If Scotland Can Do It, Can America?

An Interview with Suzanne Zeedyk, PhD

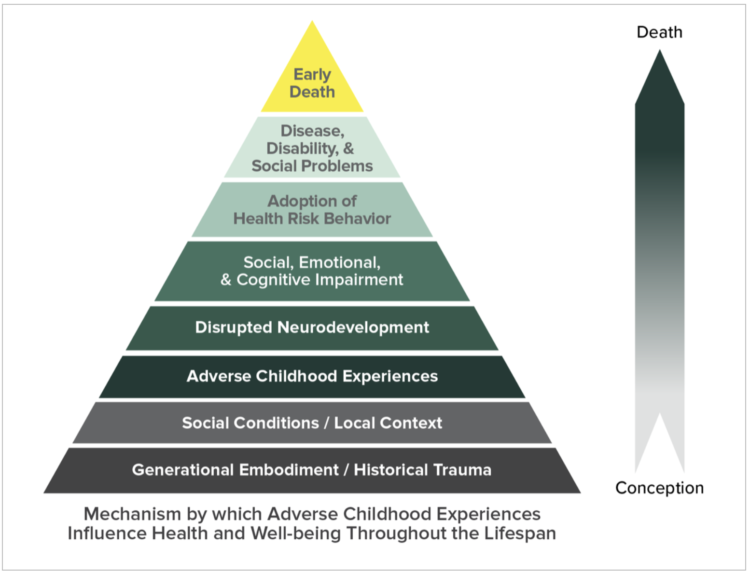

The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study is one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect and household challenges and later-life health and well-being. The 1995-1997 study linked childhood abuse directly to adult disease, showing definitively that as the number of adverse childhood experiences increase, so do the risks for negative health and life outcomes.

While the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have produced copious materials to help professionals, families and communities understand ACES, the United States remains mired in a Dominator Culture that, according to the Center for Partnership Studies, translates into:

- The U.S. is the only developed nation with no national funding for paid parental leave.

- The U.S. invests less than half as much in family benefits as other OECD nations: 1% of GDP compared to the OECD average of 2.6%.

- The U.S. invests one third as much on environmental protection as the European Union average.

- Among major developed nations, the U.S. invests the least in early childhood care and education.

Because Americans do not experience a wellbeing-oriented culture, it may be difficult for many of us to imagine how social supports through public policy creation could impact the country’s current devolution into a more authoritarian society. Even the CDC’s video We Can Prevent ACES focuses on recommendations like parent education and mentorship in communities, a microcosmic approach, instead of pointing to the macrocosm: missing social supports like healthcare, childcare, maternal care, and paid family leave enjoyed by every developed country in the world.

In this interview, Suzanne Zeedyk, a research scientist whose passion is to bring ACES science to the general public, shares how culture change is being driven by a grassroots vision to make the whole of Scotland an ACES aware nation. The country’s holistic approach to treating violence as a preventable disease led to a 50 percent reduction in violence in big cities like Glasgow over the past decade. In this podcast we hear Dr. Zeedyk share her experience of working with police departments, childcare centers, schools, and hosting an ACES conference of over 2500 attendees in 2018. As a leading ACES advocate, she helped the country’s grassroots movement gain momentum with local premiers of the ACES film documentary, Resilience. As an America citizen and long-term resident of Scotland, Dr. Zeedyk shares her insights on the possibility of bringing this cultural transformation to the United States, where ACES awareness is finding new champions.

In America, ACES Awareness is currently championed by California’s Surgeon General, Nadine Burke Harris, MD. You can see her TED Talk on ACES here and read about California’s efforts here. While America is beginning to recognize Adverse Childhood Experiences/childhood trauma as a risk factor and predictor of adult disease, the Evolved Nest Initiative helps us understand the neurobiological components and science-informed foundations of child flourishing and lifelong wellness. You can explore Darcia Narvaez’s award-winning research on our Evolved Nest here on Kindred.

It is possible, as Scotland’s success shows, for a nation to decide to become curious about the origins of violence, commit to the creation of a culture that supports wellness, and to share that success with other nations. For more on Scotland’s move toward a “wellbeing economy” watch First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon explain the far-reaching implications of prioritizing factors like equal pay, childcare, mental health and access to green space/nature connection. Sturgeon shows how this new focus could help build resolve to confront global challenges.

Scotland’s wellbeing perspective underlines the Scottish Government’s response to COVID. The National Child Health Commissioners, a group overseen by Scottish Government, have called publicly for a “rights and value-based response” to COVID, explicitly drawing attention to the impact of COVID lockdown on children’s relationships and attachment experiences as a result of stresses under which families have been placed.

In an upcoming interview with Riane Eisler, founder of the Center for Partnership Studies, Kindred further explores the social structures needed for the United States to move toward a wellbeing culture, and how the current pandemic is shifting our focus in that direction. Eisler’s Social Wealth Economic Indicators, a path forward for the U.S., can be found here. In a July 7 2020 Forbes interview, Eisler briefly outlined her plan for economic transformation.

Dr. Zeedyk is a developmental psychologist and Honorary Fellow at the University of Dundee. She began her academic career with a doctorate from Yale University. She is the creator of the film and educational project, The Connected Baby, and the author of multiple books on the science of human connection. As she shares with us in this interview, it is her passion and mission to bring the science of connection to parents and professionals who “deserve to know” this information so that they can feel more confident in taking part in a conversation about human relationships, healing and wellbeing.

Read Kindred’s articles on Adverse Childhood Experiences

Take the Adverse Childhood Experiences Quiz

Kindred’s ACES and Trauma Resources

NEW: Start your own ACES Initiative in America

Visit Dr. Zeedyk’s Connected Baby resources.

Listen to the Interview

Explore Interview Topics

Scottish Police Embrace a Holistic View of Violence as a Virus and Attachment as an Antidote

What Happens When People Become Curious About The Origins Of Violence?

The Role of ACES in Violence Reduction

Discovering Resilience, the Documentary, and the Start of an ACES Grassroots Movement

ACES In Childcare and Education

How To Talk About ACES Without Shame or Guilt?

Read the Interview Transcript

Scottish Police Embrace a Holistic View of Violence as a Virus and Attachment as an Antidote

“…they began to see violence in a new way. Rather than define it as a criminal justice issue they began to see it as a public health issue. They began to talk about violence in a new way: that violence is a disease that you catch from the stress in relationships around you, and therefore if it’s a disease that you catch you can prevent it, and that the key time to prevent violence is in those early years…”

SUZANNE ZEEDYK, PHD

LISA: It’s been 10 years since we talked about The Connected Baby, your film (the Kindred interview is here). If you listen to this interview, what you will hear is Dr. Zeedyk telling me that she has been working with the local police department on understanding attachment and childhood and how it related to, relates to violence in Scotland. Then, I couldn’t believe it. Now, what has happened? (See the video below) I couldn’t believe it back then, and now this holistic approach is responsible for a 50% drop in violence in Glasgow. Adverse Childhood Experiences, ACES, we call it now, attachment back then. So how did that happen?

DR. ZEEDYK: It’s a brilliant story and I am so glad you have asked. Let me embed that within my decision to step away from academia because I am a developmental psychologist. I study infant development, why relationships matter for the whole of your life and how they shape you become, your experiences in that early time, and I loved being a basic research scientist and at the same time I got frustrated because I began to realize that I had access to information that I thought was really fascinating and important about how babies develop and the wider world really did not have access to those publications, to those discoveries, and I thought they deserved it.

Human beings are wired in their brain and their bodies to form relationships, to expect other people. Babies who are in the womb in the last three months of pregnancy they can hear their mother’s voice, and the voices of anyone else who is in their world on a daily basis, so their father’s voice, their grandma’s voice, their big sister’s voice. I think that’s fascinating that you already know who’s going to be in your world. You can hear that through the wall of the womb, and you can pick up whether they laugh a lot or sing a lot or whether they shout and cry a lot. And your experiences of the tone of that voice and the rhythm of that voice and the hormones that will go with it.

I thought parents deserved to know, and social workers deserved to know, and childcare staff deserved to know, and police deserved to know, and politicians, and manufacturers of baby buggies, and I thought people deserved to know that stuff. So, when I last spoke to you 10 years ago I was in the process of stepping away from full-time academia to what I do now, which is to work with the public and try to translate that science for them, and the core message of that science for me is that babies come into the work already connected to other people.

For example, if your mother is producing stress hormones because she’s worried about life, because she’s in domestic violence, because her life is uncertain, she doesn’t have enough money, she lives in a violent neighborhood, she copes with racism. Those would produce stress hormones. If she was more relaxed and not scared she would have different types of what I call teddy bear hormones that help you to relax and feel comforted coursing through your body.

Watch Suzanne Zeedyk talk with Scotland’s Violence Reduction Unit about their insights into breaking intergenerational cycles of trauma, resulting in violence, through a holistic view of violence as a virus and the need for attachment for human mental and physical wellness.

Okay, by the time the baby is born the baby’s brain and body is already being wired, if that’s the right word, and some people don’t like that word so you think what word would you use to get across the idea that you are already born with an expectation of what your world will be like. Who’s in it? How stressful is it? How predictable is it? How scary is it? How safe is it? How much laughter will there be? That’s already wired in your body. I think that’s amazing. I think it’s endlessly fascinating. And then babies really tune into the way that other people respond to them and how they treat them and what that feels like, and that goes on to influence their biological development.

What I wanted to do was to help people understand that and to help us to think about what that means. So, when I spoke to you 10 years ago, I didn’t know if I would be able to feed myself even for the next year. Of course, it’s 10 years on and it’s really celebratory, so what I can tell you now is that people want to know this stuff. If you make science accessible to people they’re interested, they’re fascinated. They want to think about what it means for their individual lives, for these children’s lives, for their communities, for themselves and the experiences they were having as a child.

So, I’ve spent the last 10 years having good fun and lots of challenges to think how do you get and help people to think about those things. It’s something like, I don’t know, it must be heading towards 100,000 people have come to live events. Now, of course, we’re doing everything online; that lets more people come. I now have a small team. We produce resources that help people to get this and The Connected Baby was our very first one. So, I had made a film which set out to communicate that basic message, which is that babies arrive already connected to other people.

Public policy makers, police, social workers, teachers, childcare staff, all those people that I thought might be interested turned out to be interested, but they need the science to be accessible to them and described in a way that feels relevant and that doesn’t feel scary with big words that don’t make sense, where they don’t feel patronized and in fact where they can be brave and curious, because some of that science requires some real courage to engage with because once you realize how much your behavior as a parent is having on your child that takes a bit of courage to get your head around. If we don’t pay attention to the tone that we talk about that in, then parents understandably shut down because it’s too scary to think about.

LISA: In the last 10 years we were talking on Kindred about connection and attachment and prenatal science and now we have ACES, which is taking off, at least in discussions here in the states. This is important to know ACES isn’t the phrase used when watching your interview with the police. When did attachment discussions lead to ACES discussions?

DR. ZEEDYK: Can I go back to the police and just start there for a moment, because it helps to make it really relevant? Okay, so in 2004 in Scotland something unusual was happening. There were a couple of key members of the police who worked in Glasgow and at that point Glasgow was seen as one of the most violent cities in Europe because we had a high number of deaths by stabbing. In Scotland we don’t have… guns are not allowed to be owned by the general public, and so in America you have a lot of shootings and in the key parts of Scotland we had a lot of stabbings.

A lot of that came from gang violence, but it was also intergenerational, so families where members had died or gone to prison, their children went to the same prison, their children went to the same prison and they were housed on the same street. It was just generation after generation, and eventually these two key members of the police said, “You know what? We’re just locking people up. We’re not reducing crime. Couldn’t we do something different? Is our role as the police to arrest the bad people and lock them up or is our role as the police to actually prevent crime and indeed prevent violence. Violence in all its forms, not just criminal violence.”

That’s a really radical thought. Their names are John Carnochan and Karen McCluskey and they convinced their boss to allow them to have some time to think about the violence problem in a new way and to start to talk to people that would give them ideas about what are other ways you could approach and prevent violence.

If they had not had the time to do that thinking and they had not had the support of their divisional commander, we wouldn’t be where we are in Scotland today. I pause to help us to think about the importance of leadership and the importance of curiosity and the importance of thinking outside the box.

At that point I didn’t know about the Violence Reduction Unit. I heard about their third-hand. I thought it sounded like they were doing some really fascinating things. They had begun to talk about the importance of early years, the idea that police were talking about babies. I thought it was a great idea.

I actually got approached to critique that idea, that police should not be doing that, and I disagreed and so I wrote to them and said,”I don’t know who you are but I just want you to know that I think that this is a really creative important idea that you’ve had.” So John and Karen called me and said, “Could we come and talk to you about child development?” And therein started my support for the Violence Reduction Unit that has lasted to this day.

I flagged that because that becomes important to coming back to what is happening now 15 years on. But it’s worth thinking about, How do you get a police department that’s interested in babies? They got really criticized for that. People just said, that is not the roll of the police, and you know, that’s a fascinating question. What is the role of the police and who decides what the role of the police is, and what happens if the police decide that their role is to try to prevent violence rather than just cope with its consequences?

The route that they went down, they began to see violence in a new way. Rather than define it as a criminal justice issue they began to see it as a public health issue. They began to talk about violence in a new way: that violence is a disease that you catch from the stress in relationships around you, and therefore if it’s a disease that you catch you can prevent it, and that the key time to prevent violence is in those early years with predictable, warm relationships that feel safe and that will not wire young human beings for stress and anxiety, but that will wire them for internal safety so that you can handle things like uncertainty, anxiety. You can trust people. You can stay curious. If you’re wired for anxiety, all of those things are harder.

What Happens When People Become Curious About The Origins Of Violence?

“…the crucial opening is people who are willing to get curious and to give up blame. And that’s part of what the Violence Reduction Unit was able to do. They were able to help people to be more curious and the science of adverse childhood experiences and attachment are some of the things that helped them to do that.”

SUZANNE ZEEDYK, PHD

LISA: So, if we had this mentality of providing the connection at the beginning, as a preventive measure to create wellness, this could change the population. Is that what you saw?

DR. ZEEDYK: Absolutely, that is where the thinking about understanding these key links and how relationships work on the body, that’s exactly where it takes you. So you… what you start to realize is that cultures are shaped by the way parents raise their children, by the way parents are able to raise their children, because parents can’t raise their children on their own. Parents raise their children in communities, so if you have communities that are really stressed, parents are stressed. That’s inevitable. That’s understandable, and if parents are stressed then children pick up on it and children become… their biology becomes tuned to stress because that’s how child development works.

You are in unconscious attunement to the people who are crucial in your life. Robin Grille, who’s another Kindred contributor, talks a lot about that. So, he in his fabulous book Parenting for a Peaceful World, I talk about that book a lot in the work I do. He talks about analyzing Nazi Germany, and he traces back the rise in Nazi Germany to the kind of advice that was given to lots of German parents in the period of time before the Nazi rise.

In other words, why… how did Hitler gain power? Why was he not just treated as talking crazy stuff? Sometimes people talk about the economics of what was happening. Sometimes people talk about the international relations at the time. Well, Robin Grille talks about how children were raised and how your ability to tolerate uncertainty makes you susceptible to particular kind of messages and what Hitler promised was that he would save people from the enemy. That was one of his messages.

He created a “them” and an “us” and that he could protect you from the “them.” So, if you’re wired for anxiety and you don’t even know that, it just feels like normal to you and a whole lot of other people in your community too, then it puts you at risk of people promising to bring you safety, but that bring with it all sorts of other consequences. Robin Grille traces that kind of history when he talks about Nazi Germany and he traces that in a number of other cultures as well. That’s a really big picture vision. It speaks to me of just how important the way we care for our children is.

The police in Glasgow got interested in what kind of caring were lots of children in Glasgow getting. What were their early childhoods like? And that became part of the new strategy that they brought to thinking about violence. They thought in terms of gang membership as membership, as meeting the needs for relationship. They thought in terms of purposeful lives, so if people don’t have jobs and they don’t feel part of the wider community, then human beings because of our attachment system which we’re biologically endowed with; we want to belong, so gangs are a good place to belong to.

If you have stress in your early childhood that makes it hard to manage your emotions, if the people around you who are part of your tribe, a gang, are engaging in violence, well then that just comes to seem normal to you and so they began to ask lots of questions, fascinating questions, about what are the roles that human need for relationship is playing in the violence problem in Glasgow and to skip 10 years into the future through a variety of strategies but all embedded in understanding relationships and support and helping people to feel worthwhile and valued, they’ve cut the rate of violence in Glasgow by 50%.

With all the costs in doing that, with reducing those with saving the sadness of human lives of people who are lost and the way the grief ripples out, they have really been able to make an impact on the violence in Glasgow. Just this week, there was a journalist who covered the history of the Violence Reduction Unit on national television here in the UK because she was trying to tell the story of how Scotland reduced violence because she’s hoping that the same types of insights might have an impact in London where the rates of youth violence and stabbing are very rapidly climbing. Trying to help other people to get curious about how Scotland did that and began to see policing differently and violence differently, that’s one of her goals. It’s an interesting challenge to try to help people to be willing to define violence through public health lands as a disease rather than just about what bad people do.

LISA: This video that you just posted recently, is it 10 years old, the one where you talk about violence with crime unit heads.

DR. ZEEDYK: Yeah.

LISA: It’s a beautifully done video, by the way. I found the most remarkable part is John Carnigan, and how he leads with curiosity, clearly as a seasoned investigator and police officer, and he says murders and suicides are not “happenstance.” They are not usually premeditated.

When he becomes curious about what is it that’s going to predict violence? What is contributing to this pattern? And to hear him articulate the connection between childhood and the violence that they are trying to prevent – and this was a 10 year old interview – but it is completely relevant and remarkable to watch today.

I felt like this is the crack. This is the crack in the wall of resistance to a new worldview. It has to be curiosity. We have to breathe, pause, and allow something in ourselves to open up and make room for the possibility that there can be another way to approach violence. That word that he uses is a very Scottish word: violence is not premeditated; it’s “happenstance.”

DR. ZEEDYK: He absolutely does say that. He and Karen, who is the other person interviewed in the film, and they are the cofounders of the Violence Reduction Unit, and as they would both say, it’s the Violence Reduction Unit. It’s not the Violent Crime Reduction Unit, it’s the Violence Reduction Unit. So, they are interested in domestic violence, racism, community violence, bullying, child abuse.

They began to see the scope of what they were doing as about violence in much more broadly defined than just criminal violence, and that then allows them to see that if you go back to the gang warfare in Glasgow, they would describe it that it’s just as likely that you would be the young man ending up dead as you were the young man doing the killing. It’s happening in particular communities, the communities that are stressed. That doesn’t mean that the gang activity is happening in particular communities. I think one of our problems is we can go, “Well, it’s those communities over there and if I’m safe in my community I don’t have to think about that community.” But part of the message that they were trying to say is that there is no them and us.

What happens in one community ripples out to other communities, so for instance, taxpayers pay to put people in prison, right? Taxpayers pay for educational systems. If children aren’t benefiting as fully as they might from those educational systems, the taxpayers’ money got wasted. I suppose one response to that is, “Yeah, well, I don’t want to put my money into educating other people’s children. I don’t want to put my money into childcare for other people’s children. I’m perfectly happy to have people locked up in prison as long as my family is not at risk.”

So, we can respond to that in a fear-based way and move further and further and further apart so that we’re all living in our own little prisons because we’re scared of each other. A society can absolutely get to that point. You’re going to have to put a lot of money into protecting yourself from other people. Your life is going to be much more restricted, in other words. And you can think of all sorts of ways in which a life based on fear looks like, or you can get curious about seeing new ways and making connections.

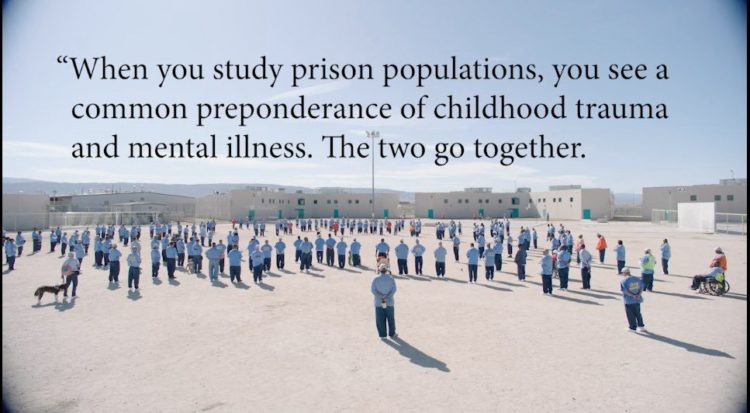

I think of it this way. If you just come back to the criminal justice issue, it turns out that children who live scary, stressed lives early in their childhood become wired for anxiety and that makes it harder for them to manage their emotions and manage their behavior. So, prisons are full of people who lead traumatized childhoods. I sometimes call prisons warehouses for traumatized people.

LISA: There’s a documentary out now based on ACES in prisons. (See the documentary trailer, Step Inside the Circle here.)

DR. ZEEDYK: Yes, there’s a documentary out for ACES and in fact there are a lots of people who have become interested in what happens with a traumatized childhood. ACES, Adverse Childhood Experiences, is one of the latest ways to frame what happens with a childhood where you feel stressed and scared and you experience lots of trauma. And I can come back to that in a minute if you like. But it raises a very interesting question: What happens if prisons are full with people who experience chaos and trauma when they were children. How does that change our understanding of what the prison system is doing, what happened to have people get there, and are we willing to get curious about that or are we so attached to blame that we’re willing to pay more money for it, we’re willing to cause more misery for it. How much are we willing to pay in order to stay attached to blame bad people?

If we are willing to shift to a place of curiosity there are all sorts of other solutions that are possible that cost less money and that help people lead fulfilling lives. For me, the crucial opening is people who are willing to get curious and to give up blame. And that’s part of what the Violence Reduction Unit was able to do. They were able to help people to be more curious and the science of adverse childhood experiences and attachment are some of the things that helped them to do that.

The Role of ACES In Violence Reduction

“I see ACES as a continuation of the attachment work… We didn’t have an attachment movement. I think that we have an ACES movement in Scotland because that film, Resilience, helped enough people to understand the science in a deeper way…”

SUZANNE ZEEDYK, PHD

LISA: So, I want to go to a more thorough look at ACES, but before I do that I just want to tell our listeners that you can go to Kindredmedia.org and there is a trailer and you can go to links for the documentary on ACES in prison, which is called Step Inside the Circle. It is a fairly new documentary.

I would like to go back to the Adverse Childhood Experiences, ACES, survey that was done that is being used now as a tool to focus people’s attention in a very concise way on the connection between childhood and lifelong wellness or illness. How’s that tool been fashioned and how’s it being used right now?

DR. ZEEDYK: Let me go back to the science for a moment, in fact let me go way far back with the science. In the 1940s, scientists like John Bowlby and James Roberston, here in the UK, began to realize in deeper ways the importance of relationships, and that children were being shaped in really deep ways by the experiences of their mothers and their fathers and other people in their lives and that lead to what is often seen at attachment theory.

A lot of people did work on attachment theory for a number of decades, and that has an interesting history in and of itself. And when I talked with you 10 years ago, I was talking a lot about attachment. Adverse Childhood Experiences, the science framed that way, the first publication was done in 1998. In other words it’s been around for about 20 years.

I see ACES as a continuation of the attachment work. That publication was done by two scientists, Vincent Felitti and Robert Anda, and the key insight that they had, that they were talking about and that they wanted a wider understanding of was that they had data that showed that if you had had stressful chaotic things happen in your childhood like domestic violence, a parent who was in prison, a parent with mental illness, a parent who used substances, parents who were divorced, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, that they could track with a correlational design an impact on adult health problems. They were able to show a relationship between childhood trauma and heart disease, liver disease, diabetes, as well as alcohol addictions, drug addictions, as well as mental health difficulties like depression and mental health disorders. They did that with a really big sample of 17,000 people so it was really robust and they published that in 1998. Then a number of other studies have followed since then.

In 2014-ish James Redford, who’s a filmmaker, got frustrated because he knew about that study and he thought that the wider public should also know about that study. And indeed we had been talking about that study in Scotland. It was part of what the police department were talking about. It was part of the way they explained how violence could carry on, but it was one of a kind of whole variety of pieces of scientific evidence that they were using to talk about.

In 2014 James Redford begins to make the film that becomes the Resilence film where he’s talking about that science, and in 2017 we showed that film in Scotland. At the time we just saw it as a tool, as one more tool, for helping people to understand ACES and that study, but to understand the impact of relationships more generally. What I had not predicted was the impact that that film was going to have. It has a dramatic impact here in Scotland and people began to get in new ways the impact of relationships on childrens’ development and especially scary experiences.

If you don’t have a reliable safe relationship in your life to help you with your scary experiences, then you become more wired for anxiety. You become hypervigilant. You have what I call a sabertooth tiger moment, i.e., you become wired for the fear of death at the extreme. In other words, your body is wired for stress and worry and threat.

How do you help people to understand that? Well, that film had a dramatic impact here in Scotland and what I learned from it was something really important. You can have lots of science that is useful to people and that I think they would be fascinated by, but that very often the science does not leave the journals on it’s own. I think we need to think more deeply about how you translate science for the wider public. Because now there is an ACES movement, and that film has certainly helped here in Scotland and the UK and in parts of the US.

We didn’t have an attachment movement. I think that we have an ACES movement in Scotland because that film helped enough people to now understand the science in a deeper way and that has led to all sorts of other public responses and a tremendous amount of interest here in Scotland, and that film was the crucial thing that helped to gather momentum. And so I think we need to think harder as scientists about how we translate key scientific discoveries. We need to think about how we reach the public with those.

Discovering Resilience, the Documentary, and the Start of an ACES Grassroots Movement

“People belong to a nation. We wanted a vision for what could our nation be like. What kind of values do we want? What do we want for its people? What do we want for our children? Our children! In other words, it’s not them and us, it’s our children.”

SUZANNE ZEEDYK, PHD

LISA: In the United States, Nadine Burke Harris, MD, who is now California’s Surgeon General, is trying to lead a movement of ACES awareness in that state, and she wrote the book The Deepest Well to try to help people understand ACES. She talks about one of the biggest hurdles she found is that she would present the science at conferences, and she said that no one was interested, that the participants in academic science, there were just crickets after her talks. Then she would go down to her table to pack up her books and get ready to leave and the people that were interested in her talk were the people who were working the conference, people who were waiting the tables, and putting together the event. These people came over to her and said, “I heard what you said and I want to know more about this.”

I think in her mind, and certainly in mine as an activist for the last 22 years, the gatekeepers of science do not help average people understand the science. In my work, I have focused on ways around some of the institutions that seem to want to be gatekeepers for parents, who just want the information so they know what is the best course for their children and the best decision to make, and certainly how to create a culture that would be life-affirming and attachment-oriented. But we don’t seem to get that information through the gatekeepers.

DR. ZEEDYK: I think it all starts with curiosity. So, I work with a lot of organizations myself. So, I’ll work with anybody who wants to talk about what I call “this stuff” in order to help us, so it’s not so scary. I think everyone deserves to know this stuff. If I’m addressing an audience of nurses or I’m working with a school or I’m talking to doctors or to politicians, in my head I remember that in this audience there are mothers and fathers and grandparents and sisters and people who were once children, because if you get people interested at a personal level they listen to that information in a new way. So, I never ever forget that I’m talking to individuals who have the capacity to be curious. Then individuals bring their curiosity to organizations and to communities, and if you can help people to feel confident then they act on it. That’s exactly what happened with our ACES movement here, is that when… let me just tell that story to help people to a vision or what happened.

It was two tiny organizations that decided to show that film. One of them was mine, Connected Baby, and another is an organization called Reattachment which worked with kinship carers and foster carers. That organization was led by a woman named Tina Hendry. Tina and I worked together and we knew the film was coming so we said to the UK distributors, could we show that film here in Scotland and they said sure. We said it will be the first time, and we’ll call it the premiere. The Scottish premiere, which it was.

We gave it a big name and it becomes really interesting to go, what should you call it? Should you call it a premiere? Is that too big? Well, it was and we wanted to celebrate it. We only thought it was going to be one screening, so we put it up on social media. We booked a cinema, and I didn’t actually know that you could book a cinema at that point. It turns out that you can. You can rent the space like any other space. We hoped that we would sell enough tickets to pay for that space. We had no money and we just took a risk. We thought it was important enough to bring to the wider public, we were willing to take a chance on it and it sold out.

In a few days all the tickets were gone, which stunned us. Then people began to write to us and say, “I couldn’t get a ticket to that screening and you’ve got no extra tickets. Could you not bring that film to Edinburgh?” Which is another city here in Scotland, and we went, oh we hadn’t thought about that. Well, okay I guess we could. So we booked another cinema and the tickets sold out and then people said, well could you bring that to Dunfermline? Couldn’t you bring that to Inverness? And before you knew it we found ourselves in the middle of all of this clamour to see that film.

We had not anticipated it. We were exhausted by the end of the summer; 2500 people came to see that film in 25 different locations in Scotland. We ended up booking church halls, community centers. One one occasion we showed it in a childcare center with people sitting on the floor.

So, I’m trying to tell the story of a totally organic community movement and then the crucial bit was people went back to their organizations and said, you have to show this film. They wrote to their local like city government and said you have to purchase this film. You have to get a license for this film. All the teachers who work in this city deserve to see that film, and they just badgered them. We had no anticipation that that was going to happen. Suddenly, that film was everywhere around Scotland. People were following us on social media in England across the border said how can we get a hold of the film?. People in Northern Ireland got in contact and said do you think we could do a screening like that?

My little team at Connected Baby said, sure we’ll help you do the posters. Before you know it there was just this explosion of interest and I tell that story a lot now because it helps to show there was no plan. We had no money. The government was not in charge of it. Now, that’s an interesting point because here in Scotland the government, or local government, or national government is often seen as organizing these things. So, lots of people assumed that the government would be in charge of it. We did get the national public health organization to help us to distribute knowledge of it, and because they were putting work in their logo went on our poster, but they weren’t fronting it. They didn’t put in money. In other words it was entirely community led.

I tell that story because I hope it might inspire other people to think, okay we could do that. Because that has happened in a number of places in America where people are talking about ACES and there are several key websites now, so ACES Connection is one of them, where people who come to understand, know about ACES, and want to talk to other people who are trying to do things are coming together. I tell the story of what happened at a community level here in Scotland so that other people will know that it is possible.

Now in America, people are much more divided about what the role of government should be. In fact if the government were doing this, some people will be highly suspicious of it, and people think that private organizations should be the sort of organizations that would fund this. That’s a really interesting question. If you have science that is useful to people, how do you get it out to the public. Who funds that? What happens if nobody funds it?

How do you talk about debate around it, because we could come back to there’s some big debate around the ACES model now and there is some big debate here in Scotland. Not everybody is in favor of that way of thinking of human experience and development. What do you do if there’s a big debate if people aren’t trained in scientific methods? How do you help them to get more confident and more curious?

I have become really fascinated by that process of translating science for the public. What is the story behind what happens? I presume that at some point in the future, the story of how the film Resilience came to have such an impact on Scotland. It might be forgotten. People may have no memory that it was done by two little tiny organizations that had no money. Those sorts of things can get lost in the detail, and yet knowing the story helps to inspire people who want to make change in the area. Nadine Burke Harris called her book The Deepest Well. Nadine Burke Harris is in that film, Resilience. And in fact after that film tour with another organization here in Scotland that are called Tigers, and they work with young people to help them to find jobs, and I do work with them. They’re run by a woman by the name of Pauline Scott, so I presume at some point she and her team might listen to this. They also run a nursery called Lullaby Lane.

So, Pauline and I were thinking about what are other ways that we could help people to think about ACES and relationships. In other words not just the experiences that happen to children that are in the scoring system that ACES uses, but to actually think about relationships. Not just the kinds of events. That’s been really important here in Scotland, to keep relationships at the center of our thinking. So we said, do you think Nadine Burke Harris would come? Lots of people have seen her in the film. She was good in the film. Do you think if we emailed her she would come? So, basically over a glass of wine we went, well we could email her. I hope she’s listening to this. We could email her and she’ll probably say no. We’ll probably not get her. She’ll probably have a team. We haven’t got any money. How would we pay for her? Well, if you don’t email her we’ll never know. She probably…give her a chance to say no.

She didn’t say no. Did you know, she and her team emailed us back and said okay she would come. I will never forget the night that we got the email. It was late at night. I text Pauline and said, are you up? Are you up? I have to give you this news. The vision that she was then able to bring…in other words she could bring a bigger vision for how she was talking about ACES, what she was trying to help people to do. She wasn’t yet the Surgeon General in California then. So, Pauline and I said, let’s have an event. Do you suppose we could get 500 people to come? What kind of venue do you need to hire that has 500 people at it? That’s a big venue in Scotland. Before we were done 2500 people came.

LISA: I just find that so awesome, remarkable.

DR. ZEEDYK: So the idea that there are 2500 people together in a big room wanting to talk about childhood trauma and the importance of relationships was massive. It wasn’t led by a multinational corporation with lots of money. It wasn’t led by the government. It was led by two small organizations who took a risk and who said I think we can do this if we thought creatively, and luckily we could just keep booking more tiers of seeds, otherwise we would have had to cap it. So, luckily we had a big enough venue that let all those people come. People would not have come to see Nadine Burke Harris if they hadn’t seen the film because they wouldn’t have known who she was.

LISA: Yeah, okay. Wow.

DR. ZEEDYK: Okay, and then we developed…we began to develop a vision. We began to talk about could we be the first ACE aware nation in the world? Could we reach every single citizen of Scotland. There are five million. Now by American standards that sounds crazy. There are lots of cities that are bigger than five million people, how can you have a whole nation with only five million people? Well, you know what? That was part of our strength we thought. Could we, in other words, we talked about a nation, Lisa. People belong to a nation. We wanted a vision for what could our nation be like. What kind of values do we want? What do we want for its people? What do we want for our children? Our children! In other words, it’s not them and us, it’s our children.

So we began to put the science of ACES into a bigger vision that was about belonging rather than simply disperse information about trauma, we were trying to use it to envision about who we wanted to be and to have big conversations about that. That energy still continues. There are people who think, should we be doing more? Who should lead that? Is it going fast enough? What if people disagree? All of those are important questions. Some people are uncomfortable about the debate, so here’s where some of the debate lies.

Should we be scoring trauma on a 10 point scale. That is how Felitti and Anda developed their original ACES methodology. Nadine Burke Harris has developed a particular kind of screening tool that she uses with pediatricians. She has a view that she has developed over time in trying to make use of an ACES frame in the way that she thinks about health and the way that she thinks about violence in neighborhoods and the way that she thinks about racism, and the vision that she has for the change that could happen in California. We were not having those kinds of big discussions in Scotland before the ACES frame came along. So, although some people really do not like that scoring, some people really do not like that the first original publication by Felitti and Anda in 1998 was with a middle class sample. They think that it should have been more representative with a more diverse class/classes and more diverse ethnic makeup. Now you can have very interesting discussions about what are the limitations of a particular design that still make the findings that it produces worthwhile and valuable.

The key point for me is whatever debate one wants to bring to ACES, we were not having a public discussion about childhood trauma before the ACES frame came along. So, there is something valuable about the ACES frame that helps people to step in and become more curious.

I am grateful every day now for that debate, because I think children have a right to have safe, reliable relationships. I think they have a right to expect adults who are curious about their emotional needs. I think we have a moral responsibility as adults to offer that to our children, and I hope that the science helps more adults to get curious about that as well.

We pay terrible prices when children in our communities experience uncertainty and fear and chaos and if families struggle, for whatever reason, to meet the needs of their children, then schools can step in and do a lot as well. So, there are full ripples if you understand the key idea that scary childhoods change your biology and that has consequences for the people around you.

ACES In Childcare and Education

“Evolutionarily, the evolution and history of the human species, children hung out with their tribe, with their extended family. So from a child’s perspective, childcare staff are part of their extended family. They are Aunty Mary and Uncle Jason, Grandma Molly, and so if they come to feel, if they come to love that person, if they come to like their company and miss them, if you move them to a new childcare setting and they never see those people again, that’s a bereavement.”

SUZANNE ZEEDYK, PHD

LISA: I want to tell the listeners that we have the Find Your Score – ACES quiz on Kindred as well. It is one of our most popular pieces on the website. In fact every time I tag something as ACES people go right to it. Evidence that people are finding out about it and they’re very curious.

But, before we go away from the how are ACES and this piece playing out in Scotland, I did want you to touch really quickly on childcare and schools because I have seen your presentations on YouTube, where you’re speaking to an audience of childcare providers, and I absolutely adore and deeply appreciate the way you present, because you’re very courageous saying, “To not be aware of attachment science is to cause damage.”

You just put it out there: “You’re not going to like this.” You’re reading the audience while you’re saying this, “Some of you are shaking your heads.” You’re very aware of their response to what you’re bringing. The part that I found to be remarkable and just heartwarming is you explain the point of view of the child and that going into a childcare facility if you told the child these people are being paid to care for you they would be appalled. No, they love me and I love them, they believe. And to have a policy that says you have to move the child around and then you break relationships all the time unaware of the importance of this childcare provider, what significance they have in this child’s mind, and the impact of that on their biology and lifelong potentially, to just have that kind of disruptive policy and pattern in place.

DR. ZEEDYK: Yeah, I do put it that way. If you state things in strong ways, edgy ways, people pay closer attention to what you just said because they’re uncomfortable about it. The tricky line is to try to say it in a way that helps them to pay attention without tipping them into guilt or shame. Anger is even better than guilt or shame.

So, how do you help us to think more deeply about the importance of relationships? There are tons of people who are trying to get out this information. Other names are Bruce Perry, Dan Seigel, Dan Hughes. I have already talked about Bowlby. There are lots of people… Darcia Narvaez. I could name lots of people who have tried to help the wider public to try to understand the importance of relationships. But clearly there’s a struggle, because some of the things I state are still a surprise to people, like childcare.

In America, childcare is not funded by the government, and maternity leave is not even funded. It’s not a federal requirement. Okay, that must mean that either we don’t understand how important those early years are or we just haven’t heard the science of that, or that we don’t really get how important they are or actually we don’t care, the people in power don’t care or don’t really get it.

Here in Scotland we have maternity leave that’s funded by the government. We have childcare that’s funded by the government. In fact we just expanded the childcare provision here in Scotland over the last few years so that you… for children between three and four especially, have 1140 hours of government paid childcare a year. The government pays for that.

Although there is some debate about that, one of the things it does is it helps parents in terms of employment. Some people think that actually we should be using that money in other ways to support parents to stay home with their children, and that’s another debate.

But the question that you’re asking is, okay so children, including babies, are cared for by people that we call childcare staff. If children come to love those staff, and children are wired to love the adults that they spend time with, they’re wired to do that biologically. They don’t know that they’re paid to take care of you. They would be appalled if they knew that. Young children think that you’re there because you love them. Otherwise biologically they don’t know why you would be there.

Evolutionarily, the evolution and history of the human species, children hung out with their tribe, with their extended family. So from a child’s perspective, childcare staff are part of their extended family. They are Aunty Mary and Uncle Jason, Grandma Molly, and so if they come to feel, if they come to love that person, if they come to like their company and miss them, if you move them to a new childcare setting and they never see those people again, that’s a bereavement.

Now if we were in a room together, I would say the word bereavement and then I would said for everybody to take in a breath because it’s scary, so I would say it in a very soft voice because it’s going to be hard enough to get your head around that because there’s going to be parents in the audience who suddenly see the implication of the fact that they moved their child’s childcare without ever thinking about that. They’re suddenly thinking, would I have done that if I had heard her say that before? Then people are going to have to decide how they feel about what I just said. Some people might get angry. Some people might go to a place of guilt. What I want to do is help us to get curious.

So, let me move to the last few months. Here in Scotland we went into lockdown because of COVID. So almost overnight childcare settings closed down. Schools closed down. So, children went home to be with their families and they missed their childcare workers and staff and because we call them workers and staff we grownups think of them as employed to do this. We don’t think of it through the child’s view.

Some nurseries who really got this attachment view under their belt worked hard to stay attached to those children and connection with those children. They sent videos. They sent letters. They put on videos of the songs that they sang. They took videos of the toys that they had been playing with. They took videos of the children in their garden. They sent keyrings home with pictures of their key staff.

Spontaneously, the children of those parents began to send back videos of the children responding to the videos, to the keyrings, to the letters. So one of the things that has happened here in Scotland… and some of those were put on social media. People have been able to see, even babies, you know 10-month-olds, children who are not talking yet, light up at the sound of that person’s voice, get really close to the screen with the video of that person, so you start to see the connection that’s there that lots of people might assume, well the children won’t remember because we can’t remember consciously as adults back to those early times so we have this idea that children forget. Children don’t forget.

One of the phrases that often gets used a lot in the trauma world is that the body keeps the score, meaning that the body remembers what you don’t always remember consciously. If we coped with a lot of grief and a lot of uncertainty because we ended up at several different childcare settings when we were young, that will have left traces on our bodies in ways that our parents never meant to. In ways that the childcare staff never meant to.

If you’re setting up these children to cry a lot, and there’s lots of people who think that if we just ignore children’s crying they’ll learn to not cry, children cry because they are trying to express that they need something. So, if the childcare staff ratio is too high to attend to the needs of those children, then those experiences are shaping children’s attachment experiences in the same way that they would be experienced at home.

Being able to think about the importance of those early years and the importance of the kind of care that we provide in those early years, it really really matters. If you haven’t got the idea that those early experiences are going to change you biologically, people just don’t even know to get started with those kinds of questions.

How To Talk About ACES Without Shame or Guilt?

“Rather than telling people how to parent, which pisses a lot of people off, what I try to do is to help us to understand how children and babies develop so that we can get curious about what they need rather than to be told how to parent them. So that’s the approach that I try to come at this, and what I find is that if people don’t feel shamed, bossed, pressured, they step in with curiosity. In my experience people really want to know this stuff.”

SUZANNE ZEEDYK, PHD

LISA: I want to segway here into how do you appeal to adults? Because families who try to do attachment parenting in America are considered counter-culture, and there are a number of organizations I have worked with over the years who have developed community groups and support groups and gathering groups for parents who are interested in attachment, but even parents who are interested, when I would go present to them, you could see that the language… I would have to be careful about the language because of the guilt and shame and fear that is so ready here in American society to pounce on parents and really pummel them. I appreciate that you have the Tigers and Teddies program, which I would like to hear you explain how that kind of goes in the side door and skips all the shame and fear, and then I would love to hear about your book as well, The Little Iceberg.

DR. ZEEDYK: Okay those are great questions. If you come back to how do you talk about this stuff in a way that doesn’t make people feel guilty and ashamed and pressured but helps them to be curious. I often use metaphors because it helps people to get ideas, and I found myself trying to talk about what it’s like to feel comforted and safe and I found myself talking about the experience that you have with a teddy bear, they are like teddy bear moments when you feel safe and relaxed and comfortable and when you get scared and you feel threatened it’s like the saber tooth tiger were chasing you.

I pulled saber tooth tiger out of the air in those early days because it’s easy to imagine the great big teeth. I now talk about saber tooth tigers and teddy bears all the time as a metaphor for helping us to think about the experiences of threat and of safety. That metaphoric language helps to get it immediately. There is no other purpose in a teddy bear than to help you to feel safe and comforted. But it actually helps us to think about real teddy bears.

Real teddy bears matter to children because they help them to feel safe. So lots of children want to take teddy bears with them to childcare. What happens if you don’t know that those teddy bears are really important and you just see it as an object ,and you say something like, we don’t want you to lose your teddy bear so we’re going to leave it here in your basket at the door, and you don’t know that actually having the teddy bear with you, under your arm so that you can feel the fur, so that you can feel the warmth, all that sensory familiarity is part of what helps you feel safe and helps you to learn at childcare or helps you to make friends at childcare, that helps you to feel confident in the world.

Teddy bears do that for young children. I want to use teddy bear language as a metaphor for what is feels like internally but also to help us to think in light and yet serious ways about what are the ways that children feel safe, and teddy bears is one of those. So when children have that meltdown… okay, my nine-month old was perfectly happy, I left them in the hall, I just wanted to go to the bathroom and they were playing with all their blocks and they were fine and I shut the door and they started screaming at me, mommy, mommy, mommy, mommy. All I wanted to do was go to the bathroom. It’s what I call a saber tooth tiger moment.

From an adult perspective you think, why is the kid screaming at me? If you feel totally beleaguered by your child screaming at you when you come out of the bathroom if you speak sharply to that child because you feel overwhelmed… it’s totally understandable… raising kids is hard. But if you speak sharply every time you come out of the bathroom, the child starts to expect the reunions with you will be full of anxiety and they become wired for that. They grow into that biologically. They get anxious about their reunion with you and that starts to shape their attachment style.

How do you help parents to get curious about why their child is crying when it makes no sense to you, especially if you feel accused by the child or you feel irritated by the child, or actually you are quite happy to pick up your child and rock your child and you don’t understand why the other parents aren’t? All of those are saber tooth tiger moments.

Any emotions that are difficult for us I think of saber tooth tiger moments, and that’s because they’re drawing on the part of the stress system in the human body that are there to help you to deal with difficult moments. At the extreme end that would be running away from a saber tooth tiger. At a less extreme end that might be sitting at traffic lights. You know, sitting at traffic lights doesn’t cause everybody stress but it causes some people stress because then they go into road rage. So managing your emotional system is part of stress. People often don’t think of emotions as part of our stress system. Yet, when you stop to think about it that’s exactly what they are. If you have experiences that wire your body for saber tooth tiger moments, then you find it harder to regulate your emotions. That comes out in your behavior. Attachment experiences shape that emotional system.

Once upon a time, attachment scientists saw attachment in a cognitive way. It was about your expectations of relationships, your cognitive working model, or they saw it was about behavior. Nowadays, attachment scientists see attachment as about the emotional regulatory system. So that’s where it starts to overlaps with ACES. If you have experiences of adults that are predictable and safe, then it wires you biologically different than if they are chaotic.

What I try to do is to find ways to help people to think about that in a curious way rather than in an accused way. So we just this summer released the second edition of my book called, Saber Tooth Tigers and Teddy Bears, the Connected Baby Guide to Attachment. It’s purposely written in an extremely accessible style. It’s not a big fat book. It’s got lots of photographs in it so that it makes these ideas accessible to anybody and I now have people who write and say, “Your book changed my life because I can now see my own childhood in a different way. Your book has made me rethink my mother’s childhood really deeply in a way I never thought about.”

This makes me think about how we could bring this information to schools or to police or to criminal justice. So what I’ve tried to do is to make those ideas really accessible to everyday life. In it I tell stories. I think that’s my favorite part of it. I tell stories of real people who put this information to use. So I tell the story of a lawyer that understanding attachment and ACES changed the way that he argues the case for people who are accused of crimes. He’s changed the way that he presents those cases to judges. He talks more about the trauma in their childhood.

I tell the story of a bankrobber. I tell the story of the schools who spent part of their school budget on purchasing lots of teddy bears so that the teddy bears are there when the children walk through the door because they know that many of those children will have left chaotic households that morning. I tell the story of a parent who said I didn’t use to know this and now I’m better able to support my child who’s really anxious and I probably helped to cause some of her anxiety. I didn’t mean to and I didn’t know that now, but I can forgive myself for what I didn’t know and I can get curious about how to help her now.

Rather than telling people how to parent, which pisses a lot of people off, what I try to do is to help us to understand how children and babies develop so that we can get curious about what they need rather than to be told how to parent them. So that’s the approach that I try to come at this, and what I find is that if people don’t feel shamed, bossed, pressured, they step in with curiosity. In my experience people really want to know this stuff, and metaphors like saber tooth tigers and teddy bears give us a light way of engaging with those questions.

LISA: That is a fantastic tool, and I am so very happy to hear about it and as you were saying the parenting piece is so tricky because of the prescriptive nature of it. We have a lot of those in the United States that don’t look at the attachment science. I think it’s exactly what you said about what happened in Germany when you had the authoritarian style parenting in place and then you have a dictator come into power and people who follow him and you’re wondering how could this happen? But one preceded the other.

This piece that you’re bringing in, giving parents tools to be present in a way that they want to be present and curious is just remarkable. I know we’re about at the end of our time, but I did want to talk just for a moment about your The Little Iceberg book because it is also a glorious book and tool. It’s not just a children’s book. It is also a metaphor and it comes with a little book on the side that tells you what’s really going on in the children’s book so the parent or the educator, childcare professional can have this guide for themselves. I said it gives your intelligence something and then also your intellect, both. So tell us about The Little Iceberg.

DR. ZEEDYK: It all goes back to this question of how do you help people to know this. One of the things I haven’t stressed is that there are no perfect parents. There are no perfect families. You don’t have to get it right all the time. It’s one of the reasons I talk about the power of making up. So it helps people to relax.

So, we’ve got more and more excited on my little team about what kind of resources could we produce that would help people to get this. So we’ve begun to work with other authors and other people who are talking about this wider, wider questions about trauma and relationships with lots of sectors like schools and police and politicians. Okay, how do we do that broadly?

So, the other book we brought out this summer is absolutely The Little Iceberg and it’s written by a head teacher. It’s a story that he wrote for the children in his school. I had done some work with his school, and he began to say I’ve got this story, I wonder how I could get it published and before you know it, I had said my team could publish that for you.

We held a competition and found a children’s book illustrator and this summer we released what was an 18-month project of a metaphoric story of a child who is lonely, traumatize, disconnected, scared. That could be a foster child. It could be a child who’s living in a family who doesn’t feel like they can talk to other members of that family and who’s scared and doesn’t feel connected.

If you just think of children in all the different ways that the might be disconnected. The Little Iceberg is floating a wide open ocean and is scared to be connected, to talk to, to make friends with any of the other creatures in that ocean. And she’s well protected because she’s covered in all that ice, but if she stays with all the ice covering her she will not know the joy of connection.

So the story is the story of a little bird who comes and helps and chips away at that ice. A little bird against a big iceberg, and if that little bird, a friend, a new person, a stable relationship who can stick with it even when the iceberg basically says go away, I didn’t ask for you to land on me. It’s the story of how the ice drops off and she melts and becomes part of the ocean around her.

So the metaphor helps us to get the power of connection and how we can help. So the story itself is full of all sorts of things you can do to help children who feel disconnected, but just to be sure that people were able to pick up on all of those details, we published it with a guide called Making Sense of Trauma which helps you to see the deeper meaning on all those pages.

What we have found is that lots of schools are purchasing that book, some of them for every single classroom in their school, especially now as we come out of COVID lockdown because there are lots of children who will have experienced very uncertain chaotic times in households. We don’t actually know what’s happening for a lot of families during this time, and that book will give a way for teachers to talk with children about what is happening with them, but to do it through a story rather than perhaps talking about their direct experience.

My favorite… we sent the book to have reviews basically from lots of different kinds of people, my favorite review was from a little boy who’s 9-years-old who is named Callum who read the book and said, his favorite bit at the end was when the rainbow comes out because things are bright now for the little iceberg, and that’s not giving away the end of the story. He said because of that, “I rate this book infinity out of infinity.” So, I decided if that’s what a nine-year-old thinks, he’s a really good reviewer.

LISA: That’s very good. Infinity out of infinity. Well, we have so much to catch up on and I am so grateful that our listeners, hopefully you have stuck with us through this marathon interview and talk with Suzanne Zeedyk. Suzanne, tell us where we can go to find some of these resources.

DR. ZEEDYK: They’re all on our website, and that’s the Connected Baby website, so that’s www.connectedbaby.net . So Connected Baby is an organization I founded with my team in order to produce resources. We host events and we stage exhibitions, and in fact we are now working on collecting photographs of reunions after COVID to stage an exhibition called Stories of Reconnection, because reconnection highlights the importance of reunions which was a key message of attachment.

So you can find all of the resources on our website on the resources page and see what else we do. We have a discussion about the science that underpins that, and we are in the process of developing a whole range of resources so if you keep checking back you’re likely to find new things there. We wanted to make this available so it reached well beyond the borders of Scotland, and we have lots of people now from the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, America, Canada who regularly turn up on our site and we welcome everybody, and it’s why it’s really exciting to be talking to you again, Lisa. It kind of feels like a full circle.

LISA: Oh, it is. It’s just remarkable and I can’t believe it’s been 10 years, but okay. We’re here for the long haul anyway. Thank you so, so much. I look forward to having you back to Kindred. And if you are listening to this call you can find a transcript of our call at kindredmedia.org along with some other resources there for ACES and attachment and the new story of childhood, parenthood and the human family. What do you call it Suzanne? The new story of childhood, parenthood, and the human family?

DR. ZEEDYK: I often think of it as the science of human connection, and it begins in babyhood and it carries all the way throughout our lives. There’s even now science that tells us that the symptoms that you exhibit in dementia can be traced back to your attachment style in your first year of life. There is so much for us to know that people don’t know. I think they deserve to.

DR. ZEEDYK: Thank you for having me, Lisa.

LISA: Well, thank you for being here to share with us the science and making it accessible to us.

RESOURCES

Read Kindred’s articles on Adverse Childhood Experiences

Take the Adverse Childhood Experiences Quiz

Kindred’s ACES and Trauma Resources

NEW: Start your own ACES Initiative in America