The Essential Worldview Reflection Approach to Re-Balancing Life Systems On Earth

An essay inspired by the introduction to the new book by Four Arrows and Darcia Narvaez, Restoring Our Kinship Worldview: Indigenous Voices Introduce 28 Precepts For Rebalancing Life On Planet Earth.

We propose that to rebalance life systems on earth we must contrast and seek complementarity between the dominant worldview that has guided humanity towards extinction, and the Indigenous worldview that has proven sustainable. “Worldview is a concept ‘whose time has come,’ and its increasing appearance in the contemporary climate change and global sustainability debates can be understood as both response to, and reflection of, the challenges of our time and the solutions they demand.” [1] Everyone acts according to their worldview, an implicit set of assumptions that guide behavior.

Among scholars, the term Weltanschauung was first used, and only once, by German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) to refer to sense perception of the world. The term spread through German scholarship. It evolved to mean an intellectual and intuitive concept of the universe. Mark E. Koltko-Rivera’s seminal integrative work on the psychology of worldviews referred to the concept as vital for cognition and behavior and noted how it has been underused. He described the Indigenous worldview of cultures around the world as seeing “subjectivity inherent in the natural world itself ” with all that is, and he contrasted it with the Western world, which sees in a segmented way. He wrote: “In summary, the scholarly study of mysticism defines at least three dimensions of worldview: beliefs regarding the underlying unity of reality, the existence of a conscious nature, and the possibility of a truly ego-transcendent consciousness. Implicit in the mystical approach to the world is the notion that it makes a difference as to whether one sees the world in materialist terms or in terms that allow for an ontologically real spiritual dimension to reality.”[2]

We go further than Koltko-Rivera and assert that the worldview that considers Nature as intelligent and living and the worldview that perceives Nature otherwise are the only two essential worldviews. As we discuss below, it is difficult to find a third category. This may be illustrated by the mystical experience of Edgar Mitchell, one of the Apollo 14 astronauts and the sixth man to walk on the moon. He founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences to explore the relationship between worldview and the suffering that civilization has caused on the Earth. Looking back at planet Earth from outer space made him realize that the “great frontier wasn’t the exploration of outer space, but a deep and systematic inquiry into the nature of our inner awareness.” [1] After witnessing the research of his institute, he would late write that “Only a handful of visionaries have recognized that Indigenous wisdom can aid the transition to a sustainable world.” [2]

The Indigenous worldview as we describe it is not a matter of perception or conception alone, but of experiencing and being. It is more of a “world-sense”[3] because it involves dozens of senses.[4] Indigenous Peoples have a broad integrative understanding of body, mind, and Spirit that allows for a more holistic orientation than the narrow perspective that has led us toward extinction. We two authors have searched for a better word to describe the proverbial invisible waters in which we swim that are the foundation for our assumptions and actions. Robert Wolff called it “original wisdom.”[5] Because of its wide, cross-sensory scope, Indigenous worldview in its fullest sense, is more of an existencescape, Steve Langdon’s term for describing the Tlingit people’s way of being.[6] Langdon explains that reciprocal sensations, not seeing, are how Tlingit understand humanity’s place in the universe. Indeed, tribal knowledge worldwide stems from language birthed in its speakers’ wilderness environment, cultivated through interactions with local spiritual entities, and passed on through thousands of sacred stories and ceremonies grounded in resident relationships. Existencescape prioritizes this place-based knowledge, knowledge that varies according to the interaction between a particular landscape and the People who live there. In this book, however, we wish to emphasize the common precepts shared by Indigenous Peoples across the global landscape. As vital as place-based knowledge is, this book is designed to help those with a Eurocentric mindset to begin the journey toward a kincentric relationship with the Earth, starting with the larger worldview diverse Indigenous cultures share. Dennis Martinez, who identifies as O’odham, Chicano, and Anglo, coined kincentric as a way to include all aspects of “harmony between people and other people, and between communities and people and the natural world.” [1] Kincentrism is the first step towards returning to an earth-based consciousness, a starting place for re-localizing or restoring place-based knowledge.

With all this in mind, we have selected speeches and writings from Indigenous leaders that reflect Indigenous worldview precepts rooted in the ancestral human nature and collective unconscious we share. The precepts represent different dimensions of life. Some precepts are principles put into practice on a daily basis. Some are assumptions about how the world works based on generations of observation. All are guidelines for behavior and living a good life. We consider the precepts to be an essential starting place for bringing balance back into the world.

We use our unique scholarship specialties to analyze and explain our perspectives on the Indigenous quotes via brief dialogue. Darcia’s work encompasses evolutionary moral developmental psychology. She studies how humans develop best within our evolved continuum of child raising, patterning the individual’s psyche, relationships to human and other than humans, including the world of Spirit. Four Arrows has been a proponent of the original Indigenous worldview and its incorporation into education. The result of our collaboration is a deeper understanding of what it means to be a human being, a member of the earth community, in ways that contrast with the anthropocentric/materialistic dominant worldview. Throughout the book the two of us bring forth insights from our experiences and scholarship in an effort to help readers learn and apply the precepts to their own lives.

We believe that original Indigenous understanding of the world offers the most crucial way to rebalance life systems. This is not a romanticized notion. It is ancestral wisdom. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services’ 2019 report provides concrete evidence. [1] The report had data contributions from hundreds of scientists from 50 countries and is the largest ecological analysis ever undertaken. Although we believe it may be too late to stop many of the impending extinctions of life on earth, this is all the more reason to heed the words spoken by our selected guests. They show us how to live with the fullness of appreciating the wonder of the gift of life on Mother Earth no matter how great the challenges. For those who want to help others adjust to whatever lies ahead, our book provides an opportunity to re-embrace our original Indigenous worldview. Whether or not the Indigenous spirit somehow returns to Earth, we hope it will strengthen you in your personal journey while doing what you can for future generations.

We are not alone in our identifying only two worldviews. Robert Redfield, considered to be the “father of social anthropology,” introduced this hypothesis while at the University of Chicago in the 1950s.[2] Redfield considered the replacement of the Indigenous worldview by dominant worldview as one of the great tragedies of human history, seeing the replacement of the moral order of pre-civilized societies with the technical order of modern civilization. From his fieldwork and academic research, he asserted that the “primitive” cultures he studied seemed to have an automatic or natural morality that emphasized empathy and compassion for All. From this perspective, “Industrialized humans have become unvirtuous and holistically destructive in comparison to 99% of human genus existence…The pillars of original virtue include relational attunement, communal imagination, and respectful partnership with the natural world.” [3] We think you will see such morality in the words we offer in the following chapters.

To shift from the dominant worldview to the original Indigenous worldview takes some “decolonizing” of the mind. Our minds have been suckled on the milk of civilization’s domination and coercion of life with industrialization and capitalism increasing disconnection and alienation from earth consciousness. This book is planting the seeds for decolonizing your mind. Please take further steps in this direction by investigating the speakers and materials we cite.

One concern or question that often comes up with our recommendation to decolonize and Indigenize our minds and institutions relates to the right of “non-Indian” people to attempt to re-Indigenize themselves and their systems such as education. Indeed, many Indigenous people believe that non-Indigenous teachers have no right to try and “teach” the Indigenous worldview. They call it a cultural appropriation. Such a concern is well-grounded and must be respected in light of the massive mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples in the last half millennium. However, many Indigenous elders believe otherwise. They know about misappropriation, but they also know that with sincerity, respect and support for Indigenous rights, allies are necessary. An increasing number of leaders are sharing Indigenous wisdom in order to restore harmony and balance.[1] And as others note too, “the aim is not to return to the details of Native ways, but to apply Indigenous values appropriately for our time and with an eye to the future.”[2] The Indigenous Worldview reflects the original instructions for how to approach living well on the earth. As Manitonquat (Medicine Story; Wampanoag) noted: “The Original Instructions are not ideas. They are reality. They are actually Natural Law, The Way Things Are—the operational manual for a working Creation.”[3]

One of the most respected of the Oglala Lakota Spiritual leaders was Frank Fools Crow. Passing away at age 99 in 1989, many considered him the most revered holy person since 1900. He spoke about certain good spirits as a gift to the whole of humankind. He talked about how he helped individuals with Vision Quests and the Sweat Lodge so they might better understand themselves and find peace. Then he added, “And these ceremonies do not belong to Indians alone. They can be done by all who have the right attitude, and who are honest and sincere about their belief in Grandfather and in following his rules…Grandfather’s spirits serve others as well as the Indian.”[4] Fools Crow knew that survival of the world depends upon our working together and sharing what we have. He continued, “The ones who complain and talk the most about

giving away medicine secrets are always those who know the least. If we don’t share our wisdom, the whole world will die. First the planet, and next the people.”

We realize that many readers may feel it inappropriate to “re-Indigenize,” that they me be “misappropriating Indigeneity.” We honor this concern but reserve it many other applications. If you are doing everything you can to help the existing First Nations achieve sovereignty, save their languages, teach us the old ways, this protecting both place-based traditional knowledge and worldview. However, the Indigenous worldview belongs to all of us and there are not enough Indigenous peoples who still are able to practice our original Kinship worldview. We are all indigenous to this planet and we are all suffering.

Discussion Questions and Resources

What’s a worldview?

A worldview is a delocalized general sense of how the world works. It’s a cosmology about what humans are, what they should learn, how they should behave and their purpose; how humans relate to the rest of the manifest natural world; and what is our relation to the unmanifest, the spiritual?

Worldview and TEK

Worldview differs from traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that is localized knowledge Indigenous/First Nation Peoples develops from deep experience in a particular landscape.

So, there are two kinds of Indigenous knowhow missing in the dominant culture that are apparent around the world in First Nation Peoples: the Kinship worldview and TEK. Our book focuses on the former.

How did we lose the Kinship worldview?

Our baselines for normality shifted over time in terms of child raising and cultural practices, downshifting human nature to primate levels. Allowing unfettered inequality has led to endemic Wetiko virus (cannibalistic greed). Modern societies operate trauma-inducing pathways instead of the wellness-promoting pathway we evolved.

How does the Kinship worldview differ from the dominant one?

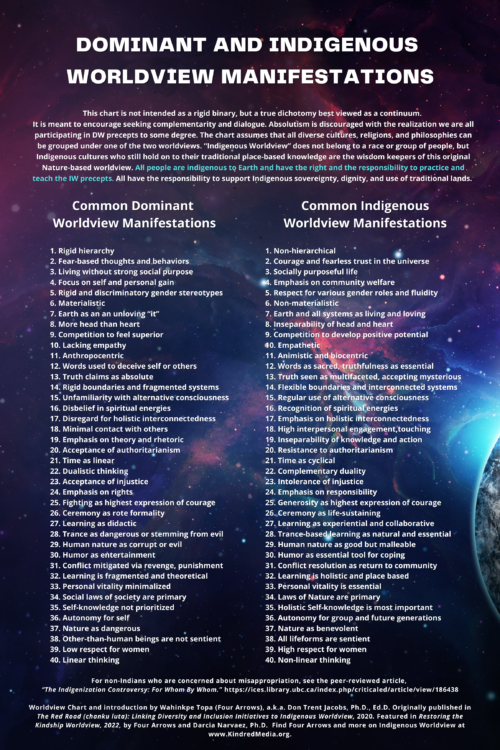

See the Worldview Chart. Worldview” does not belong to a race or group of people, but Indigenous cultures who still hold on to their traditional place-based knowledge are the wisdom keepers of this original Nature-based worldview. All people are indigenous to Earth and have the right and the responsibility to practice and teach the IW precepts. All have the responsibility to support Indigenous sovereignty, dignity, and use of traditional lands.

“For non-Indians who are concerned about misappropriation, see the peer reviewed article,“The Indigenization Controversy: For Whom By Whom.”

The Worldview Chart and introduction was created by Wahinkpe Topa (Four Arrows), a.k.a. Don Trent Jacobs, Ph.D., Ed.D. and originally published in The Red Road (chanku luta): Linking Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives to Indigenous Worldview, 2020. The chart is featured in Restoring the Kindship Worldview, 2022, by Four Arrows and Darcia Narvaez, Ph.D.

Download your Worldview Chart poster or graphic below:

Kindred Worldview Chart Starry Night Background in PDF format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart Starry Night Background in PNG format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart in black and white for printing in PDF format: Download

Kindred Worldview Chart in black and white for printing in PNG format: Download

I absolutely love this article…being robbed as a 6 yr old child from my homeland of so-called present day Colombia and sold onto the international market to a Euro-American family here in Connecticut I have still surpringly retained my indigenous worldview despite all my colonial upbringing. I started to little by little unpack my ideas and do real soul searching until I realized I’m nothing like the people who raised me nor surprisingly my birth family in Colombia who are extremely colonized especially with their religion and see me as backwards and don’t accept myself or my daughter either. It’s been a long arduous road to self-acceptance finally now in my 40’s especially living in a predominantly very white colonial area of Connecticut. I have for as long as I can remember having a unique way of Being that is like a prism and can see all sides and find myself in a myriad of dimensions all simontously! But first and foremost I see the Spiritual way before hand and that is the level I most love working on at all times to comprehend all of Life!