Principles of an Indigenous Way of Being, Part 2 of 3

This is part one of a three part series. Please also find Kindred’s resources, including a worldview chart and podcasts, at the end of this post. Click to read the titles below.

Indigenous psychology starts with different premises.

Psychology has thought of itself as culture-free and “objective” or without bias. To understand how far off the mark this is takes an outsider to observe, or humility from the inside. The colonial worldview, introduced briefly in the prior post, was infused in psychology from the beginning.

Arthur Blume (2020) describes key differences between people who identify as Indigenous and those who do not. Blume introduces the Indigenous American psychology paradigm (IAPP).

Principles of the Indigenous American Psychology Paradigm

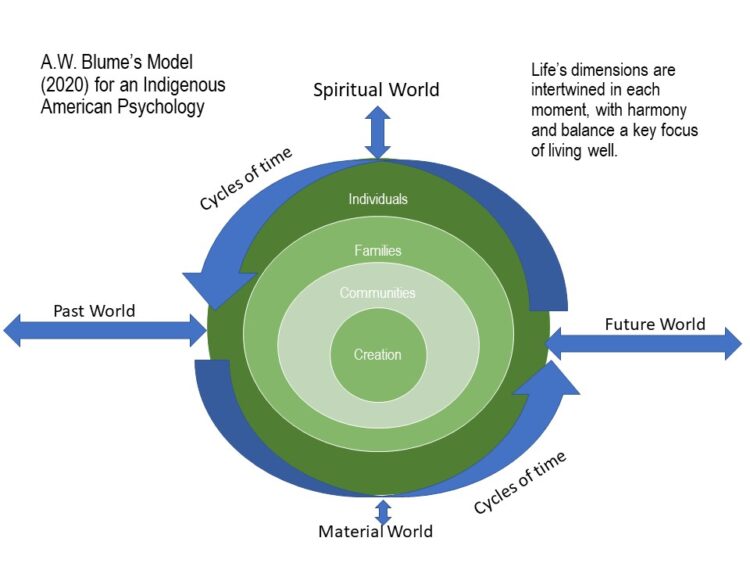

One of the key differences is the central importance of relationship to the Earth. Instead of the individual self at the center, which occurs in Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory, Creation is central, followed by communities, families and then individuals. All are wrapped in the cycles of time, with material and spiritual worlds linked.

Creation’s health and wellbeing are intertwined with the wellbeing of its entities, including humans. When Creation is out of balance, it will have negative consequences on human beings.

The identity of an Indigenous person is grounded in a continual connection with the Earth. Creation is the whole context of existence. This is not only concrete and physical but emotional, psychological and spiritual. An Indigenous person is constantly learning from the Earth—learning how to be a better person in relationship, how to live well, how to enhance Creation. Along with special kinship to ancestral lands, there is a general belief in the Earth as “a giver of life and happiness” (Blume, p. 4). Creation is sacred, meaning “a special and important interconnection of all things, woven together in beauty” and “entitled to reverence and respect” (p. 5). This means that there is a great mystery in Creation, much is beyond human understanding. But everything has an important place, whether we understand it or not. Spirituality means living mindfully, as if in relationship with the whole of Creation, treating all things as sacred, as inherently valuable. Spirituality is about respectful action.

Keeping Creation in balance and harmony is not only a foundational part of the Indigenous worldview but it is considered essential for good health. Life revolves around practices to enhance the awareness of individual and community connection to the Earth.

Treating Creation with respect involves an egalitarian existence. There is no hierarchy in Creation. Humans are not superior or inferior to the rest of Creation. Those attitudes lead to “dumb and preventable mistakes that harm the community and its surrounds” (p. 11). Instead, interdependence of humanity with the rest of the Creation is a basic assumption. Creation is at the center of life, not human beings. Thus, each member is vital for the ‘we’ of the community. Indigenous persons understand that the ‘we’ of creation includes the other than human, humanity’s extended family of sentient beings, a kinship of beings “derived from the Earth” (p. 12). This shared existence is neither lonely nor insecure and instead strong. “Egalitarian partnerships between sacred equals require that the human collective work toward the good of the whole” (p. 11). Each individual’s action reverberates across the whole.

Time is viewed as cyclical. Changing but recurring seasons, phases of the moon, and star patterns are some of the rhythms of life on the planet. Water cycles within ecosystems. Humans, like other life forms, also cycle through life—being born, changing and dying. There is a special reverence for children and for elders because they are close to the spiritual dimensions of cycling in or out of a particular life existence. Ancestors are still understood to be present, but in another dimension or form. The material and spiritual worlds do not have a clear distinction.

Time—past-present-future—is less separable. “Indigenous perspectives see beyond the present expression of things to see the whole picture of how things are related across time” (p. 16). The past and future are wrapped together in the present. This sense of timelessness supports a patient attitude toward the flow of time which will reveal the right time for an activity. More important than getting things done is the process or manner of doing them—with respect and inclusion, avoiding harm to fellow dwellers on the Earth. “Good things will result if we align with the sacredness of Creation” (p. 25).

Keeping harmony and balance is a life goal. Many tribal practices were developed with this orientation. Ceremonies of gratitude remind community members of the processes of proper living. When conflicts occur, various practices were employed to restore balance. Humility, understanding that people are earth (dirt, humus), maintains egalitarian thought and behavior, against hierarchy. “Understanding the consequences of living in an interdependent world promotes a humble approach to living” that is logic and prudent (p. 23).

“Psychological health and well-being are a function of justice and fairness in our relationships with others,” including Creation (p. 88). “Injustice toward the ecosphere is harming all forms of life, including humans, but psychology again has been reticent in challenging the lifestyles that are contributing to the Creation-level injustices” (p. 100). Egalitarianism is required, as is treating all of Creation as sacred. “Respecting the sacred means we treat carefully and deliberately in life, respectful of how our behaviors impact the sacred whole. Our relationships should be filled with a sense and wonder at how amazing others are” (p. 89). Restoring sacredness is a fundamental activity and requires seeing beyond the present moment to the bigger picture. Sacredness resides in interconnectedness. “Without healthy relationships with Creation, you lose touch with what makes you sacred” (p. 90).

Relationships are the location of psychological growth. Kinship extends into the past, with ancestors, and into the future, with forthcoming generations. Restoration of alignment and living respectfully with Creation advances psychological wellbeing. Spirituality is about these right relations, “an activity that challenges dogmatic belief systems that tend to be hierarchical” (p. 96). Humility is a constant companion is overcoming hierarchical tendencies. Anger and fear are considered internal threats, requiring restoration to harmony and balance. Forgiveness is a necessary part of healing.

Blume suggests several ways that aspects of colonial cultures and psychology can be balanced by Indigenous psychology.

- The self can be de-emphasized and social responsibility for the greater good enhanced.

- Individualism and communalism can be integrated.

- Achievement can be redefined as service to the greater good of Creation.

- Individual liberties can be enjoyed in the context of social responsibility.

References

Arthur W. Blume (2020). A new psychology based on community, equality, and care of the earth: An Indigenous American perspective. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.