The Spirit of Manaaki: An Exclusive Book Excerpt

Chapter 7: Whakaora: Restoring Health

We need to heal the ways we think, feel, relate, exchange, and exist. The only possible answer is healing as a collective body.

Maria Jara Qquerar, Quechua Maestra

Chapter 7: Whakaora: Restoring Health

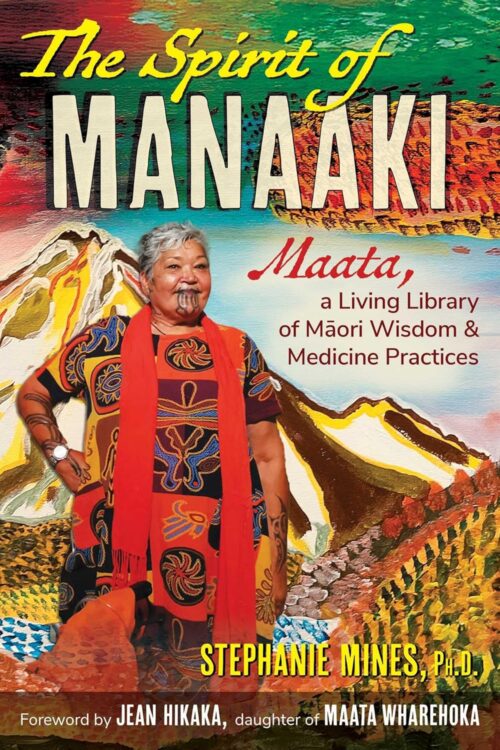

In her watershed treatise on decolonizing medicine, Inflamed, Dr. Rupa Marya and Raj Patel (2021, 24) say, “Practitioners of modern medicine are not trained to be healers. They are trained to be biomedical technicians.” Maata Wharehoka trained herself to be a healer. Her intimate knowledge of the healthcare needs of her people and the ways in which every aspect of their well-being has been attacked by colonialism was evident when she was only fourteen years old and won the distinguished St. John’s Grand Prior’s Award for exemplary service in healthcare. It seemed a direct line to her becoming a public health nurse. Maata modeled culturally sensitive healthcare before that terminology was even used. Holism is innate in her. She has never lost sight of the power of Māori advocating for and shaping Māori healthcare. She has been doing it since she was a teenager!

Dr. Marya, a physician schooled in the United States, continues, “Doctors are trained not only to look exclusively at the patient as a solitary individual—shorn of context or structure, stripped of life in all its complexity—but to treat that individual as a broken machine, as a dysfunctional and occasionally noncompliant robot bearing a symptom.” Rongoā, Māori medicine, is the polar opposite. It embraces the whole person, including their history and their physical environment. Maata’s culturally sensitive, holistic, and nature-attuned approach to healthcare is what the world is desperate for right now. The climate crisis has made this yearning a regular headline.

Healthcare around the world has failed Indigenous people. In truth, it has failed all people, but the insult to Indigenous people is most reprehensible. Just as European settlers in Aotearoa sought to erase traditional Māori medicine, Western medicine throughout the world tends today to disregard, minimize, insult, and ridicule folk and ancient healing wisdom. That is starting to shift as the scientifically sound underpinnings of these resources are acknowledged and integrated into medical practice. The way in which Jean Hikaka and her mother, Maata Wharehoka, were able, in Taranaki, to introduce traditional Māori methods for tying the umbilical cord of the newborn baby is an example of this shift. See the birthing chapter in this book for this healing story.

The New Zealand Ministry of Health (2024, 1) reports that Māori are disproportionately affected by chronic disease, including mental health conditions, and experience a higher burden of anxiety, depression, and mental distress compared to non-Māori. Māori women are twice as likely as non-Māori women to be diagnosed with cervical cancer and 2.5 times more likely to die from the disease. Regular cervical screening can reduce a woman’s risk of developing cancer by 90 percent. Nevertheless, Māori women are reluctant to have screenings in an environment that is unfamiliar and even disrespectful of their lifestyle.

Knowing this, Maata Wharehoka introduced radical changes to healthcare by recommending that screenings could happen on the marae, that easy-going conversation and even food should be included in the screening environment whether in a hospital, at home, on the marae, or elsewhere. As a result of her effective outreach, screening rates increased substantially. In this way, Maata Wharehoka pioneers culturally sensitive healthcare to this very day.

True healing is only possible when it is culturally sensitive. Maata has always known this. She is my mentor in this regard, as I have launched a global program called “Regenerative Health for A Climate Changing World” that is based on reskilling medicine via cultural sensitivity. Maata’s model was Te Puea Herangi’s, who, even though she was not trained to be a nurse as Maata was, was still able to look at Māori health needs and healthcare delivery systems from both Māori and Pākehā perspectives. That is what is necessary for systemic change. How Te Puea acted on behalf of her people during the deadly influenza and smallpox pandemics in the mid-1900s, when Māori communities were underserved, even abandoned, and without resources, remains a model for healthcare today, particularly in regard to compassionate service for Indigenous communities. See the chapter in this book on women’s empowerment, “He Wahine He Taonga: Every Woman Is a Treasure,” for more about Te Puea and her healthcare activism strategies.

Parihaka met the challenge of the COVID pandemic like a strong, regenerative health savvy community, protecting its members and keeping out threats. Maata utilized her skills as a public health nurse in the interest of her community and her whānau. She also used her artistry. Because Parihaka was vulnerable as a tourist site, and because there was a unified commitment to keep infection out, roadblocks and gates were erected to prevent the entry of people who might be carrying COVID. Maata contributed bright and beautiful signs with the clear message to keep out, stay away, stop, do not enter (see plate 7). Everything Maata does is beautiful, even if she is saying, “No way. Stay out!”

Maata knows from her personal experience that art is healing. Her paintings, weavings, and poetry in this book demonstrate how art lifts her up, allows her to voice her truth, and is an outlet for her passionate love and dedication. When Rose Pere instructed Maata to “heal Papatūānuku,” she was speaking of healthcare at its source. Maata knows, and frequently declares, that everything she does is designed for healing. She fulfills the true definition of what it means to implement healthcare.

The Root Structure of Health:

Te Ao Māori Meets Attachment Theory

I have lived most of my life with the certainty that I was poorly attached. How could it be otherwise, I wondered, particularly after I became a neuropsychologist. In the literature I read by every highly respected author, from Winnicott to Mate, from Mahler to Schore, it was unquestionable that, given the violence in my home, given the sexual abuse and dysfunction of my family, I had to be poorly attached. That was certainly what was wrong with me. This was why I struggled with relationships. This was why I had so much difficulty with confidence. The grief of how I was so marked by my family’s dysfunction was endless. It was a bottomless well.

It is only recently that I pierced the lie of this assumption and its colonial, patriarchal underpinnings. It has become crystal clear to me that, in fact, the opposite is true. I am amazingly, brilliantly attached and bonded to what really matters—which is the natural world, creativity, and my lineage. Not only that, but I am incredibly resilient in adapting that attachment, those bonds and connections, to a variety of ecosystems and communities. It is not case dependent. It is within me and inseparable from me. Indeed, I have been powerfully and securely attached from the moment I took form. This is a matriversal understanding. It comes from the standpoint of being akin to the natural world. It is also the perspective of an embryologist who understands human development from the beginning of life.

It is only recently that I pierced the lie of this assumption and its colonial, patriarchal underpinnings. It has become crystal clear to me that, in fact, the opposite is true. I am amazingly, brilliantly attached and bonded to what really matters—which is the natural world, creativity, and my lineage. Not only that, but I am incredibly resilient in adapting that attachment, those bonds and connections, to a variety of ecosystems and communities. It is not case dependent. It is within me and inseparable from me. Indeed, I have been powerfully and securely attached from the moment I took form. This is a matriversal understanding. It comes from the standpoint of being akin to the natural world. It is also the perspective of an embryologist who understands human development from the beginning of life.

I attribute this awakening, in part, to my time in Aotearoa with people like Rangatira Maata Wharehoka and her family. They did not impart the awareness directly. It grew as a by-product of my time with them and my capacity to track what was being aroused in me as a result of being in that environment and with the Māori people.

The Indigenous worldview that Maata and her family embody communicated itself in daily actions, not in lectures, discourse, or books. This is matriversal education. As I harvested flax with them for weaving, ate with them, laughed and cried with them, something that had always been with me surfaced from where it was buried under the misogynistic, elitist psychology required for mental health professionals. The ease with which Kuia (Elder) Maata could shed what was untrue reminded me of what was natural to me, but what I had been taught to be ashamed of or suppress. She inspired me to prioritize my own experience over the dictates of academia, which is, for the most part, disembodied. Maata had no need to pamper or indulge anything untrue.

What surfaced as a result of this communion with Maata and others at the epic Parihaka marae in Taranaki, was me, the real me, the one who had always been deeply connected to everything and everyone. It is actually because of my deeply connected, compassionate awareness that I am able to develop my creativity and my intelligence, even when my ideas are not necessarily popular, and even if they are ridiculed. Nothing stops Maata from voicing her truth because her sense of herself is too deeply rooted. She knows that her tūpuna (ancestors) have her back. She mirrored this for me, and the reflection stuck.

I had previously been convinced that I was an outcast, an oddity, but this, I discovered, was imposed upon me. It did not arise from within me. It had never been true. That became clear to me at Parihaka, in the company of Maata Wharehoka. I cannot overemphasize the magnitude of the about-face that comes with the somatic realization of belonging. I was never outcast. No one is. I am welcomed in by the universe, celebrated, desired, and loved. The cell-deep certainty of this changed everything.

I have always been deeply bonded with the spirit world, though I had no language for claiming that before. In Maata’s environment, the spirit world sits down for kai (food) along with everyone else. It was that unerasable, sustaining bond that was a natural part of everyday, practical activity that came home to me. I saw that I had always had this bond and that it had allowed me to transcend the cruelty and chaos of a family home riddled with unresolved trauma. Maata and her family have worked hard to reclaim their language and their tikanga (practices), often adapting them to current conditions, with great success, like Kahu Whakatere, the practices for death, dying and burial. This is a teaching for the world.