What is Wellness According to Indigenous Psychology? Part 3 of 3

This is part one of a three part series. Please also find Kindred’s resources, including a worldview chart and podcasts, at the end of this post. Click to read the titles below.

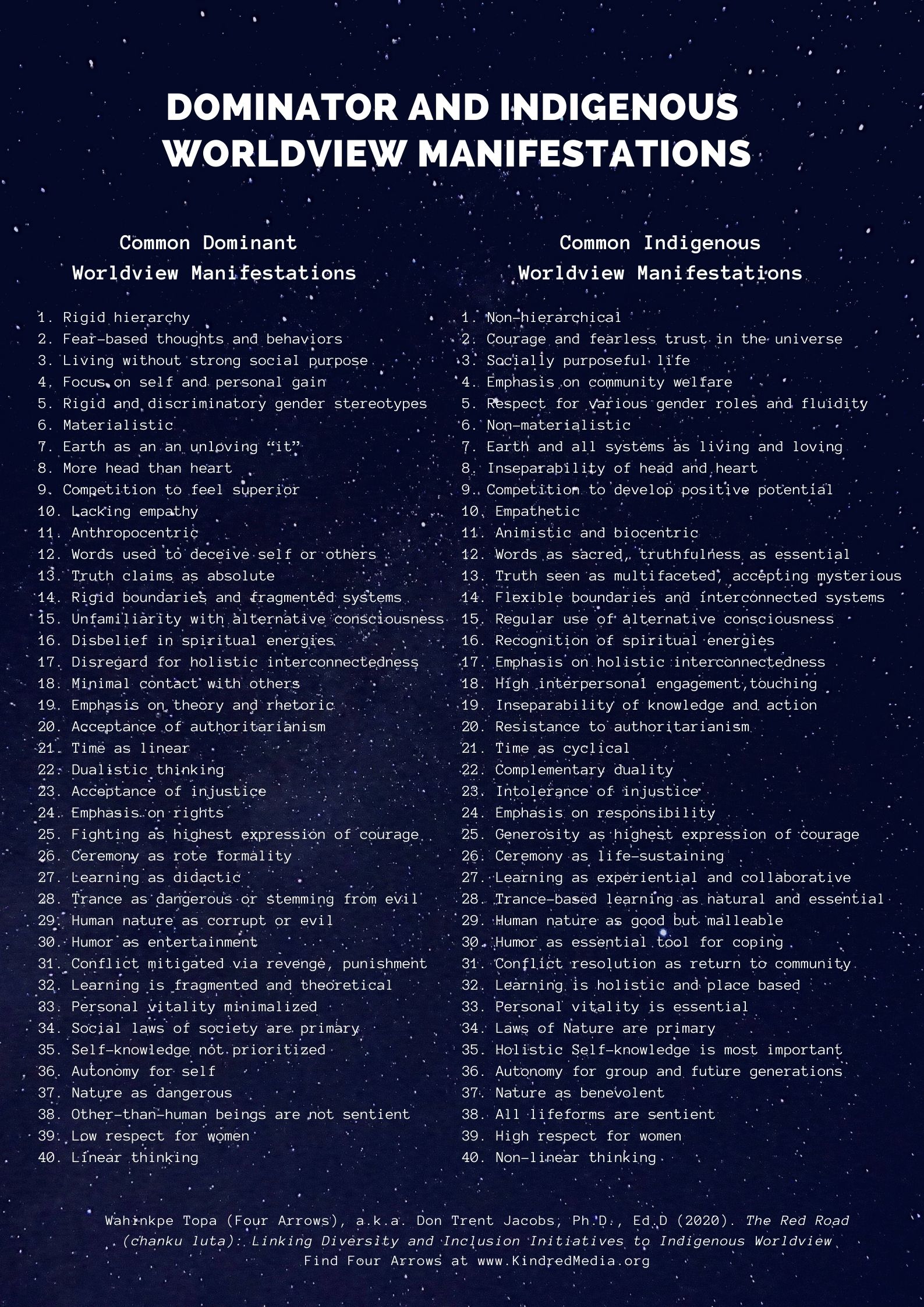

Indigenous psychology contrasts with “colonial” psychology.

Colonial psychology has not done well addressing major sources of psychological distress in hierarchical societies: inequality in education, health, income, wealth; the various forms of discrimination (racism, sexism, etc.). In his new book, A New Psychology Based on Community, Equality, and Care of the Earth, Arthur Blume (2020) suggests that “colonial” psychology has been inept here either because its basic assumptions align with the sources of the problems (e.g., hierarchy) or because it has not embraced diverse voices and perspectives. When voices outside of colonial psychology speak, they are criticized for not being scientific or empirical according to the narrow definitions of what that means. “Colonial psychology remains stuck in a narrow worldview designed to perpetuate itself, consistently confirming biases about the veracity of its homogenous perspective, and unable to grow beyond its limitations” (p. 77). In effect, colonial psychology bandages up the ailments that are largely created under hierarchical relations. See the two prior posts on the content of Blume’s book.

Colonial psychology links wellness to materialism, at least implicitly. Sacrificing material wealth seems like wellness will be risked, that the quality of life will be lost along with personal liberty and independence. Perceptions of personal sacrifice is rooted in fear of “losing.”

In colonial psychology, autonomy is considered a sign of health: of individuation, maturation and identity development; of self-reliance and ego strength. These characteristics allow a person to promote themselves in a competitive, hierarchical society. Dependence is considered a weakness. Although psychology emphasizes self, individualism and autonomy as signals of wellbeing, life sciences do not. The Indigenous perspective aligns with how the planetary ecosystem works—with interdependence. Blume asks, “If the rest of Creation relies upon interdependence for health and well-being, why would human beings be any different?” (p. 67). The emphasis on ego and identity may blind individuals (and the field) to diversity, especially to the non-human.

“There is a thick cloud of smoke covering the social order, suggesting a wildfire of relational psychopathology…a self-oriented, hierarchical perspective cannot put out the wildfire that it has started” (p. 193). “The [Indigenous American psychology paradigm] IAPP views self-orientation as a form of grandiosity since it denies the reality of an interdependent existence and equal partnership with others” (p. 195). Narcissism, covert or overt, is a fragile cover of vulnerability and represents a form of distorted thinking, away from awareness of interdependence. “Self-interest,” whether in an institution, a business or person reflects narcissism.

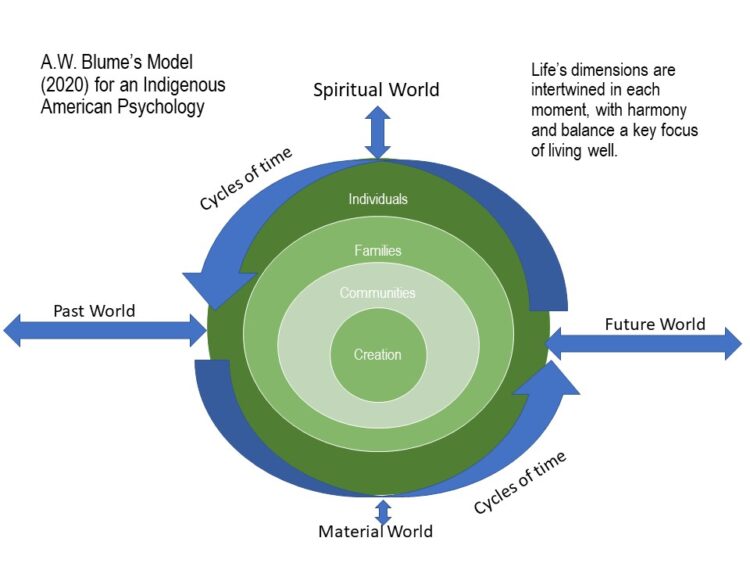

An Indigenous psychology considers wellness to be grounded in spirituality and relationship, not materialism.“Wellness is a function of the quality of our relationships with others” (p. 161). Materialism often becomes a barrier to healthy relationships and in fact imbalances them. Excessive concern about the self, about the past or future makes harmonious relationships difficult. “Disharmony in relationships and personal imbalances are the foundations of psychopathology” (p.163)

Trauma is infused into the social order today, where many basic needs are not met and groups are pitted against one another to compete for basic needs. Perhaps two-thirds of adults have one or more adverse childhood experience, which is linked to worse mental and physical health. Many members of the country exhibit signs of trauma as exhibited by social withdrawal, anxiety, hypervigilance, irritability, fear, shame and anger.

Cruelty indicates relational psychopathology, linked to control or revenge meant to harm or disrespect another member of Creation. Relational psychopathology forms dysfunctional beliefs and actions. Each of us is capable of cruelty when we forget our interdependence and oneness and let our anger and fear become externalized.

IAPP puts wellbeing above self-interest. “A Creation-centric approach is necessary to rein in the frivolous self-interest and temptations to engage in narcissistic and anthropocentric orientations.” (p. 209). Blume encourages liberation from the “material wellness” model (p. 225).

IAPP principles to advance psychological wellbeing, health and happiness include balance and harmony in self and relationships, requiring the mending of relationships with the natural world; moving away from materialism; and linking individual wellbeing to the wellbeing of others. Understanding happiness as a function of relationships would reduce anger and fear. It means psychologists should work with other life sciences about basic needs of the biocommunity and the human use of the natural world.

Instead of subscribing to Descartes’ view, “I think therefore I am,” Indigenous Peoples around the world are more likely to believe “we are therefore we share” (p. 237) (or in Zulu, Ubuntu: “I am because you are”).

Wellness is an ongoing process. Wellness is formed within taking time for relationships, following the cycles and energies of Creation (seasons, solstices, etc.). In the 2019 World Happiness Report (Helliwell et al., 2019), social support significantly predicted greater enjoyment, laughter and happiness and less sadness, anger and worry. Less materialism also predicted the same things.

Healing a person requires addressing the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual aspects simultaneously. It also means healing the social system in which the person resides. Instead of focusing only on the individual, therapy builds up esteem for families and communities. Therapy balances a self-oriented approach with a “we” and “us” framework. “It is helpful to consider the family, community, and Creation as co-clients to the identified client” (p. 129).

Blume contends that overall, colonial psychology needs to diversify. He suggests that several practices be built into the field’s practices. Research findings should be confirmed beyond the colonial society and perspective. Results should show converging evidence across many different cultural perspectives, and with cultures that are very different from the colonial culture. Researchers should demonstrate that their models address divergent worldviews. The research should demonstrate that it advances wellbeing as defined by the worldviews of other cultures, not only the colonial worldview. Only then will psychology embrace the diversity of humanity.

References

Arthur W. Blume (2020). A new psychology based on community, equality, and care of the earth: An Indigenous American perspective. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

John F. Helliwell, Richard Laynard, and Jeffrey D. Sachs (2019). World Happiness Report. https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2019/WHR19.pdf