Part III in Kindred’s Series

About Kindred’s Black Men, Breastfeeding and Social Justice Series: In this series, Lisa Reagan talks with the Wisdom Council members of Reaching Our Brothers Everywhere, ROBE, Calvin Williams and Kevin Sherman, who share their extraordinary stories of forging a new “generative” path to fatherhood, one that prepares black fathers to become crucial advocates and supporters “to increase breastfeeding rates and decrease infant mortality rates within African-American communities.”

The maternal morbidity, infant death and low breastfeeding rates (a path to lifelong wellness) in African-American communities are the results of institutional and structural racism, gender inequality, and living in the one developed country on Earth that does not provide social support for families, such as paid family leave, healthcare, and worklife laws for fathers.

While ROBE’s wisdom council members seek to “educate, equip and empower” new fathers, they, and the fathers they serve face the persistent cultural myth of black fathers as absent fathers. A damaging mythology contradicted by CDC data that shows:

- Most black fathers live with their children. There are about 2.5 million who live with their children, and 1.7 million who don’t, according to the CDC.

- Black dads who live with their children are actually the most involved fathers of all, on average, a CDC study found.

For more academic insights into breaking stereotypes of black fathers, see Understanding the Positive Impacts of African American Fathers, or any work by Waldo E. Johnson, Jr., who has been deeply immersed in the study of black fathers and families for over two decades.

About Kindred’s Editor: Oral history has its roots in the sharing of stories throughout the centuries. It is a primary source of historical data, gathering information from living individuals via recorded interviews. Lisa Reagan’s interviews of thought-leaders, researchers, activists, parents and professionals serves as an oral history of the organic conscious parenting/family wellness movement in the United States and globally since 1999. Follow her podcasts, and this series, on Apple Music/iTunes, SoundCloud and here on Kindred.

Kindred’s Meet the Men of ROBE Series

Part I: Meet ROBE. An introduction to Reaching Our Brothers Everywhere with founders Wesley Bugg, JD, and George Bugg, MD.

Part II: Meet ROSE: Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere, the inspiration for ROBE. ROSE’s Chief Empowerment Officer, Kimarie Bugg, DNP, shares her story of transforming her 40 year nursing career into a diversity, equity and inclusion nonprofit to train health care professionals, breastfeeding consultants and families.

Part III: The Men Of ROBE: Standing At The Intersection Of Fatherhood, Infant Mortality, Breastfeeding And Social Justice. Listen to stories of ROBE’s Wisdom Council members, Calvin Williams and Kevin Sherman, below.

Part IV:The Fatherhood Narrative: What Support Circles Reveal About Fears and Hopes. An interview with Carl Route, Jr, and Gregory Long, Wisdom Council Members of ROBE.

Part III: The Men Of ROBE: Standing At The Intersection Of Fatherhood, Infant Mortality, Breastfeeding And Social Justice

Meet Calvin Williams and Kevin Sherman

“I saw breastfeeding as a healing mechanism for distressed families. I saw it as a way for men to reacquire some of their humanity. I saw it as a way for a man to the generative part of fathering. Supporting breastfeeding is generative. Like my child is going to benefit from this for 40, 50, or 60 years. ” – Calvin Williams

Calvin Williams is a co-author of and Master Trainer for the “On My Shoulders” fatherhood curriculum, an innovative, evidence-based program that equips fathers for success in relationships with their children and co-parenting partners. He previously served as the Director of Fatherhood Services at Public Strategies Incorporated in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Before joining Public Strategies, Mr. Williams was as the Program Director for the Lighthouse Youth Services REAL Dads Program, and for the Services United for Mothers and Adolescents Fatherhood Project, both in Cincinnati, Ohio. He is a founding and current board member with the Ohio Practitioners Network for Fathers & Families, a statewide training, advocacy and support organization for fatherhood practitioners.

“When I see a billboard of an African American family,I see a mother and kids. The dad is nowhere in the picture, so if he don’t see himself in the picture, he feel like he don’t belongs there. The more he sees himself in the picture the more he feels like he belongs there. That’s doing justice.” – Kevin Sherman

Kevin Sherman was released from prison after spending 30 years incarcerated. He was born and raised in New Orleans uptown. At an early age he got into street crime, which led him to being shot then incarcerated at the age of 15. While incarcerated he began to educate himself and became a spokesperson for young men entering the prison system. Once Kevin was released, he continued his work with the youth by ensuring every young man and woman has the opportunity to avoid the pit-falls of the so-called street life. Kevin has an exceptional background as a youth and adult mentor, as well as a fatherhood and substance abuse peer facilitator. In 2015 Kevin led the Unity Project in Baton Rouge as the Youth Program Director. There he taught adult basic life skills and empowerment courses, parenting classes, mentored 250 youths and assisted them in obtaining a GED and facilitated instructional and valuable trips to Angola Prison. Kevin now facilitates the Male Fatherhood Program for Healthy Start New Orleans and NOLA for Life. He also is a Community Outreach Worker for Healthy Start.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

(Click on the title below to pop down to that section.)

- Calvin’s Story

- A Strategy for “Generative” Fatherhood: Becoming A Black, Male Certified Lactation Consultant

- Cultural Mythology and Reality: Unpacking and Unlearning Socialized Masculinity

- Kevin’s Story

- Heroic Community Healers: “Many are sitting in prison.”

- Building and Keeping Trust: The Path to Community Healing and Empowerment

- Fathers, Capitalism, and Racism: Why Is Fatherhood Not Recognized As Social Justice Work?

- Where’s The Hope for the Future?

LISA REAGAN: Welcome to Kindred. This is Lisa Reagan and today we continue Kindred’s Black Men, Breastfeeding and Social Justice Series. You can visit Kindred’s website and find more of the series’ interviews, transcripts and resources for equity, diversity and inclusion education.

Today I am joined by two Wisdom Council members from Reaching Our Brothers Everywhere, ROBE. Calvin Williams, who is joining us from Cincinnati, and Kevin Sherman, in New Orleans.

I am also joined by Kindred’s social justice editor, David Metler, and Kindred’s Research Student from the University of California in Santa Barbara, Reshma Grewal.

You are invited to join our virtual campfire as we listen to Calvin and Kevin’s stories of forging a new “generative” path to fatherhood, and how this work connects breastfeeding and birth in the African-American community to social justice reforms and education.

So welcome everyone.

Instead of reading off your bios, which are considerable, I’d really just rather hear your stories from you and how your backgrounds connect with the work that you’re doing with ROBE. Calvin, how did you get to where you are? It seems like your background in fatherhood education prepared you for this work.

Calvin’s Story

CALVIN: Yes, actually it has, and I go all the way back to my father. I come from a very poor family in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My father met and married my mother when she had five children from three other different men. None of those men were involved with my step-brothers’ and sisters’ lives. My father was 48 years old when he had me. He and my mom broke up and I was one of the only children to go with him, and I don’t remember any conflict or struggle about that. That’s what’s so interesting. I just remember when he said, “Me and your mom are no longer going to be together,” I was just like, “I’m with you.”

I saw breastfeeding as a healing mechanism for distressed families. I saw it as a way for men to reacquire some of their humanity. I saw it as a way for a man to the generative part of fathering. Supporting breastfeeding is generative. Like my child is going to benefit from this for 40, 50, or 60 years.

CALVIN WILLIAMS

He set me up for the work that I’m doing by the way that he felt about me and the way I describe it is, he transmitted some things to me. He did some things to me that endure to this day. I feel him deeply at all times, and in positive spirit form. It was the experience of what he transmitted to me, and when I had my son, the process of becoming a father when my son was born, set me up for the work that I’m doing.

I was a manager at Rowley’s in Cincinnati back in the early 1990s, and one of my cooks was involved with a little group in the Whitton Barry housing project in Cincinnati. And because I was so compassionate and kind to this guy in helping him try to advance himself in life, he said, “Man, come to our little group meetings in Whitton Barry.” Now Whitton Barry at that time was, no mincing words, a dangerous housing project. You know, crime-ridden, all the earmarks of public housing back in those days. I went to the meeting with him, and there were drug dealers, unemployed men, formerly incarcerated, people who were working, just every stripe of man, and I started attending those meetings. I just attended as a person who was in love with my people and I just wanted to be there and help. It wasn’t an organization, but the gentlemen who were backing that group, who were helping it form and stay together, decided to make a formal organization. At the time, at that point in my life my resume was like six single lines of stuff; not much on it at all because I didn’t go to college.

I put in my resume to become Executive Director of what became the Genesis Men’s program. These men own national businesses. They were just altruistic and trying to help, and so they did a national search like people of that ilk would do for an executive director of their fledgling organization. Lo’ and behold they chose me, and that was the beginning of this journey. The Genesis Men’s program in Cincinnati is my first nonprofit social service experience. I was executive director, and we had tremendous success. It was very well documented by the local news, and it was just very successful and that set me up for where I am today.

A Strategy for “Generative” Fatherhood: Becoming A Black, Male Certified Lactation Consultant

LISA: Calvin, how did you decide to become a lactation consultant? I’m not sure how many men there are right now who are lactation consultants, and how does that play into your ROBE work?

CALVIN: Well, in 2017, here in Cincinnati, I went to a breastfeeding forum at the University of Cincinnati. It was a one-day forum and I was asked to spend 15 minutes talking about the fatherhood program in Cincinnati that I was connected to. I did some contract work for this program, and they said just describe the Talbert House Fatherhood project. At that time, the Talbert House Fatherhood project was starting to use curriculum that included thoughts about breastfeeding. So, I did my little 15-minute talk. I shared the podium with someone who had 15 minutes as well. I was walking back to my seat and somebody touched my arm, and I looked down and it was a lady and she said, “You should come to Atlanta.” And I am like, okay. I was sitting behind her. You know, when you’re at conferences people give you business cards and say, “We’re gonna do this,” and you take it in good faith, but you never know.

“When I became a CLC, my heart and my mind fused fatherhood and breast-feeding in service to the people and the communities that I care about. And I just made breast-feeding a part of fatherhood in me and started carrying that forward”

CALVIN WILLIAMS

So, I sat behind her and she said, “Give me your business card.” I didn’t have any business cards, so I scribbled my stuff on the back of one of hers and I thought, for me, this is a deal breaker; this guy’s not even organized. But sure enough, that was in May and in June, I was in Atlanta with Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere at an infant mortality summit that they organized. So, that was in June. Then in August I was at their Sixth Annual Breastfeeding Conference and then in December I was in Miami with ROSE, so Kimarie Bugg, the woman who touched my arm and said, “You should come to Atlanta,” started this whole process.

At the breastfeeding conference in New Orleans I was blown away. I am in a room with 500 women – IBCLCs, doulas, CLCs, peer counselors, researchers – and I had never experienced that. For three days I’m soaking this in. I’m transformed, seriously. I wrote in the margin of my note paper, “Can a man be a CLC?” I shared that with Kimarie and about four months later, she alerted me to a CLC training happening in Cincinnati. She provided a scholarship for me and paid for all the other testing fees and everything. So, I took the course and I passed the test and lo’ and behold: CLC (Certified Lactation Consultant).

LISA: I saw a picture of you with a T-shirt on that had the football on it. (Laughs together.) You know what I am talking about then. Tell me about that T-shirt.

CALVIN: I was actually in Linda Smith’s IBCLC prep course. She is world-renowned in breastfeeding and safe sleep, and I had one of the T-shirts with me. One day I went to the course and said, “I’m going to wear this T-shirt.” The T-shirt was designed by Kevin Sherman (on this call with us). It was his idea, his creation, and his design. Kevin had the concept of the little football laces on a drop of fluid indicating breast milk, and it said, “Breastfeeding is a Team Sport.” So that’s the story behind the T-shirt.

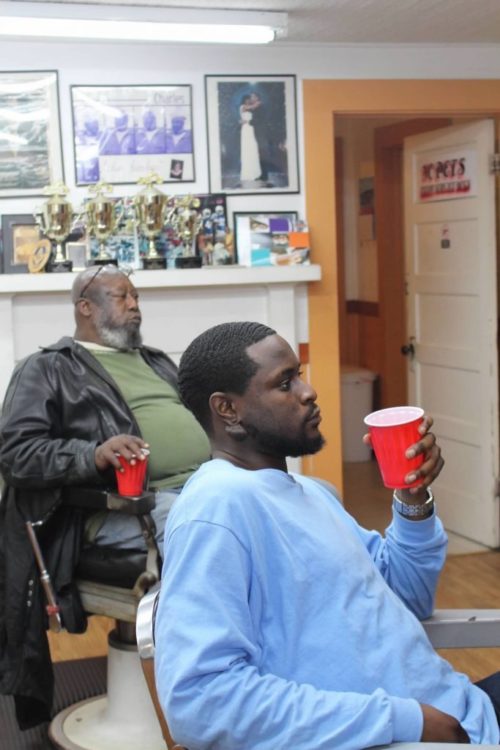

LISA: That is a great T-shirt. I love that T-shirt. How has it been, being a lactation consultant and reaching men. Are there messages that help you? I’ve seen your presentations on how you’ve come into barbershops (see photo gallery on this page), and a vegan farm in Mississippi. How does that work out?

CALVIN: Fatherhood has been my passion for almost two decades. It’s my passion. It’s my life’s work. I am just so blessed to have been in that work. So, when I became a CLC my heart and my mind fused fatherhood and breastfeeding in service to the communities and people I care about and I just made breastfeeding a part of fatherhood in me and then started carrying that forward.

Because I was a CLC and a man, people started asking me to do breastfeeding workshops for fathers, or actually, I did more fathers and breastfeeding workshops for organizations and service providers. I started developing and crafting messages – again everything starts with the heart – about breastfeeding, not only the benefits to children, the importance of it, the benefits to the mom, but I saw it as a healing mechanism for distressed families. I saw it as a way for men to reacquire some of their humanity. I saw it as a way for a man to the generative part of fathering. Supporting breastfeeding is generative. Like my child is going to benefit from this for 40, 50, or 60 years.

So, all of that started rolling around in me and I started blending the fatherhood concepts and philosophies and ideas and research and – the way my head works – I saw breastfeeding in everything. So, I just started developing content and messages and that was it.

Caption for gallery below: ROBE members meeting community members in a barbershop for breastfeeding education outreach.

LISA: Your insight is remarkable, that you put those pieces together. I am just going to convey what I saw at the national conference when you spoke, then I’m going to turn this next section over to Dave because I want him to be able to ask some questions about the social justice piece and then we’re going to go back to Kevin for his story.

When I was at the National Breastfeeding Conference and Convention in Bethesda, Maryland last year, same kind of room you’re talking about, hundreds of people, a very passionate crowd. I talked to Kimarie and Laurel Wilson, who are on the board for the USBC in the last few weeks, that conference had shifted in the last couple of years from being a predominantly white professional conference and organization to being this incredibly dynamic and diverse organization and gathering. It just knocked my socks off to be there this past year. I was so impressed with the transformative work that they’d done and the energy in the room.

For the benefit of the listener, I’ll tell the story: I had been at this conference for three days and we’re all tired, and the very last group of people to get up to speak are the ROBE guys, and I am sitting at my desk, and I am doing things and trying to pack up a little bit. It’s three o’clock on a Sunday afternoon, my back is to the stage, and I hear someone say that they “envision rivers of human milk flowing in the street to wash away systems of oppression,” and my knees kind of went out a little bit because I had never heard anyone say that before, and then when I turned around and there is a stage full of men who are delivering this message, I just had to sit down. I’m still very moved by the presentation that you all did. (see the video below.) But this understanding of breastfeeding as being this powerful and this transformative was so moving to me, this is why we’re talking now. Because I wanted to know, and for our listeners t know, who you were.

Cultural Mythology and Reality: Unpacking and Unlearning Socialized Masculinity

DAVE METLER: I’m struck by your story, Calvin. I think the piece where you mention men reacquiring their humanity through the process of really getting involved in nurturing ways in the family and breastfeeding being really, it seems like the main focus area, at least that we’ve been talking about so far. I just wonder if you could say more about that, about socialization for men and why is there so much that needs to be unlearned from men that’s just not true that comes from your question of, “Can a man be a CLC?” That’s actually at the root of why that question even needs to be asked. You know, where does the doubt, where does the fear, the being not able to have the nurturing part of masculinity oppressed or not to be able to have that part of masculinity expressed. Where have you connected in with men around that socialization and how to start to unlearn some of what men have learned through socialization?

Engaging with men and hearing – that’s talking with thousands and thousands of men through the years I’ve been doing fatherhood work – I just see potential. I have confidence in them. I love them. I see potential, and it makes it easier for me to see what we are up against in terms of this socialization.

CALVIN WILLIAMS

CALVIN: Yea, I think it’s a sad deal that men in this society get socialized the way they do and one thing I think about is there’s no one masculinity/masculinities, because there are more ways for a man to be a man than there are not. And I think I know my own process of healing and learning self-compassion and self-care and self-love is a big part of that. I learned there was more for me in my relationships and in my life changing my path to not working to be the quote/unquote traditional masculine man, but it also came about in my work with men because my whole thing from the beginning is I love the people I serve, and because I love them I am listening to and feeling them and taking them in, and I experienced the other parts of men who otherwise would be wearing the masks. Engaging with men and hearing – that’s talking with thousands and thousands of men through the years I’ve been doing fatherhood work – I just see potential. I have confidence in them. I love them. I see potential, and it makes it easier for me to see what we are up against in terms of this socialization.

So that’s pretty much how I acquired it. I am a co-author of a fatherhood curriculum called “On My Shoulders.” I was the fatherhood consultant on the curriculum development team, and they really listened to me a lot, and I said we need to have something in here about manhood and masculinity, so I wrote a unit called “Free to Be.” The whole concept was men are free to be the type of man that they want to be, and so it was a unit where I created content around unpacking and examining, not telling men what to do and who to be.

Unpacking, examining, and then looking at the diverse range of manhood that’s possible and available to people, and then also acknowledging that for some men traditional masculinity is the right fit, whatever that means. For a lot of men – really thinking about boys getting socialized into that traditional masculinity – that’s where it’s really hard to see and to stomach.

I saw breastfeeding as an opportunity for men to really tamp down or maybe get rid of some of these oppressive ways, oppressive things that women have to deal with, especially breastfeeding in public, right? We want men to be comfortable and strong next to their woman breastfeeding in public. It’s a huge statement.

CALVIN WILLIAMS

When I’m in a grocery store one day and I hear a father tell a boy, “Boy, stop crying!” and I’m in the other aisle, I can’t see them and I hear him say, “Boy, I told you stop that crying!” And I’m not alarmed or anything. I don’t know. I’m just hearing that, but a picture comes into your mind of a certain age of child. I go around the corner, the kid’s in a stroller and I’m like, okay this isn’t the way it’s supposed to be. So, we are all endowed with not only every emotion but the physical, biological mechanisms to express those emotions, whether it’s crying, shaking, laughing, hollering, yawning, whatever and so, yeah, it’s just really hard to see that with boys. So, that’s how I got into that space.

DAVE: And just one follow-up to that, is, I really wonder how liberation for men can further liberation for women? Just how they’re actually connected and, because there is historical privilege to being a man, but in the reality of the way oppression works, we’re all oppressed by oppression in some way. There’s a differential for how men experience it and have internalized oppression and how women are experiencing oppression within family roles as well, and I think some of the ideas that I saw off of the ROBE website – of men stepping up as team players. Is that how you articulate ways in which men actually are allies to women in supporting women’s liberation as they step up to their roles in how they can support breastfeeding?

CALVIN: Yes. One of the things that I am very careful about and pointed about is men supporting breastfeeding has to equal moms/women maintaining their autonomy or even strengthening their autonomy. So, I do see that as…and you’re absolutely right. If men are oppressed women are oppressed. Oppression kind of works both ways, in little circles and cycles. Men supporting women breastfeeding help women maintain their autonomy and help women actually do what’s natural and good for them, which is going to build women up. I saw breastfeeding as an opportunity for men to really tamp down or maybe get rid of some of these oppressive ways, oppressive things that women have to deal with, especially breastfeeding in public, right? We want men to be comfortable and strong next to their woman breastfeeding in public. It’s a huge statement. I definitely saw men supporting breastfeeding as a way to liberate themselves but also, as you said, to uplift women in their lives.

DAVE: Thanks for sharing.

Kevin’s Story

NOTE: Kevin’s interview begins at the 25 minute mark of the podcast recording above.

LISA: Kevin Sherman, who’s been patiently waiting in New Orleans, we would love to hear your story of how you arrived at ROBE. It seems like your background, as well, has prepared you for the work that you’re doing? How did you get here? What is your story?

KEVIN: First of all, as you know, I’m from New Orleans, Louisiana. Grew up without a mother or father. At an early age, I ventured to the crime street life, wound up going to prison at the age of 16, and spent 30 years of my life incarcerated. During my incarceration period I began to educate myself and people in my situation. I began to try to help other young men who were coming into prison who had a similar background as myself: not having a father or not really having a support system.

As I continued to do that work I continually looked at the geographical and the color of the men that were coming in that were suffering from the same problem as me. I just began to understand all these men that was incarcerated, African American men, 85% of them had kids that they had left in the street. Through the warden, I was the first inmate in Louisiana, one of the first in the state of Louisiana, that was trained to get these men an understanding on who we really failed and understand that we had failed our kids. We had failed our families, When I looked at the overall picture, the number one biggest failure was the kids because the kids were left to fend for themselves.

I began to teach this curriculum and get men to understand and give men some empowerment and a sense of importance. Once I was released from prison after 30 years, this was my calling: to help me bridge the gap with their children despite what the situation was with the mother. The kids needed their father. I began to volunteer my time doing this work, recruiting men, talking to them about issues concerning them being a mainstay in their kids’ lives. A lot of times I was being enlightened at the same time because I began to understand that it was not a fact that these men didn’t want to be fathers. The fact was, they was ashamed that they could not take care of their kids, that they wasn’t given a lot of the same opportunities that their counterparts to be able to make an honest living and take care of their kids. This work became really personal to me because I come from that situation. Still today, I don’t know my father.

So, I was invited to speak at several conferences, and one of them I attended was a ROSE conference here in New Orleans. A lot of people who had heard me speak before had bought me to Mama Bugg and Wesley Bugg’s attention. This particular conference they had a set up for fathers and for doulas, and I was invited to sit on their panel – and the panel went great. I was offered the opportunity to become part of ROBE’s Wisdom Council, and that was, to this date, one of the greatest honors for me coming from where I come from: a GED self-educated man and a bunch of brothers with PhDs, doctor’s degrees was welcoming me to become a part of something so great.

At first, I wanted to decline it because of fear, because I felt that I did not fit in, but these brothers made me feel like their degrees and everything else wasn’t more important than what I had to offer. This encouragement allowed me to make the decision to join this great team and do this great work, and when I think that what’s so great with this team, because as Calvin spoke, everybody is great in different areas, but when we all come together we all can get on each other’s level on what we are dealing with.

I think before you can get African American men to come in and understand and be supportive of breastfeeding, infant mortality, and postpartum and all this you’ve got to first get them to understand how to be a father, how to be a dad, how to be that partner that’s going to be there, because if he’s not willing to do none of that, then getting them to understand other things is going to be very hard.

I think before you can get African American men to come in and understand and be supportive of breastfeeding, infant mortality, and postpartum and all this you’ve got to first get them to understand how to be a father, how to be a dad, how to be that partner that’s going to be there, because if he’s not willing to do none of that, then getting them to understand other things is going to be very hard.

KEVIN SHERMAN, ROBE WISDOM COUNCIL

I take the role of really trying to get those father’s attention so that my brothers on the Wisdom Council can educate them to what the strengths are or the chance of this child having both parents, plus a supportive father that supports breastfeeding and understands the infant mortality rate as it is on African Americans, black women being stressed out and so forth. All this connection it gives me a sense of power, and I’m telling you, when I’m with these guys I feel like one of the Marvel cartoon characters. They really energize me because I understand from a disadvantage point… I understand from the community that I come from that the resources that we use to talk about, they are available but they are not going to the community.

When a group of brothers talk about taking this to the community, not worrying about the community coming to us, now you’ve got me on board, because my thing is that a lot of the men in the community are not going to come to hear what you have to say, you have to go to them and bring your message. With all these things coming together, it really gives me a great feeling. Here in New Orleans, I have my group of men that I meet with, they’re very interested about wanting to know about breastfeeding now. They want to know about infant mortality rates. They want to know about postpartum. Things that really, people just assume that African American men don’t care about. These are one of the biggest impacts of this work since I’ve been doing it and what made me understand that this work is needed.

I had a young man, 21 years-old, that was in my fatherhood program that was excited beyond measures that he was about to become a father for the first time. What I usually do when these guys are about to become fathers, I give them a sack with deodorant, toothpaste, everything they need for an overnight stay up in the hospital. So he’s got his sack, and he is sitting in the waiting room. He’s been in the waiting room for over 2 ½ hours. The young lady who is delivering their child, she is in the back. This young lady’s mother, sister, and aunty walk through the door. The nurse walked them straight back to the young lady, and this young African American man has been sitting in the waiting room for over two and a half hours because he had twisters on his head.

Unbeknown to the nurse, who proceeded to do this unjust thing, this young man was a highly respected student and basketball player. But he was being stereotyped that he didn’t care, that his fiancée was in the back delivering his first child for the very first time. He was so excited, but when he called me, he was broken. He said, “Mr. Kevin I don’t want nothing to do with this. I’m done with it. The people don’t even much acknowledge me.” And he’s crying. At that point I stopped what I am doing, go to the hospital and let him know that the nurse is only doing what she been told that’s been going on for so long. I told him, you can be the one that can stop this right now and make a difference. You can be the reason hospitals in New Orleans change the procedures, and people understand that the most important person in the waiting room was you, not the grandmother, not the aunty, not the sister, you!

These are things that’s inspired me to do the work I do because I come from this same community. So, how I became an advocate for these young men and this is the work that I have dedicated my life to because God have gave me another opportunity. I don’t take it lightly.

Heroic Community Healers: “Many are sitting in prison.”

LISA: Kevin, when we were at the National Breastfeeding Conference last year you also spoke on stage and you said something that I thought was profound because I don’t think a lot of us as activists, especially white activists in the past, have thought this way. You said you thought the healers for your community were probably sitting in prison. What did you mean by that?

I tried to show society that there are good men that come from behind the walls, but what helps me and keeps me focused, and what I try to tell everybody that comes from that situation, I am fortunate enough that I can pick up the phone and call a Calvin, I can call a Wesley, I can call a Greg, I can call our doctors. I got a whole group of brothers that I can call whenever things are not going well.

KEVIN SHERMAN

KEVIN: Because a lot of times a lot of these men go to prison and they discover themselves and they discover who they really are. The ones that have that opportunity to come back in the community, especially when we are talking about disadvantaged communities, they are heroes to a lot of these fathers because of who they was before they went to prison. Like for instance, if they were about to have a program or something in my community, whoever gives that event, guess who they are going to come to when they want the young men there? They’re going to come to me because I can go into a community and get these young men to understand. “Hey, let’s go hear what they got to see. It may be something that would be beneficial.”

And what happens, a lot of men that are in prison are men that didn’t have fathers themselves. They don’t know what it’s like to have a father. So, when I say heroes, I’m talking about in the sense of guys who want to be so-called “street guys.” These are the guys they look up to so these are the guys that can touch their lives in a positive way if these guys have gone to prison and rehabilitated themselves. I’m not talking about men, Lisa, that go to prison and come back out with the same mentality they went in with. I’m talking about men who have really understood and accepted their mistakes and use that to come out to make other young men better.

Many times, men that go into the prison system, a lot of them come out bitter because they feel like the world owes them something. Those are not the men I’m talking about. I’m talking about the men that go into prison and say, “Hey nobody put me in this situation but myself. Let me pull on my boots, do what I can do to educate myself.” Because, understand this, the education I got in prison, it cost citizens thousands and thousands of dollars to acquire; while I’m in prison I get it free if I want it. So, I took advantage of every program that I could get into. I am a DTM in Toastmasters, InsideOut Dad. I was taken to Washington D.C. to be trained from the state of Louisiana.

I tried to show society that there are good men that come from behind the walls, but what helps me and keeps me focused, and what I try to tell everybody that comes from that situation, I am fortunate enough that I can pick up the phone and call a Calvin, I can call a Wesley, I can call a Greg, I can call our doctors. I got a whole group of brothers that I can call whenever things are not going well.

When we are talking about fathers, I have a group of guys now who have no problem with their fiancé whipping her breast out right there with them and feeding the baby because, through these brothers, I’m able to explain to these men the benefits of breastfeeding. I’m able to do that. I’m able now to sit in WIC clinics every week, go from WIC clinic to WIC clinic around the whole city of New Orleans, and sit in there and engage with dads that come through the door, not trying to take anything from WIC, but get him to understand that the baby needs breastmilk. God designed that milk to come out of that breast for a reason and getting men to understand the significance of that, just what ROBE has empowered me to do.

Before ROBE and getting with these brothers and understanding – I’m going to be honest – I found it very disgusting to see a woman whip her breast out in public because I didn’t understand. I was ignorant. It is a shame to say, but a lot of hospitals are not educating African American women on the benefits of breastfeeding when they’re going to the hospital. Just like now we’re putting a video together because I understood it and I brought it to the Wisdom Council that we needed to make this as a group of brothers that are empowering and equipping men. The hospitals don’t do it. We need to make up a toolkit, make videos explaining postpartum, because many men come from the community I come from, and you ask them what postpartum is they are going to look at you crazy.

So, here’s a woman bleeding out and this guy don’t know what to do because the hospital did not explain to this man who’s bringing the woman home who just had a baby what to look for, signs that he should recognize, that he should bring her back to the hospital or call for help. They just sent her home taking for granted these men know when they don’t, and many women have lost their lives because these men are not educated on postpartum. The Wisdom Council is putting together toolkits and videos hoping that people will put them in the waiting areas in hospitals and clinics so men can see and understand the signs and recognize them so that the woman can have a chance – that young lady can have a chance of living. We have to get past the thinking of not caring whether or not this group of men should know, when they don’t.

LISA: You are able to reach men through wining their trust. When I talked to Kimarie Bugg of ROSE, she said they’re tackling the end of training like that nurse in the hospital you were talking about was oblivious how important it was to find out who this young man is sitting there. Does he have someone that he needs to be back there supporting and being a part of this birth? Clearly, the work is tremendous that needs to be done. I just want to point out that you have the ROSE group, the Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere, and ROBE and this statement that you said from the stage about the healers for the community are probably in prison are the ones that come out understanding and having insight into a community that probably can’t come from anywhere else, can’t engineer the trust that is going to be needed to connect with them.

And I think I’m just going to stop here before I go on any further, because now I’m wandering into Dave’s territory, so I’m going to let Dave Metler, Kindred’s Social Justice Editor, take over.

Thank you so much, Kevin.

Building and Keeping Trust: The Path to Community Healing and Empowerment

DAVE: I appreciated the firepower of your story and I feel even over Zoom I just feel a lot from everything you’ve shared. I feel the challenge of working across levels of change, I mean that just comes up for me as there’s institutional changes that need to happen that you identified, and then there’s also… there’s a personal responsibility.

I remember from the ROBE videos that I watched before this talk, about one of the greatest needs in advocating for breastfeeding is confidence in breastfeeding and men as team members in supporting the confidence for women to breastfeed. It seems like confidence comes up again and again, this conviction, this confidence within the personal domain for men, the family domain. Where does that come from? How do you teach that? How do you inspire that? It seems like you’re doing that. That’s the work that you’re called to do. How does that go with the men that you’re working with? How does that confidence build? Because it seems like that’s how change is happening. It is happening within individual hearts and it’s also trying to advocate for these institutional and societal changes as well.

KEVIN: What happens is that you have a community of people that have been lied to all their life, Dave. First, going in you have to do some control damage but the thing is they are willing to give you a chance. If one or two give you a chance they’re going to let the other ones know, “Hey give him a chance.” Once you get that chance, Dave, you’ve got to build on it because if you lose it, you’ll never get it back. This is why I refuse to pass out any flyers. I refuse to deliver any speech, that whoever is giving the event, they are giving me a flyer. If this ain’t what you’re going to present and give to the people, then I’m not passing it out. Because the thing about it, when they come they’re not going to be looking at Dave, they are going to be looking at me because they may never see Dave, but I’m the one that got them there based upon the flyer that you gave me, so I’m very cautious on who sends me into a community and what are the sending me for.

What happens is that you have a community of people that have been lied to all their life, Dave. First, going in you have to do some control damage but the thing is they are willing to give you a chance. If one or two give you a chance they’re going to let the other ones know, “Hey give him a chance.” Once you get that chance, Dave, you’ve got to build on it because if you lose it, you’ll never get it back.

KEVIN SHERMAN

Once you get that trust, you’ve got to hold on to it, Dave, because we’re talking about communities that have been lied to just to get signatures on a piece of paper. People coming into them and selling them promises, so they open up to you and here you do the same thing. Now it makes it hard for anybody that’s coming behind you.

DAVE: Yeah, I hear you. The work that you all are doing with ROBE and with ROSE as well, it feels so based on trust and based on relationship and on trying to rebuild trust where trust has been broken before, which is quite a challenge.

KEVIN: The work that we’re trying to do is very hard because it is new to African American men because, for so long, they didn’t think that was a good thing to do. And not knowing that this is something that our ancestors did all their lives – they was midwives, they believe in the natural – so re-educating these young men and trying to get them to reconstruct their thinking and being even though they and the mother have differences. You also know support for her is still needed because you need to understand people wonder, “Okay, she’s only two months pregnant, where’s the dad?” He’s gone already.

So, my job in my community when I’m doing outreach and I’m talking to a young lady that’s pregnant the first time, I’m asking, “Where’s the father?” She tells me, “He don’t want to be here.” I say, “Well give me his number. Give me his number.” Right? Let me reach out to him. So, when she gives me the number, I call him. I asked him, could I meet with him and share my story of coming up without a father that led me to prison for 30 years because I left it up to other men to be my father and then they used me and led me straight to hell?

I asked these men, your kid has to be you “why”. When your kid become your “why,” nothing else gets in the way, regardless of what is the difference you and the mom ain’t work. That’s not the responsibility of the child. So, they have to understand that. When you don’t have people educating these men on this, when you’ve got men saying “F” their kids because they don’t understand why the baby mama put them on child support because she got three more kids with somebody else in order for her to get support for the other three she got to put him on child support too, when he takes care of his kid. So, we have a system that created friction too.

So, what ROBE does, when we meet, we try to find out where the reach officers are at. Here in New Orleans, I bring the child support director in. I need you to explain to these men why they’re being put on child support when they’re taking care of their kids, not just the mother of the child, for whatever reason.

These are the things that when we talk about social justice you’ve got to tell me where the justice in this is at first. I have to see the justice in this. Where the family is at, when a lot of organizations they are dealing with mothers not even inquiring much about the daddy. But you said you were about family. A family consists of a mother, child, and father. This is what I am beginning to understand here in the city of New Orleans. When I see a billboard, (which they are changing now, because they took ones down because I took it to the mayor’s attention), when I see a billboard of a European family, I see a family, a daddy, a momma, and the kids.

When I see a billboard of an African American family, I see a mother and kids. The dad is nowhere in the picture, so if he don’t see himself in the picture, he feel like he don’t belongs there. The more he sees himself in the picture the more he feels like he belongs there. That’s doing justice.

Fathers, Capitalism, and Racism: Why Is Fatherhood Not Recognized As Social Justice Work?

KEVIN: My take to any young many or any man I reach is what I give to you please give to somebody else. If I help you, help somebody else. That is my motto. That’s why when I have a father group, I have 25 to 30 guys in my group because I started out with two people, two men, and I incentivized each one of the men that they did not have no church, but the next time they came through the door they both better come with two people, two men. Peoople have a problem and say you shouldn’t have to incentivize people when you’ve got men dedicating an hour of their time to you and don’t even have a job or even know how their bills will be paid but then they come and sit in your class for an hour. You can incentivize them to let them know, “Hey, I appreciate you.” With a lot of organizations doing the same with all these men, you don’t exist. So, why not incentivize them to bring more men that you can reach. And I tell them, like I tell anybody you can come now and hold a class and say, “Kevin, I need 30 men,” and I’m going to bring you 30 men, but it’s on you whether or not you’re going to keep their attention. Whether you’re talking their language or whether you’re getting them to believe in what you’re saying. Can you sell your story to them?

That’s what’s going to give you opportunity to build. That’s what builds, especially when we’re talking about communities have been lied to and broken communities and statistics say that 80% of this neighborhood doesn’t have father’s in their homes. So, in my heart it’s about if you get two, you teach those two what you know and get them to believe in what you’re doing and the work you’re doing and they’re going to become soldiers for you. But if you break the trust of those two men you getting to do anything in the community is going to be very hard because they’re going to tell everybody you’re a fake and a fraud, you’re just like the rest of the people that came through. Does that make sense? Does that answer your question? Or are you needing more clarification?

RESHMA: No, that was great. Calvin, do you have anything to add to that?

CALVIN: I think Kevin hit it on the head. I think about the underpinnings of the fatherhood field. I was there in the beginning, the late 1980s/early 1990s, and I have just started saying this publicly because I’m tired.

The underpinnings of the fatherhood field are about moralizing and racist jokes about responsibility. The early fatherhood demonstration projects set out to answer one question, how can we get these poor irresponsible black and brown men to pay child support. That’s what the multicity demonstration projects were all about back in the 1990s, and then in the literature, it’s so funny to me, in the literature as you track the literature forward, it says, “ Oh, and then we found out they care about their kids.”

What Kevin is talking about also exists in the underpinnings of the fatherhood field, and I have been asking the question of myself and I’m starting to do it a little more out loud now is: why is fatherhood work so separate from social justice work.? I don’t understand that.

I am a whiteboard guy, I think, live, create on a whiteboard. One day, this was coming out of me and I’m not in control of this, I wrote “Fathers, Capitalism, and Racism” and I drew lines connecting all three and I just sat there and stared at it and I said, “You know what, something’s happening here and I got to figure this out in a way that I can articulate it.”

Where’s The Hope for the Future?

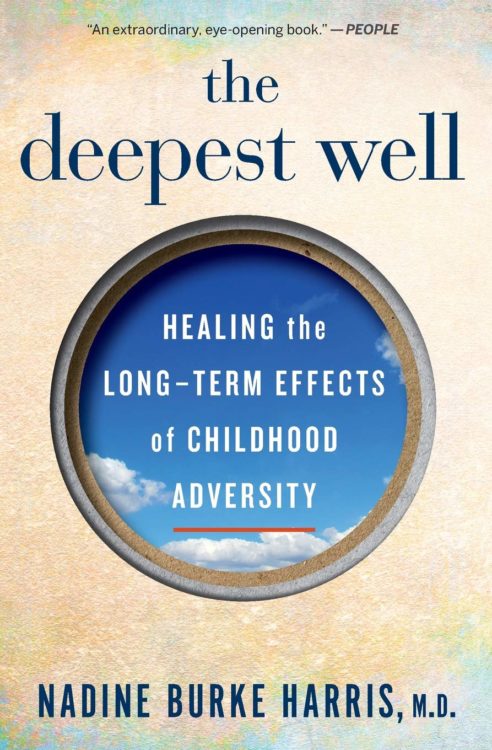

LISA: So it sounds like we’re going in the direction about transgenerational trauma a bit and how our capitalistic culture and our white supremacy culture in America is compounding and driving a lot of this. I heard someone from stage, and I hate to keep referring to the conference, but you guys did so great on that stage. I heard someone talking about being in a hospital with a mother while she was giving birth and she began to have problems with birth, and the speaker was talking about putting the community around her, putting their hands on her and recognizing that what was happening was transgenerational trauma that she was experiencing.

The recognition now of transgenerational trauma, adverse childhood events is beginning to take off. We have Nadine Burke Harris who wrote the book The Deepest Well about Adverse Childhood Events who’s now the Surgeon General for California. She is trying to bring this issue forward, but I think it’s worth mentioning that when she tried to present to professionals at conferences about this issue, and she writes about this in her book, she says she was tuned out, people weren’t listening, and when she would go down to her table to put away her materials it was the people who were cleaning up, the people that were the workers there that were part of putting on the conference who came over to her and said, “I really appreciate what you were saying. That was really incredible. That really spoke to me.” I work with a field of people including activists in Paris and professionals and researchers and I hear this all the time, that there’s a resistance to listening to stories, even though we’re solid on the science now, about this transgenerational trauma piece but the people that are receptive and understand it are the people that are affected by it in the communities. They see it right away and are going, “Oh yeah, yeah wait I know what that is.”

CALVIN: Ta-Nehisi Coates writes and talks about this. He talks about how it is the responsibility from the president on down, governors, senators all the way down through the hierarchy of the political and government chain, it is the responsibility of those people to maintain the racial status quo. It is their responsibility to hold on to and advance the story of racial degradation for people, including President Obama. He couldn’t get past that. So, what’s happening is nobody from a political standpoint has the strength and the courage to break past that.

I got his words right now, I got his exact words: “They are the caretakers of our racist history.” And that struck me because even President Obama, he couldn’t cross that line. He couldn’t say, “This is horrible for black people.” He has to hold that history intact. What’s the gentleman from Harvard, he’s trying to get in his own door and a cop arrests him and all. Who was that?

LISA: Oh yeah

CALVIN: You know who I’m talking about. Henry Lewis Gates, so President Obama’s response is let’s bring the cop and Henry Lewis Gates to the White House and have a beer. President Obama… listen I know people get all upset when you say anything about President Obama that’s not 1000%. He could not say, “This is dead wrong.”

We need to be moving towards an anti-racist society. That’s our only hope. Not integration, not recompense, we need to be working towards an anti-racist society for this nation to really, really grow, but we can’t do it because everybody has to hold that racist history and keep it in tact, and that’s the same thing in areas we work in with fathers and breastfeeding. That’s why the funding for fatherhood, the funding is less so in maternal child health, but in the fatherhood field the funding does not allow you to even address the underlying conditions, the disparities, the misrepresentation that puts fathers in these positions in the first place. The fatherhood field says: make them responsible.

I saw they’re already responsible. Get out of the way. Stop disinvesting in communities. Make sure jobs are available for people in their own communities. Make the culture and environment function in a way that their natural abilities to be responsible and caring and nurturing, that it comes out. That’s a huge challenge. As a society we just won’t let go of that racist past and try to envision a new day when we live in an anti-racist society. And fatherhood research around the world backs this up. Michael Lamb, David Shwalb have written a book Fathering the Cultural Context. All around the world as economics go, so goes fathering.

LISA: I hear you. I wonder… this is a discussion that we’ve been having for a long time at Kindred on different levels which is, how to shift the dominator society away from its suicidal impulses and taking a whole species off the cliff, and what people like Riane Eisler, have written about it is a perception of what is power. When I listened to the two of you present what you’re doing I see, as you said Kevin, you guys are Marvel superheroes. This is powerful, truly deeply powerful change that you’re doing on the ground.

Why is it not recognized as that? Well, because the people that believe that they have certain kinds of power now are not wanting to let go of that power. Unfortunately, a lot of that power is monetary and what could be done if we were to redistribute wealth and resources, especially in this country is tremendous but it does to me, and I’m sorry to get under my little soapbox here, seem to be such a deep shift in the hearts of people. I don’t see it happening on the scale we need it to. It just seems like we need more of you. We need more men to be trained in what you’re doing. We need this to be scalable and modeled everywhere.

I’ve definitely drifted over into David’s territory. David, what would you like to say in this piece.

DAVE: My thoughts from hearing what you’re sharing, Calvin, is I think partially just feeling like there is a huge reckoning that America has with its own history, just even being honest to a name and also deal with I think some of the darkness the story of America. I feel like Obama and Trump’s presidencies have given different challenges. I think of Obama’s as being really inspiring: We are the leaders we have been waiting for. In some ways it is a lack of waiting for the higher-ups to change everything, because you almost see Democrat/Republican, there’s so many overlaps and when you take power you take power over a country that has incredible and dark history: it has its foundation in white supremacy.

It’s an acknowledgement and understanding of the story but also a feeling of… and that story needs to change. That can be empowering with actually feeling like the work that individuals are doing is going to be disruptive of that story. Like yourself and like Kevin and the work that we’re trying to do with Kindred, and it also takes institution and societal change as well so we know that the power structures have to change; it can’t just be change on the ground and every individual is doing this change for themselves. It is also within the power of community of collective action.

I just think right now with the current crisis with Coronavirus I wonder if out of crisis there is some opportunity. I wonder if there is opportunity; I’m just thinking particularly here in Detroit for example we have some of the greatest racial disparities in the way in which Corona Virus is impacting Detroiters. But also, there’s been some crazy things happening that I think social justice activists have been fighting for a long time: to end water shutoffs, to end foreclosures on homes, to really acknowledge and affirm how many people are struggling even to pay the bills on a week in which employment levels have not reached greater than 25% of the state’s population. And I wonder if there… I hear you, I wonder if there is a need to sit with that and feel the reality of what you’ve named. And then also I wonder where’s the opportunity, where’s the hope and where do each of us put our efforts to change that.

CALVIN: Kevin, what do you have on that.

KEVIN: Dave, I’m glad that Lisa spoke of what she spoke of and I’m glad you just spoke of what you spoke of. We can continue to talk about the past because it gives us some idea of how we get to where we’re at, right? But we have to start holding all these groups and all these conferences we be going to and hearing these people talk about change.

We have to start holding everybody at these conferences and who is coming into contact with each other accountable. Because we all come together, we can be the change that’s needed. We can be that change. But what happens is, the influences that’s at the conferences we hold great conversations, we share great ideas, but once we go our separate ways we don’t try to bridge the gap and come together putting together a community, world-wide network of all these people who’s concerned about these problems coming together from different parts of the world coming together and meeting saying, “Here’s what we need to do.”

We understand what has been done. If we keep dwelling on that ain’t nothing going to get done. We understand what has been done. How can we as a community national network team, how can we change things. How can we come together and write policies that would make a difference?

We have people like you and Lisa who can broadcast these community networks to bring more people from around the world involved. See, we can’t wait on other people and this is what I always tell my guys. We can talk about what’s not being done, but what are we doing? We are attending a lot of conferences, we are giving great speeches, but we when we go our separate ways we’re not connecting. We’re not sharing ideas from New Orleans to Washington D.C. until we see each other at another conference.

Do you know how many fathers we done lost, how many babies we done lost, how many mothers we done lost between one conference this year and we’re going to go to the next conference in the next year. Do you know what difference that year would have made had we been connecting and networking as concerned people?

This is why I get tired of meetings. That’s why I refuse to attend a lot of meetings, I refuse to attend a lot of things because it’s nothing but yap, yap, yap, yap. Everybody wants to sound good and look good but when it’s all over, nobody’s connecting to do this work. We can make a change. We can change a lot of things that people keep saying can’t be changed.

I believe anything that is existing today, the group of people we have that exist today that didn’t exist back then, we have the power to change things. We have lawyers, we have doctors, we have people from all walks of life that’s a part of what we do, so you can’t tell me we can’t change things. If we all come together from an international standpoint and hold conferences and writing and presenting ideas on how we can change things. A lot of people don’t want to do things because everyone wants to be the frontrunner, so that creates a diversion among people trying to do things. I’m about just get the work done, whatever role that I play I’m cool with it. I just want to see a change where families can unite, babies can have better outcomes with both parents.

We see a lot of African American men in prison, in the graveyard. When you make a man feel important, you give him responsibility, he be living a different life. You’ve got to give him a “Why”. Each and every one of us have a “Why” in our life, why we get up and do what we do every day. We have a “Why”. Even when you don’t want to do it yourself, you think about that one person or that reason you got to go do what you got to do. You think about that why and you have to do what you have to do.

We have to think about why we do this work. Why do we do this work. You’ve got to be honest when you answer that why. A lot of people are not honest when they answer why they do this work. A lot of people are not honest. That’s where the change comes from. That’s because if we’re waiting on politicians to just up and change what we’re trying to do, we will be in our graves and gone before it happens. We have to create the foundation and pray to God that we done made enough of lead way, that we have educated enough people to continue this work the way that it’s supposed to be done. Where every young man and young woman and kid can go in the hospital and get the same treatment. It’s plain and simple.

I understand the difference and I have a whole different world perspective, and I’ve seen the difference in hospitals and a lot of the caretaking dealing with the Covid-19. I was in a hospital. I’m private insured. But I have seen people who come in who wasn’t get the sheet put over their head. Because my doctor was private-insured he’s my doctor; he’s making sure I have everything I need but the man down in the next room from me, he’s not So he’s not going to get as much attention as I’m getting. He’s not going to get the best equipment that he need in the hospital that I’m getting, because the doctor know if he write this $5000/$6000 bill to me he going to get paid because I’m private insured. So, yes, he’s going to give me the best he got.

It still exists. We can continue to continue to talk about who can change it, but we have a group of people, we have enough organizations that claim they care about these issues that we have enough of power to create a national network that can come together, write policies, and change these situations and we wouldn’t be still talking about them. Lives would be touched and changed. That’s what I wish. That’s what I wish for, that’s what I pray for.

LISA: Calvin, do you have a follow up?

CALVIN: Yeah, Dave you ask where the hope is. I see plenty of hope.

I see plenty of hope. I see hope around the Wisdom Council, and I see that hope get ignited when we go into a city. When they see a Kevin and a me and a Wesley and Greg Long and Clifton King, when they see us interacting authentic, natural, and full of vibrancy based on love and compassion, I see how we touch people. I see hundreds and hundreds of people who are working towards these things we are talking about. They don’t make the news. They don’t make the newspaper. You can read about them in Color Lines, which is one of my favorite (laughs). You can read about them in a lot of publications, so I have a tremendous amount of hope. I love the young activist class that I am perceiving and reading about around the country, and I think, similar to the Bacons Rebellion in Virginia, sooner or later there’s going to be this multiracial, multicultural throng who says no, no more, it’s over. That’s what I believe. That’s the hope that I run with every day.

LISA: I believe that too, Calvin, I do. Do you have follow-ups Dave or Reshma or Calvin or Kevin?

DAVE: I think, Calvin, when you talked about putting fatherhood, capitalism, racism on the board and trying to draw the lines between them, I’ve heard that when you want to understand something you try to change it, that’s how you can really learn how something works, how it is the way it is. And I think that the hardest things to change, like capitalism, fatherhood, racism and the interconnections between them I think that there’s some wisdom that ROBE is bringing to the significance of the changes that ROBE and ROSE are working towards… the significance of those change because each of you brings your story, your authenticity, and your network together the collective power with young people. As people come together around these types of changes that you have hope to make, I think that’s where the power is, and that’s what gives me hope too. So, I appreciate that you shared that and that we can have this conversation.

KEVIN: Dave, and that’s what great about it. What’s great about ROBE is what I told you from the beginning. I don’t know whether, how they went about collecting…we all had our meeting in Florida where we all came together, right? But when they made this Wisdom Council, we got people picked from all walks of life and you’ve got educated men, you have doctors, you have lawyers, you have practitioners. We have Dr. George Bugg, who is one of the top doctors in Georgia in his field, right? We have this great group of men who can speak on any aspect that you want to talk about when we are speaking to the mass of stuff that’s taking place in the African American communities that we need to make a change in.

One thing I’m grateful for, that now we have a friendship with you all that we can have a discussion now. Because what happens is that a lot of people don’t want to hear the truth, Dave. A lot of people don’t want to hear the truth. That’s why I tell people all the time, be mindful when you invite me to your conference. You’re going to get me. You’re not about to get nothing phony. You’re not going to never see me walk to the podium with a piece of paper and read to you, because it’s coming from here. I’m giving the people what they want to hear. I’m not giving you something that I have to make up. I want to give you me. I want to give you all of me so you can understand that and there be no misconception.

So, I’m grateful that Lisa had the opportunity to be in the audience when we were speaking and we captured her attention and this great friendship has developed, and now it gives ROBE a chance for people to hear this story and understand that we just a group of men that try to do this work and make a difference. We’re trying to truly make a difference and help. People who are really trying to do this work, they will be more willing to work with ROBE, because we have a lot to offer and a lot to bring to the table and the best thing about it is it’s genuine. And it’s boots on the ground.

When I go to Ohio I’m not going to go sit, and all be like Calvin let’s go here, let’s go there, I’m boots on the ground. The same thing when we come here. It’s boots on the ground. I want you to see how fathers are living, how fathers are being treated, what they have for fathers. I want you to understand because maybe you can help me to help these brothers. So, this is what it’s about. So, Dave, you know, being a part of the Wisdom Council we are grateful for the opportunities and we are blessed that you all took the time to want to do this with us so people can get to understand and learn more about ROBE, because the world is going to know about ROBE. The whole world will know, sooner than later, that we’re a group of brothers that are going to try to reach every brother around this world that we can.

CALVIN: You know what, I have to add that, and this is from our amazing executive director, G. Wesley Bugg. Wesley said one day, and it stuck with me, he said, “You don’t have to be black, you don’t even have to be a man to be a brother. If you care about black infants dying, if you care about black maternal morbidity and mortality, you can be a brother.”

KEVIN: That’s a fact.

LISA: Well, can you tell us where to go? Let’s have our readers, leave them with some resources. Where can they find you online and where would you like for them to go to find the resources and to contact you?

CALVIN: For me, it’s…you know, I have a website lucianfamilies.com. You can check me out there. Obviously, I have a Facebook page. Also, my work with Hamilton County, Ohio, you can check that out at hcfathers.org, where we have a county wide fatherhood collaborative. Yeah, those are the places you can get at me.

LISA: Okay, and the ROBE website is breastfeedingROBE.org.

CALVIN: BreastfeedingROBE.org, that’s correct. And I’ll say this to what Kevin said about the Wisdom Council. I have a saying on the home page of my website and it’s from a Native American author and I borrowed it, and it says the true test of kinship is not blood, it’s behavior. And so, this Wisdom Council behaves like a band of brothers. So that’s what makes us special.

LISA: It is a special group. I told you that at that conference and seeing you all together and speak; I don’t know how often you do that or where the next one’s going to be since we’re all kind of in a quarantine mode, maybe you all could do Zoom conferences. But, you’re collaboration and your dynamics together was really moving. It was the best part of the conference, it really was. I say that without hesitation and not the least bit… that’s not an overstatement at all. It was just really moving, and as you said, Kevin, it was very clear that you were bringing your heart and I do think that really inspires a lot of hope in people to see that… we haven’t all be ground down, we’re all exhausted. I’m still here after 22 years of activism people, so you can show up to. You can do this.

CALVIN: Can I say something to you guys? Thank you for being allies. Thank you.

LISA: Thank you, Calvin. I can’t tell your story for you. I can only make a place at the table like Kevin said. A place at the table is always here at Kindred, and I’m just thrilled that I was able to discover you there and I can’t wait to see what else you all have. The resources that you’re coming out with are so helpful. Some of them like the video is so very simple but it really illustrates for me this very practical way of working together again as a team and that’s what it’s going to take, and for us to think that we’re going to go off in isolation we’re going to figure this out and it’s an intellectual process ourselves, and then as you say, Kevin, get together at a conference and present our intellectual findings. That day is done. It was what I feel was a white intellectual agenda that had its chance and we already know the science. We already know the purpose and necessity of breastfeeding in communities. It is a social justice issue and that is not the tactic that is going to get us where we are going. So, I appreciate, as you said, the boots on the ground, that’s it.

Kevin, do you want people to reach you at the ROBE website?

KEVIN: Oh yeah, kevinsherman@breastfeedingROBE.com and my other email is kdsherman@nola.gov . As you know I am the fatherhood coordinator for the Healthy Start in New Orleans here. I’m the fatherhood coordinator of the Crescent City Dad’s. I coordinate the Crescent City Dad’s classes here in New Orleans. I am also the mentor for a Catholic charity youth program, and I also have my own youth organization where I take young kids for a life changing experience, not a scare straight, but an all-day experience, to the Louisiana State prison so guys can share their stories with them in hopes that these young people get it and make a life changing decision.

LISA: That sounds like the opposite of scared straight.

KEVIN: Yeah, scared straight is not good. A lot of bad things have come out of scared straight programs because kids have to reestablish who they really are after you done took them in a prison and pumped them out when people were scared. Now they will wind up hurting somebody, because now kids are people that are seen and not who they profess to be, so now they’ve got to prove I am that person and why I am hurting people. So, I believe that just bringing kids in, letting guys that truly transformed in prison, and I’m talking about people who are mamas, doctors, lawyers, prominent people who have made mistakes in their lives and share their stories with these young kids and hope that these kids would just take these stories and make a difference. A lot of kids have.

It’s just that people have to understand that, and I teach all my young kids this; nobody should want more for you than you want for yourself, and that’s just what I live by. And I tell them if somebody wants something from you, you’ve got to go harder than them. Don’t let them want more for you than you want for yourself. That gives them that push. I will leave with this, and I’m talking about in any kind of work we do, especially the work that we’re doing now, and I always express this to my Wisdom Council brothers. I teach this to a lot of people who want to embark on fatherhood, dinner with youths or anything. Lisa, you can’t help me if you don’t know me.

LISA: Right.

KEVIN: You can’t just take for instance that because I live next door to Joey, that my life is the same as Joey. So, you can treat me and Joey the same. No, you have to get to know me to help me. You can’t tell me you want to help, me because my first question to you is how you going to help me, you don’t know my story. You’ve got to hear my story and then you can see how you can help me, how do you fit into my story. Because you may not fit in, but after hearing my story you may know the person that can. I can’t help you with that, but Dave can. That’s when you get to know a person.

LISA: Try to envision what our culture would look like if we decided that a real super power would be that of listening.

Well, thank you so much. Don’t hang up yet everybody. I’m going to stop our recording. I am going to tell our listeners that they can find the transcript for this call at kindredmedia.org. You can also look for podcast to share on iTunes, Amazon Cloud, YouTube and again kindredmedia.org. This is an ongoing series for right now. I don’t know when we are going to stop at this point. We have a lot to talk about. We have a couple more ROBE members coming forward to talk to us about their work and I look forward to sharing these stories with you.