What Are The Characteristics Of Thriving Adults?

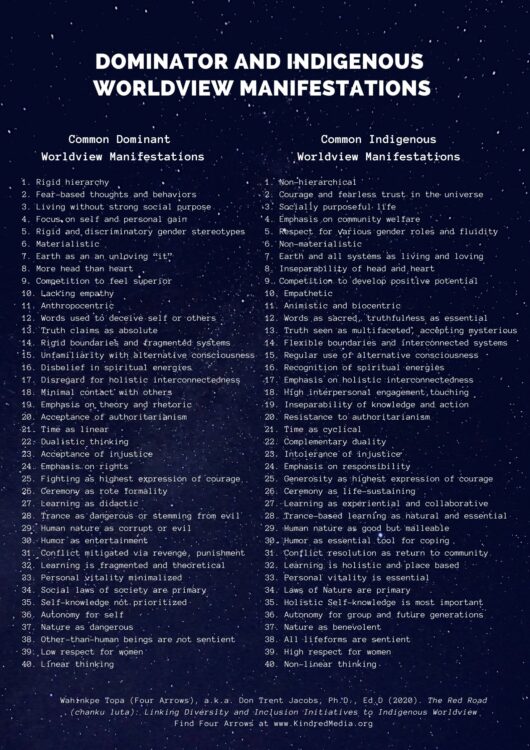

Indigenous Worldview offers a wider view of human potential.

Humanistic and positive psychology have delved into the upside of personality. But Indigenous perspectives are wider and deeper.

How has positive psychology conceived of a thriving individual? Here are three examples.

Corey Keyes (2002) suggested that flourishing combines three types of well-being: emotional (positive emotion and life satisfaction), psychological (e.g., autonomy, self-acceptance, purpose), and social (e.g., social acceptance, integration into the community, actualization, contribution to society).

Martin Seligman (2011) in his book Flourish summarized wellbeing theory using the acronym PERMA to represent the categories he found important for adult flourishing: Positive emotion (e.g., happiness, life satisfaction); Engagement (interest in life); Relationships (people care about me); Meaning (my life is meaningful); Achievement.

Felicia Huppert and Timothy So (2013) studied flourishing among Europeans using items from the European Social Survey. They identified ten characteristics, a combination of feeling and functioning: competence, emotional stability, engagement, meaning, optimism, positive emotion, positive relationships, resilience, self-esteem, and vitality. Individuals’ scores were compared across nations. The top-ranking countries were Denmark, Switzerland, Finland and Norway and the bottom-ranking countries were Russia Federation, Portugal and Bulgaria.

None of these proposals identify how and where they obtained baselines for our species thriving. We know what thriving race horses look like and how to raise them, but social scientists typically have avoided looking for species-normal baselines for human beings (Narvaez & Witherington, 2018).

Maslow is often mentioned as the father of positive psychology with his Farther Reaches of Human Nature and discussion of self-actualization (Kaufman, 2020). It turns out that Maslow’s theory was influenced by the principles for thriving he found among Blackfoot Indians, whom he visited when he was developing his positive human psychology theory (Hoffman, 1996).

Maslow’s intuition about attending to traditional Indigenous peoples provides a good model for us today. Why? Because our ancestors had to survive, thrive and reproduce over generations for natural selection to take place. They had to live in sustainable ways for their descendants to survive. (In contrast, much of humanity today has been living outside of sustainable ways without much concern for descendants.) Many Indigenous peoples around the world continue their ancestral patterns.

Uncovering species-normal baselines for thriving is a transdisciplinary endeavor, integrating evolutionary systems theory and ethology to understand how species grow and thrive, attending to the glimpses and summaries of Indigenous peoples who raise children in our species-normal way (evolved nest) (Narvaez, 2014). Just like other animals thrive when they are raised in their evolved developmental niches, so do humans. For 99% of human genus history, humans lived in nomadic foraging bands that provided humanity’s evolved nest, the developmental system that matches up with the maturational schedule of the child (Gottlieb, 2002). Around the world, nomadic foraging communities not only have similar child raising practices (Hewlett & Lamb, 2005; evolved nest) but similar adult personalities (Ingold, 2005).

Thus, traditional Indigenous peoples, in particular hunter-gatherers, can show us what species-normal flourishing looks like and how it is fostered. Jon Young (2019) gathered a list of adult thriving characteristics from his work around the world and in particular with the Bushmen of southern Africa. Jon Young (2019) also describes the social structures and practices that support individual and group thriving.

I have expanded Young’s list with characteristics that others have experienced across hunter-gatherer groups (e.g., Darwin, 1871; Four Arrows & Narvaez, forthcoming; Ingold, 2005; Sorenson, 1998; Wolff, 2001).

Notice a key difference between what the positive psychologists measure and what Young describes. The psychologists are measuring what people think about themselves (survey of conscious self-perception). Young is describing what a person visibly displays (observation of behavior).

The Thriving Indigenous Individual Exhibits:

- A Quiet Mind. Presence, unbridled creativity based on sensory integration. Attentive. Access to one’s unique genius.

- Inner Happiness. Childlike glee.

- Vitality. Abundance of electricity in the body.

- Being Fully Alive. Awareness of the sacredness of life. A sense of awe, respect, and wonder.

- Autonomy. Follows their own impulses.

- Honesty. Truthfulness is practiced and expected.

- Sense of humor. Focused on human foibles.

- Outstanding memory and senses.

- Builds habits at will.

- Knowhow for getting along in the particular landscape.

- Ecological attachment. Relational respect for nature.

- Connection to Spirit. Has awareness of reality beyond the manifest.

The Thriving Individual-in-Relationship is characterized by:

- Enjoyment being with others. Individuals enhance each other’s pleasure through play, song, jokes, dance, etc.

- Smooth Cooperation. Relationally attuned to subtle communications of others through various senses (e.g., touch). Responsive to the needs of the group. Social fittedness.

- Empathy given and received. Secure connection with others.

- Unconditional Listening. Catches others’ stories.

- Communal orientation. Sense of connection and commitment to the local group and to the Whole.

- Authentic Helpfulness. Personal gifts & vision activated. Commitment to mentoring and “paying it forward.”

- Unconditional Love and Forgiveness.

- Generosity. Sharing is practiced and expected.

- Egalitarian. Each person is their own authority. No one coerces anyone else.

- Respect for ancestors and future generations.

- Responsibility toward the web of life.

All the Indigenous characteristics are marinated in a kincentric worldview that includes other than humans (e.g., animals, plants, waterways, etc.). (See Four Arrows & Narvaez, forthcoming).

When we compare the lists, notice the specifics that are missing in the Indigenous Thriving lists: achievement, self-esteem, optimism, resilience. The Indigenous generally focus on wellbeing and egalitarianism, so there is little focus on personal achievement. Self-esteem is taken for granted as there is no general deficit to overcome since needs have been consistently met from birth (i.e., there is no primal wound or lack of confidence). Optimism typically refers to optimism about the future rather than happiness now, characteristic of settled communities who depend on farming. Nomadic foragers live mostly in the present, deciding what to do each day. Resilience is of course a characteristic of nomadic foragers who live in difficult physical circumstances, but it is not the resilience that is typically measured in industrialized societies where it refers to bouncing back from trauma. (Childhoods in industrialized societies like the USA are full of trauma, and routine violations of the evolved nest in early life, which distresses the baby, changing the trajectory of development; Lanius, Vermetten & Pain, 2010). Indigenous resilience means abilities to survive in the wild (e.g., find food and build shelter).

Notice the kinds of things that are missing in the psychology lists but are in the Indigenous lists: social and ecological intelligences, nature connection, spirituality, a relational web and responsibility towards ancestors and other than humans, sociopolitical attitudes of egalitarianism, individual autonomy, and communalism.

Matching up with the Indigenous list, Gleason & Narvaez (2014) point out that full flourishing among children and adults includes compassionate sociomorality, which relies on a well-functioning neurobiology, what the evolved nest supports. Cooperative sociality is a key adaptation for our species (Hrdy, 2009). Fredrickson and Losada (2005) come close to endorsing this aspect when they say that flourishing among adults means living “within an optimal range of human functioning, one that connotes goodness, generativity, growth, and resilience” (p. 678).

The characteristics of Indigenous thriving offer us a more holistic, detailed, and evolutionarily-grounded picture of species-normal thriving that is relationally- and earth-centered (Four Arrows & Narvaez, forthcoming).

References

Darwin, C. (1871/1981). The descent of man. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Four Arrows, & Narvaez, D. (forthcoming). Indigenous Eloquence and Kincentric Flourishing: Selected Quotes and Worldview Reflections to Rebalance the World. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist, 60, 678-686.

Hoffman, E. (Ed.) (1996). Future Visions: The unpublished papers of Abraham Maslow. New York: Sage.

Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

Ingold, T. (2005). On the social relations of the hunter-gatherer band. In R. B. Lee & R. Daly (Eds.), The Cambridge encyclopedia of hunters and gatherers (pp. 399-410). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kaufman, S.B (2020). Transcend: The new science of self-actualization. New York: TarcherPerigee.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207-222.

Maslow, A. H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. New York: Viking.

Narvaez, D. (2013). The 99%–Development and socialization within an evolutionary context: Growing up to become “A good and useful human being.” In D. Fry (Ed.), War, Peace and Human Nature: The convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views (pp. 643-672). New York: Oxford University Press.

Narvaez, D. (2014). Neurobiology and the development of human morality: Evolution, culture and wisdom. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Narvaez, D., & Witherington, D. (2018). Getting to baselines for human nature, development and wellbeing.. Archives of Scientific Psychology, 6 (1), 205-213. DOI: 10.1037/arc0000053

Seligman, E.P. (2011). Flourish. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sheldon, K.M. (2004). Optimal human being: An integrated multi-level perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Sorenson, E.R. (1998). Preconquest consciousness. In H. Wautischer (Ed.), Tribal epistemologies (pp. 79-115). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Wolff, R. (2001). Original wisdom. Inner Traditions, Rochester Vermont.