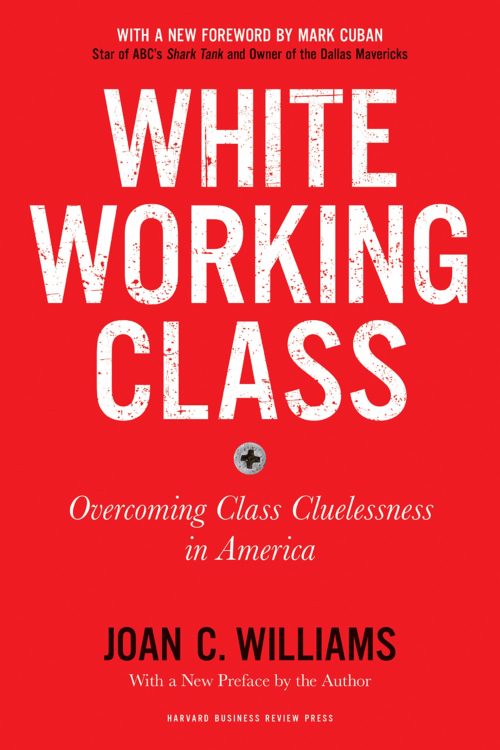

An Interview with Joan C. Williams, founder of the University of California at Hastings’ Center for Worklife Law and author of White Working Class: Overcoming Class Cluelessness in America

![]()

The Center for Worklife Law’s group photo of the Breastfeeding Policy Summit attendees. August 2019.

![]()

![]()

Class Conflict, Breastfeeding Policy and Systemic Change: An Interview with Joan Williams

Kindred’s editor, Lisa Reagan, attended the University of California at Hastings’ Center for Worklife Law‘s Breastfeeding Policy Summit at Jones Day Law Firm in San Francisco on August 6, 2019 (see photos above). The summit’s purpose was to educate an invited group of activists from around the country on the insights gleaned from Joan Williams’ quarter century research into advancing women in the workplace, as well as the center’s new reports on discrimination against breastfeeding and pregnant mothers in the workplace. The summit trained activists in choosing politically-conscientious verbiage, becoming aware of values of their legislators and region, and using these insights to help create and pass legislation to promote and protect women’s reproductive rights in the workplace.

Joan C. Williams is a Distinguished Law Professor and Founding Director of the Center for WorkLife Law at UC Hastings. Her path-breaking work helped create modern workplace flexibility policies and the field of work-family studies. She has authored over 90 academic articles and 11 books, including White Working Class: Overcoming Class Cluelessness in America and What Works for Women at Work. One of her proudest accomplishments was winning the Betty Crocker Homemaker Award in high school.

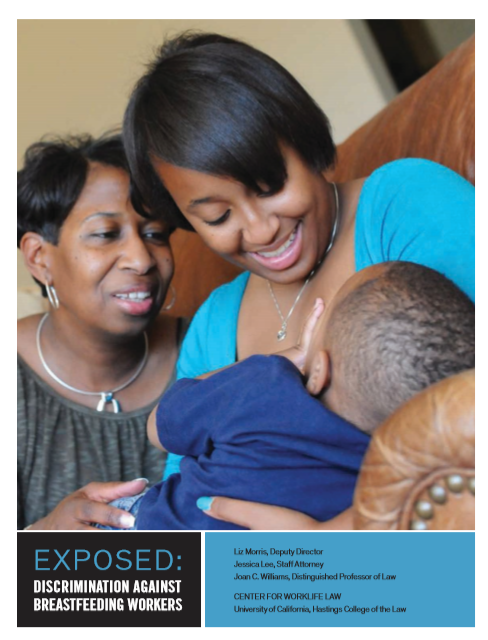

For an overview of the issues surrounding workplace breastfeeding as a human reproduction right, read the center’s new report, Exposed: Discrimination Against Breastfeeding Workers.

Read more about Joan Williams below, listen to the interview, and follow along with the transcript.

About Joan C. Williams

Described as having “something approaching rock star status” in her field by The New York Times Magazine, Joan C. Williams has played a central role in reshaping the conversation about work, gender, and class over the past quarter century. Williams is a Distinguished Professor of Law, Hastings Foundation Chair, and Founding Director of the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California, Hastings College of the Law. Williams’ path-breaking work helped create the field of work-family studies and modern workplace flexibility policies.

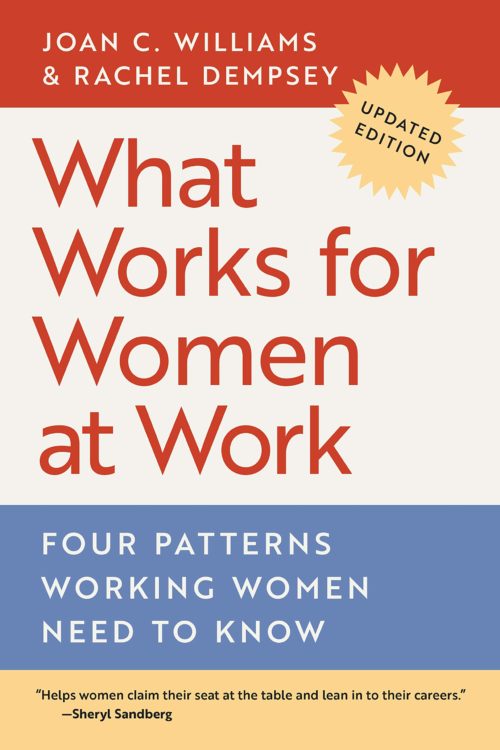

Williams’ 2014 book What Works for Women at Work (co-written with daughter Rachel Dempsey) was praised by The New York Times Book Review: “Deftly combining sociological research with a more casual narrative style, What Works for Women at Work offers unabashedly straightforward advice in a how-to primer for ambitious women.” Following its success, Sheryl Sandberg and LeanIn.org asked Joan to create short videos sharing the strategies discussed in the book. The videos have been downloaded over 975,000 times and are featured by Virgin Airlines as in-flight entertainment, seen literally around the world. Most recently, Williams co-authored a workbook companion to What Works for Women at Work, available now from NYU Press.

Williams is one of the 10 most cited scholars in her field. She has authored 11 books, over 90 academic articles, and her work has been covered in publications from Oprah Magazine to The Atlantic. Her awards include the Families and Work Institute’s Work Life Legacy Award (2014), the American Bar Foundation’s Outstanding Scholar Award (2012), and the ABA’s Margaret Brent Women Award for Lawyers of Achievement (2006). In 2008, she gave the Massey Lectures in the History of American Civilization at Harvard. Her Harvard Business Review article, “What So Many People Don’t Get About the U.S. Working Class” has been read over 3.7 million times and is now the most read article in HBR’s 90-plus year history.

TRANSCRIPT: An Interview with Joan C. Williams, an edited transcript from the podcast interview above.

LISA REAGAN: Welcome to Kindred. This is Lisa Reagan and today I am talking with Joan C. Williams, founding director of the University of California at Hastings Center for WorkLife Law. She is also the author of numerous books that have reshaped the debates over women’s advancement of the past quarter century.

Her scholarly research has documented workplace bias against mothers, organized social scientists to track workplace bias, and exposed how the work-family conflict effects working class families through reports such as One Sick Child Away from Being Fired. The Center’s recent report, Exposed Discrimination Against Breastfeeding Workers, can be found on Kindred.

I talked with Joan this summer at the Center for WorkLife Law’s Breastfeeding Policy Summit in San Francisco. The summit presented a refined set of insights and tools for an invited group of activists to take back to their states and organizations. The tools from this summit enabled activists to understand how public policy and law can be shaped and pushed through in their states’ legal system. This summit offered sophisticated tools for creating the systemic change America needs desperately at this time. So, welcome, Joan.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Delighted to be here, Lisa. Thanks for the invitation.

LISA REAGAN: I know we both have colds, so, as we said before we started recording: we are activists, we are going to push through, and there that is.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Yeah. Exactly.

Toxic Masculinity as an Obstacle to Breastfeeding Policy

LISA REAGAN: I would like to start by introducng Kindred followers to your tremendous body of work, which provides a different context for looking at breastfeeding issues in the United States. I really encourage listeners to read Joan’s publications about the working family and the work-life conflict. There is a tremendous amount of material and insights that we’re not going to be able to cover in the next forty minutes. (See links to Joan’s work and videos at the end of this transcript.)

I would like start with your research-based belief that the work-family conflict isn’t really about women, it’s about men and toxic masculinity.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Yeah, I mean we tend to associate work-family conflict with women because they are kind of on the front lines, but it really goes back to how we define the ideal worker and in far too many workplaces today, we still define the ideal worker as someone who takes no time off for childbirth, no time off for family caregiving and no time for breastfeeding. Who does that describe? You know, it certainly does not describe most women. It describes someone with a man’s body and men’s traditional life patterns and even one of the things that we’ve seen over the past since I’ve been working on this issue for nearly 40 years.

One of the things that’s really dramatic is that there’s been a shift among younger men in what they see as being a good father. Men in my generation, I’m in my 60s, thought that they were great fathers because they changed a diaper. But younger men really are kind of where my generation of mothers were, many of them. They see being a good parent is involving daily care of children and they’re willing to take some career hits to accomplish that, but there’s another group of men, many of them older, some of them equally young, who just don’t see that as being a good father, they see that as being an ineffective breadwinner and an ineffective man. So this is really a conflict among men in the workplace, by people who have defined their lives by being that ideal worker. They see that as the only way to be a real man and an effective person. They are really what is blocking change.

Class Cluelessness, Class Conflict and Culture Wars

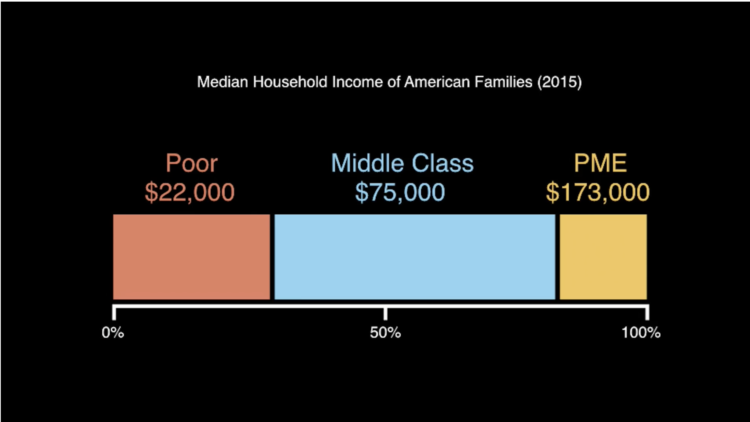

LISA REAGAN: And then there are the class conflicts and cluelessness that you explore in your work. When we are talking about professional managerial elite, when they hear the phrase “working class,” they think of the poor, when actually we are talking about most of Americans in the middle. Is that right, Joan?

JOAN WILLIAMS: Well, there’s really, for purposes of analyzing politics and social policy in the United States, I really think we need to think about three different groups. One are low income people with the bottom 30% of Americans by household income with an annual household income of around $22,000. That’s the poor. Then the professionals are really the top 16-20%. They have an average annual income of about $175,000. Then there’s that 50% of Americans in the middle. They’re called the middle class, sometimes they’re called working class, but they’re the middle 53% and they have a median annual income of around $75,000. There are conflicts between the elite and the middle are driving, for example, Trumpian politics. And the conflicts between those two groups also are what have made it really impossible to pass at a federal level effective legislation to reconcile a working family in the way that has been done in most other industrialized countries.

LISA REAGAN: To bring those two issues together, class conflict and toxic masculinity, your work shows this idea of being a breadwinner in an economy that has continued to deteriorate in the last couple of generations is a lethal ideology for men.

JOAN WILLIAMS: It’s not a healthy ideology for men. More generally, the ethic of overwork that’s built into that conception of the ideal worker leads to higher healthcare prices as well as family prices. But one of the things that we see in the United States because of the growing inequality of income is that it used to be that blue-collar men and white-collar men could perform as ideal workers. That is much less so now with the withering of good, solid blue-collar jobs and the alternative to those ideal worker jobs, blue and white collar, has increasingly become muck jobs where you have to scramble to get enough hours.

We’ve done a huge study talking about how people’s schedules are often so unstable that they’re given part time hours and they have no idea when those part time hours are going to be from week to week. That obviously puts people literally at risk of losing their children, or losing their job, because if they don’t show up to their job, which they just found out two hours ago that they have to show up to, then they’re going to lose their job, but if they leave young children home alone, then they might well lose their children. So, a lot of Americans, certainly among that bottom 30%, but increasingly even Americans in the middle, are in that kind of situation, and not too surprisingly, they’re fit to be tied. They’re very angry about it.

LISA REAGAN: And what are they doing with that anger?

JOAN WILLIAMS: Well, unfortunately, they’re not doing anything very effective with that anger right now. That anger has been kind of sculpted as anger towards elites which has been expressed and anger towards kind of professionals, professors, those are the thorns of the world, rather than focusing the anger on the people who are designing those jobs in that exploitative way in the first place. That’s the political challenge of economic populism, and race is definitely a big factor there.

Many of the people – both on the bottom and in the middle – if they’re white, they’re interpreting the fact that they no longer see a path to a stable middle class life, they interpret that through the lens of race, that it is because they are white people, instead of interpreting it through the lens of class, that it is because they are working class people, which in my view, is actually what is going on.

Bridging the Class Culture Gap

LISA REAGAN: So when we were in California, I found out that you had written the most read article in the Harvard Business Review ever and the title of that is, “What so many people don’t get about the US working class.” In that article, and then the book, White Working Class, Overcoming Class Cluelessness in America, you say it is dangerous that there is so much cluelessness between classes. What is needs to happen to bridge the gap?

JOAN WILLIAMS: What people need to understand is that the key class conflict that’s driving economic populism, and this is as true in Europe as it is in the United States – the book has had a big reception in Europe – is that middle 53%, not the poor, but the middle 53% who have seen their incomes and the solidity of their lives really threatened by globalization and accompanying economic changes, that group is very different culturally and economically from what I call the professional managerial elite, that top 16-20%, who also in the United States call themselves middle class. So, it is extremely confusing. But there is really what I call a class culture gap between those two groups that is largely shared across race, although there is one important difference that I will mention.

The professional managerial elite, they’re very focused on self-development, because that’s what helps them get and keep good jobs. They’re very focused on displaying sophistication because that’s what marks them as a member of that elite. So, there are very specific emotion rules as to who you are supposed to be empathetic with, and who you’re supposed to be judgmental of. You are empathetic with the people who produce jazz. You’re judgmental of the people who have pink flamingos on their lawns. So, there’s a very specific class and race set of emotion rules in the elite.

There is also a set of class commitments and emotion roles in the middle class and that context, and this is true across race. People are less focused on self-development than they are on self-discipline, the kind that gets you up and to work every day to a not very glorious job without an attitude. That takes a lot of self discipline.

So, people in the middle are very respectful of self-discipline and the institutions that traditionally aid self-discipline: the church, the military, family values. And so you have this class culture gap between the elite which is very focused on the edgy, whether it is edgy dressing, edgy language, edgy sexuality to show their sophistication and the people in the middle of all races that are very focused on traditional institutions and the self-discipline that they aid. That’s the class culture gap that is driving American, and I must say, European politics.

The condescension of the professional managerial elite towards people in the middle and their bad taste, their lack of sophistication, it is really fueling a lot of political fury. The best example among the elite people is they have understood that they need to run class condescension through their head if it is class condescension to people of color – because they are very focused on race. They are not focused at all on class in the professional managerial elite because class doesn’t exist, they just are where they are because they’re the smartest people, not because they started with a silver spoon and now have a platinum spoon. So, it is far easier for them to admit the existence of racial privilege then it is to admit the existence of class privilege and that’s kind of the essence of class cluelessness.

They are not focused at all on class in the professional managerial elite because class doesn’t exist, they just are where they are because they’re the smartest people, not because they started with a silver spoon and now have a platinum spoon. So, it is far easier for them to admit the existence of racial privilege then it is to admit the existence of class privilege and that’s kind of the essence of class cluelessness.

Feminism and Worklife Law

LISA REAGAN: Just to clue in our listeners again, what we’re doing is mapping out the context of what’s really in front of us as we turn towards this breastfeeding policy summit and the takeaways from that glorious meeting that you sponsored in August of this year. Right before we go there, I would like for you to map out the connection between feminism and worklife law.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Well, I mean, I actually think of myself as a scholar of social inequality. I started out in feminism because that’s the dimension of social inequality that affected me, being born basically as a privileged white woman. But then I realized that I was interested not just in feminism as traditionally defined, but I was really interested on how the configuration and gender bias, but how gender bias differs by race. Because gender bias is a very racialized phenomenon, so basically, white women definitely encounter it, but they encounter it in somewhat different ways than the way women of other racial groups encounter it.

For example, if a white woman is too dominant, she is written off as a witch. If an Asian American is, she may be written off as a dragon lady, and in my doing interviews of Latinx women, they may be called feisty or sassy. Those are, at some level, is that nuance? I don’t think so. There are some very important differences that are embedded there. So, kind of the second step was to try to understand how the experience of gender bias differs by race. The third step was to understand the differences and divergences between gender bias and racial bias because one of those…

For example, there are four basic patterns of bias. Three of them are triggered both by gender and by race. For example, one of them I call Prove It Again, and that’s that some groups have to prove themselves more than others. Our research shows that is very true. It is true in today’s workplace and the group that ports the highest level of that Prove It again bias is women of color. So, I’m very interested in these different vectors of social inequality. I have been talking about class as well and how they interact. Sorry, I guess that’s pretty abstract.

LISA REAGAN: Well, I read an interview where you were saying that you saw feminism as being divided into at least three distinctive and overlapping pursuits and one was the work-family, which is what we’re in now.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Yes. Yeah, I see feminism as being divided into a kind of what I call the work-family axis, which is the subject of this interview. And then there’s the sex-violence access, which includes things like race and sexual harassment, all of the ways that sex and violence intertwine and then there are other axis as well. The third major is what I call a queer axis and that has to do with the conventional alignment of how you dress, for example, and the shape of your body and your reproductive function.

Worklife Law and Breastfeeding Policy

LISA REAGAN: Okay. So at the Center for WorkLife Law, which you are the founder of, how did your work take you there, and then I would just like to go into the breastfeeding policy summit and some questions about that day we spent together with so many presenters who gave us very sophisticated tools for making change for when we returned home.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Yeah, I mean, I had my first child in 1986 and at that point, I got really hot under the collar because I realized that the way the world is set up is pretty much designed to marginalize mothers economically and a society that marginalizes its mothers impoverishes its children, which is what we have – as I have mentioned children are the poorest group in the United States.

If you look, if you compare women to men, and you include people who work part time, which of course many mothers do, mothers still make 59 cents on the dollar that fathers make. So, we’ve seen really very, very, little progress. The research shows that the motherhood penalty, the penalty that women encounter economically when they have children, now accounts for an increasing proportion of the gender gap.

I founded WorkLife Law basically to say, we’ve got to make the world safe for mothers because the way we organize work and family now is bad for women. It is in many ways, worse for men as we’ve talked about. They kind of get stuck in these toxic ideal worker scripts and, of course, it is worse for children, because, again, a society that marginalizes its mothers, impoverishes its children, and we set aside mothers as the group that is charged with championing children and then we make them very economically vulnerable and very socially belittled. This is a terrible idea.

One of the first things I said is that because people were openly discriminating against mothers, and federal courts were saying that is not sex discrimination, we have got to turn that around, that is sex discrimination. Now people recognize it as sex discrimination, and it is recognized in courts as sex discrimination.

Then another thing that we did at WorkLife Law is we were part of the generation that crystallized flexible work arrangements, including quality part-time work. That was not completely successful, but it was far more successful than before. Because when you think about it, if you were redesigning that ideal worker with children, most adult workers have to both support the children and help care for the children. That’s the reality on the ground and for many, many people, that’s their ideal too. They want to contribute to their children in two different ways. That’s far better for children because you have both partners invested in the children and not just the partner who is really invested, economically very vulnerable, and a lot less powerful in the relationship.

Species Typical Baselines for Optimal Wellness

LISA REAGAN: So before we started recording, we talked about the baselines for species typical optimum health, a phrase that is better to use when describing family wellness, especially in the last 15 years of presenting to groups and for some reason, especially in California. When I talked about family wellness and babies and where does health begin, I was really conducting field research into the wellness paradigm and asking where is that in this culture? How do we get to that place? What I realized is, when I said words like mother, baby, family, fathers, the audience would start recoiling. So, I started monitoring my language and altering it to more more neutral terms and to just really try out this very basic science that is missing from a lot of our public policy, which are the baselines for health that do begin prenatally. You had a wonderful response to that, just clarify again for me, why is this baseline for wellness, especially in infants and for mothers, missing?

JOAN WILLIAMS: Well, it is missing in the US, because we kind of don’t do social subsidies. So, the traditional conception in the US is that having a child is kind of like a private frolic, kind of like hang gliding. I don’t finance your hang gliding, why should you finance my child? You think about that and when you kind of run it through your head, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. I mean, the reason I should help finance your child is because that’s the next generation of citizens. That’s the only way we have a country going forward.

At a more concrete level, when I’m in my 90s, God willing, and I need a doctor to take care of me, it is going to be someone’s kid who is that doctor. But Americans, again, they kind of erase all of that and they think having children is something that is like kind of a private affair that has no implications for spreading the costs and they typically privatize the cost of childrearing on the individual mothers. That’s a terrible idea and it is not one that is going to deliver either the health of the nation, or as you pointed out, the health of the individuals in it.

LISA REAGAN: Right. Nadine Burke Harris is now the surgeon general of California and she is a champion for ACES, the adverse childhood events study, that was done originally by Kaiser Permanente back in 1979 and is just now coming out to show stressors and adverse childhood events, trauma, are predictors of adult illness. With ACES we can test children early to see what have they already been exposed to and then use trauma-informed care, TIC, to recover. We can tell if a population is going to be a healthy population or is this going to be a sick population. Why should I spend my money on your child? Well, if we don’t have these baselines for wellness in place, ACES awareness and testing, and trauma-informed schools, hospitals and law enforcemet, as she is advocating for now, then we are going to pay at the end, instead of at the front of our lives. Either way we are going to pay.

JOAN WILLIAMS: It’s true, yeah.

The Center for Worklife Law Breastfeeding Policy Summit

LISA REAGAN: So, it is better to just create a healthy population from the beginning. And this takes us into the breastfeeding workplace law, the breastfeeding policy summit. This summit wasn’t necessarily about the reasons why we should advocate for breastfeeding, because that was a given, this was the very sophisticated and rarified air of how do we go back to our legislatures in our states and understand some of these very important insights that we learned about language, non-partisan language, and what I just said about watching the audience recoil if I talked about families, anything to do with families. We were given a sheet at the summit about what verbiage may or may not work and what you may want to strike from your language when you are talking with a legislator. This kind of training and thinking, I found to be truly invaluable, especially when we’re talking about practical reality of real systemic change in America. I don’t see another fast track.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Yeah, yeah. I think there is really an opportunity now to make a lot of progress on breastfeeding. One of the things that we have done at WorkLife Law from the very beginning is tried to bridge that class culture gap that I talked about before. This is also a regional gap. So, you would talk very differently in California to legislators then you would in Mississippi.

From the very beginning, we have seen the kind of advocacy we do around family caregivers as very much standing up for the values people hold in family life. In fact, the tagline of WorkLife Law at one point was, “Redesigning life around the values people hold in family life.” I think it is important, depending on the context, to be able to hum this tune in two different keys in the context of conservatism, when you’re talking about breastfeeding is are you talking about whether people can take the personal responsibility to raise the healthiest child that they can and support themselves economically and not get fired in the process?

So, we are deeply talking about personal responsibility and we are talking about the values that people hold that family life is important, that family life is central, that children are cherished, and all of that language is very, very good. That works well. That language works well in red states and to get conservative voters even in blue states. “I think that families are important. I believe in personal responsibility.” Now, these words have been used in some ugly ways, but I’m not using it in ugly ways. I am using it in ways in order to explain to Americans why they need to create less family hostile public policy.

On the other hand, in a very blue state like California, I mean, God forbid that you should talk about nursing mothers because there are trans men that may be nursing. So, it’s a totally different theme. But somebody who is working with the state legislature probably needs to be able to frame the message in at least two different ways and perhaps more.

LISA REAGAN: There were a number of takeaways from the summit, what would you like us to know? There is so much. I am keeping an eye on the time right now, so I am going to put it off on you.

JOAN WILLIAMS: One thing that’s really important in breastfeeding advocacy is to not guilt trip women who choose not to breastfeed. There are many ways to raise a healthy child and that has to be an important message. On the other hand, many women do choose to breastfeed and once you are breastfeeding, it is really important for a mother or a breastfeeding worker to have access to regular breaks in order to pump or breastfeed. If she doesn’t, she’s liable to get a very painful and possibly serious breast infection where your temperature spikes up and it can turn into a serious health condition.

It is also very important for a breastfeeding worker to have a clean place to pump, because after all, you wouldn’t want your food prepared in a bathroom. Babies don’t have as strong immune systems as yours is. Often in small employers, this makes them very anxious, and I can understand that, but there is typically a way with a little bit of forethought, that employers, even small employers, can arrange for a private place for pumping. For example, if you’re in a retail environment, there is often a small manager’s office in the back that a woman can use for a few minutes in order to pump her milk. Often breastfeeding opponents strike this as an incredible burden on employers. But really what is the incredibly burden on employers is if they lose a trained and effective employee after the other because it’s a worker who needs to breastfeed and the employer is being extremely rigid.

One of the things that we found in our report on breastfeeding discrimination is that many, many breastfeeding workers who experience discrimination end up losing their jobs. That’s terrible for women. That’s terrible for children. It is also terrible for those women’s employers. I speak as an employer. I have been an employer for over 20 years. I can’t pretend that it is not sometimes a nuisance when women have children or when women need to breastfeed. It is also a nuisance when people have a heart attack. And it would be far better if workers didn’t have bodies at all. But that’s not the workforce you’re dealing with, the workforce is of human beings and they have heart attacks and they need to breastfeed, and that means that if you pretend otherwise, you are going to be losing one conscientious trained worker after the other and you may not be counting up that expense, but it is a very steep expense. It does not make sense from a pure employer standpoint. That’s another argument that is going to be very persuasive in some state legislatures with legislators who are very concerned about putting undue burdens on businesses, especially small business.

LISA REAGAN: Well, I can tell you a bit of good news. That is in Virginia this year I created the Workplace Breastfeeding Award program for employers to rank themselves in this application process they would go through and see how they’re doing and they would come out the other side and they would get a bronze, silver, or a gold award. It is just a pilot project that was paid for with the CDC grant for the state of Virginia, but the response with no budget for advertising, was tremendous.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Wow.

LISA REAGAN: We had 23 companies sign up and received their awards. Most of them were the big companies though, NASA, Naval Weapons Station, big companies, who are able to do what you’re talking about to provide this level of space. There were some smaller businesses that were in there, but by far it was, at least this year, and honestly, I was just really thrilled that they got the awards.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Congratulations. That’s such a great idea and a great accomplishment and I really think that you get the best out of people by speaking to their best selves.

LISA REAGAN: Yes.

JOAN WILLIAMS: And not demonize them, so that kind of awards program can have a really big impact, particularly if it continues to grow. And it will provide you and I am sure you are all over this, with really concrete descriptions like, you might think it is really difficult to give suitable breastfeeding space in this type of job, but here’s an employer who is doing it and here is exactly how. I really think a lot of this is a failure of imagination. The failure of imagination goes back to very judgmental set of thoughts that stem from the ideal worker. The ideal worker doesn’t need time off for breastfeeding. Well, yes, they do. They are conscientious. They are conscientious about their job. They need to keep their job to support their child. They also want to be a good mom. Those are just the kind of workers that you want and that’s the importance of that kind of prize program that you’ve established. Congratulations.

LISA REAGAN: Well, that was the state who funded and directed that program, so we will see how that takes off over the years.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Absolutely.

LISA REAGAN: I want to thank you again for coming on and talking to us. I am so grateful that we could cover this big picture territory, which I feel like reorients the discussion and also for activists to help us see what are the real hidden challenges that perhaps we are not perceiving. What are some of our own, as you’ve illuminated for us, class conflicts, class bias, class cluelessness that we’re not perceiving and how to approach the issue of breastfeeding in the workplace. This all applies.

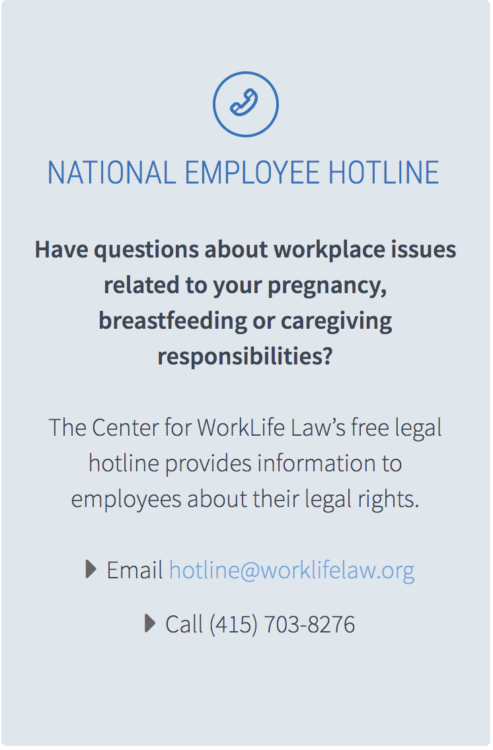

JOAN WILLIAMS: I have one final thought as I think about it. We have run a hotline for workers who have encountered discrimination. We have run it for 20 years. So, if people do encounter discrimination, they should definitely feel free to call our hotline. I can give that number in a minute. The other thing to keep in mind is that one of the things that we have found over the years is that sadly sometimes white women are offered accommodations that are denied to women of color. If you see that kind of pattern in your workplace, you know, how you want to handle it, there’s lots of different ways to handle it. But that’s race discrimination and that’s illegal. So that’s one thing that people should keep in mind as they kind of try to navigate these issues.

LISA REAGAN: Yes…

JOAN WILLIAMS: Can I give you that hotline number? The hotline number is 415-703-8276.

LISA REAGAN: You can also go to worklifelaw.org and visit the site and find a tremendous amount of resources there.

JOAN WILLIAMS: The hotline, the email is hotline@worklifelaw.org.

If you’re a worker and you’re having challenges based on breastfeeding or other caregiving responsibilities, you can check out our webpage at “Pregnant at Work” or just go to the WorkLife Law webpage. If you’re a student and you are having similar challenges, you can go to our webpage at “The Pregnant Scholar”.

LISA REAGAN: Excellent. I will make sure to have all of those resources and their links.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Wonderful.

LISA REAGAN: Alright. Well, thank you so much again for coming and I look forward to hopefully talking to you again soon.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Thank you. I hope you feel better.

LISA REAGAN: You too. Thank you. Goodbye.

JOAN WILLIAMS: Bye bye.

RESOURCES

Center for Worklife Law’s Projects:

Free National Worker and Student Legal Hotline: 415-703-8276

Pregnant@Work. This online resource center provides tools and educational materials for pregnant and breastfeeding workers, the healthcare professionals who treat them, and the attorneys who represent them. It also has useful materials for companies, human resources professionals, and management attorneys that can assist in navigating the many legal and practical considerations around pregnancy and breastfeeding accommodations.

The Pregnancy Scholar. This site provides resources for students, postdocs, faculty, administrators, and others in institutions of higher education, including colleges, community colleges, universities, and similar programs. Those interested in learning more about Title IX pregnancy protection in grade school should review the Department of Education’s Guidance on the topic.

Exposed: Discrimination Against Breastfeeding Workers. This first comprehensive report on breastfeeding discrimination reveals widespread and devastating consequences for breastfeeding workers.