spring largely from the in-arms phase of life outside of the womb, i.e., the phase prior to the commencement of crawling.

In “continuum-correct” cultures, the infant’s experiences correspond to his and his mother’s ancient expectations. Mother and child remain in close contact from the moment he emerges from the womb. The umbilical cord is not cut until it ceases to pulsate. The infant is given the breast. This is the moment of “imprinting.” Geared into “the sequence of hormonally triggered events at birth,” it must take place right away. The urge is immediate, and, Liedloff asserts, its satisfaction an essential prerequisite to the smooth succession of stimuli and responses that follow as mother and baby begin their life together. The infant seldom has any need to signal by crying, or do anything but suckle when the impulse arises. At night, mother sleeps beside him. The infant is taken everywhere, always in-arms, and is there in the midst of an active person’s life. He enjoys occasional direct attention, but his main business is to absorb all the actions, interactions, and surroundings of his caretaker. This information prepares him to take his place among his people.

What this infant experiences is congruent with his continuum sense–his deepest expectations. These species-specific expectations have evolved through millennia as being most appropriate to fulfill his needs and contribute correctly to his development. Having received, in full measure, the shelter and stimulus of his experience in-arms, he feels right, good, and welcome. He can look forward, outward to the world beyond mother, sure of himself and accustomed to a condition of wellbeing that his nature tends to maintain.

For millions of years newborn babies have been held close to their mothers from the moment of birth. Some babies of the last few hundred generations may have been deprived of this experience but that has not lessened each new baby’s expectation that he will be held in his rightful place.

The expectations of the newborn in our “civilized” world are identical with those in continuum cultures. He has come prepared for the massive leap from womb to arms, but not for what follows. The following two paragraphs are a precis of Liedloff’s vivid–and, unfortunately, all too accurate–description of the experience of the typical newborn in our culture:

Skin crying out for the touch of living flesh, he is wrapped in a dry lifeless cloth. Every nerve ending under his newly exposed skin craves the expected embrace. He is put in a box where he is left, no matter how he weeps, in a limbo that is utterly motionless, utterly lifeless. He cries and cries; his lungs are strained with the desperation in his heart. No one comes. All he can do is to cry on. He falls asleep, exhausted. He wakes in terror of the silence and motionless. He screams. He is afire from head to foot with want, with desire. He gasps for breath and screams until his chest aches. His throat is sore, the sobs weaken, nothing helps. He stops, able to suffer, unable to think, unable to hope. His continuum has no solution for this extremity. The situation is beyond its vast experience. He has already reached a point of disorientation from his nature beyond the saving powers of the continuum.

The tearing apart of the mother-child continuum results in agony for the infant, and depression for the mother, deprived of what “nature had her exquisitely primed for… one of the deepest and most influential emotional events of her life.” And, one which would have encouraged her to continue to behave as is most rewarding for herself and her baby.

We are disengaged from our continuum at birth. Left in cribs and baby carriages, away from the stream of life, and starving for contact and in-arms experience, we go on, in an orderly but unconscious way, seeking fulfillment of those expectations. Deprived of the essential condition of wellbeing that should have grown out of this time, searches and substitutions for it, as the years pass, take on a great many forms.

Liedloff contrasts the ways of the western world with those attitudes and practices of the Yequana which serve to maintain the state of wellbeing that is evident among their people. For example, the attitude of caretaker to the young in continuum cultures is relaxed, usually attentive to some other occupation, but receptive at all time to his approach. It is the baby who seeks her out and indicates what he wants. She complies, but adds no more. He neither demands nor receives her full attention, for “he has no store of longings, no ancient hungers.” The need for constant contact tapers off quickly when its quota has been filled.

With the commencement of crawling, the child is naturally protective of his own wellbeing, expected to be so by his people, and enabled to be so by his inborn abilities, stage of development, and experience. There are many potentially dangerous situations among the Yequana–from the machetes left lying about, to the hazards of the jungle: injuring one’s bare feet, snakes and scorpions, and rivers the children bathe in. Yet there are virtually no injuries. The operative factor, Liedloff has determined, seems to be the placement of responsibility. In most western children, the machinery for looking after themselves is in only partial use, the burden being largely assumed by caretakers.

The keystone upon which the tribal child’s development depends is the assumption that he is innately social in his motives; his persona is respected as good. There is no concept of a “bad” child. This assumption is “at direct odds with the nearly universal civilized belief that a child’s impulses need to be curbed in order to make him social.”

Furthermore, in these societies, respect is accorded each individual as his own proprietor. Liedloff found that no orders are given a child that run counter to his own inclinations as to how to play, what to eat, when to sleep etc.; but when his help is required he is expected to comply immediately. Social animal that he is, he does as he is expected without hesitation and to the best of his ability. Praise, virtually absent in these cultures, wreaks havoc in ours. “Oh what a good girl!” implies sociability is unexpected, uncharacteristic, and unusual–and a child does what he perceives is expected of him, rather than what he is told to do.

Liedloff asserts that while it is unrealistic to describe a culture to which ours could be changed, there is value in tracking down some of the qualities a culture would need to suit the continua of its people. To list but a few: we would see families in close contact with other families, generations living under the same roof, and babies carried everywhere. Children would accompany adults on their daily rounds: “It is only a matter of changing one’s baby-centered thought patterns to those more suitable for a capable, intelligent being whose nature it is to enjoy work and the companionship of adults.” The relationship of educators to children would be based on being available, and children using their own efficient, natural way of educating themselves. We would recognize the human need for contact, break through our cultural taboo on touch, and change the view that we own our children and consequently treat them as we like. Leadership would emerge naturally and confine itself to taking initiative only when individual initiatives are impractical.

Without waiting to change society at all, we can behave differently toward our infants, and give them a sound personal base from which to deal with whatever situations they meet.

Liedloff urges constant physical contact until children begin crawling, sleeping with them until they leave the family bed of their own accord, meeting their innate expectations, not overprotecting them, and trusting and respecting their developing personalities.

Liedloff acknowledges that at this moment in our history, with customs as they are, continuum principles seem wildly radical things to advocate. “But in the light of the continuum and its millions of years, it is only our tiny history which appears radical in its departures from the long-established norms of human and prehuman experience.”

And, we have nature on our side.

…[O]nce a mother begins to serve her baby’s continuum (and thus her own as a mother), the culturally confused instinct in her will reassert itself and reconnect her natural motives. She will not want to put her baby down… the ancient instinct will soon take over; for the continuum is a powerful force and never ceases to try to reinstate itself. The sense of rightness felt by the mother when she is behaving in accordance with nature will do far more to reestablish the continuum in her than anything this book may have conveyed to her as theory.

I can only close with a resounding “yes!” This has proven to be unqualifiedly true for me. I have shared a little of my experience with this book in my cover letter. It will come as no surprise then, that I consider it an absolute must read.

We sponsored Liedloff to lead a day-long workshop in Mendocino County, where we were living when Siena was very young. Apart from affording us the privilege of coming face-to-face with Liedloff, who is a colorful character–forthright, provocative, entertaining–this provided us with the opportunity to hear her responses to a host of questions on the day-to-day implementation of continuum principles, and keyed us into a circle of parents who shared our interests in implementing this material.

The Liedloff Continuum Network is a worldwide network of people interested in making the Continuum Concept a part of their lives.

Featured Photo Shutterstock/Alina Reynbakh