You, your children, your family are invited to discover ways to connect with nature, renew your ecological attachment, and restore your living connection to the Earth.

Dr. Darcia Narvaez and her students did an experiment to increase ecological attachment—nature connection—through small daily practices. Each day participants practiced one activity that increased attention to and being grateful for the natural world. See here for the press release about the study, published in EcoPsychology.

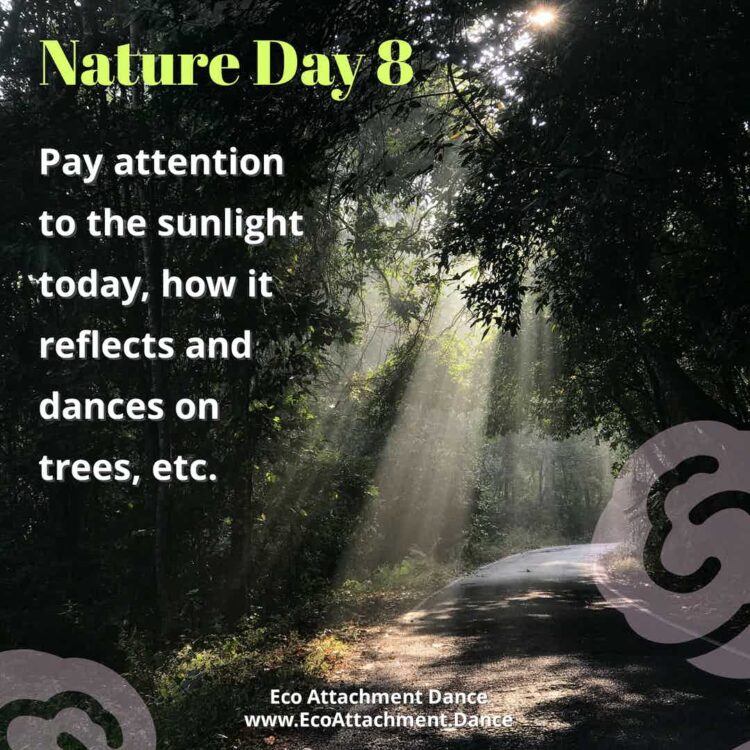

Take up the Eco Attachment Dance to expand your own ecological attachment. Each day for 28 days you can use the Eco Attachment cards to practice that day. Each activity takes about 5 minutes (though you can go longer).

If you would like to take the anonymous pretest (and later a posttest) you can see how your attitudes and behaviors change after participating in the Eco Attachment Dance.

Click here to start the dance on Instagram.

Or see the entire 28 day challenge prompts here.

About the Study

Taking time to commune with nature increases feelings of connection to it, study shows

In designing a recent study, Notre Dame Professor of Psychology Darcia Narvaez wanted to test the possibility of promoting the sense of ecological attachment that was inherently part of many pre-industrialized societies and is still practiced by First Nation peoples. An experiment that was part of the study, now published in Ecopsychology, showed that students reported increased mindfulness towards the environment after performing ecological attachment tasks like contemplating nature, or practicing environmental preservation tasks like recycling and limiting electricity usage. Only the tasks that had students communing with nature increased feelings of connection to it.

“Thomas Aquinas famously suggested two routes to faith and divine inspiration: the good book and the natural world. In a time when Mass attendance and parish events are curtailed by the pandemic, it may be a good time to restore the second route to God, the natural world,” said Narvaez. “Many non-civilized societies used this route, treating natural entities as fellow community members — First Nation peoples notably so.”

Narvaez, along with former graduate student Angela Kurth, now at the University of St. Thomas, and undergraduates Reilly Kohn and Andrea Bae, conducted a three-week experiment comparing two conditions: The first emphasized conservation behaviors such as turning off the lights when you leave a room; the second condition emphasized ecological attachment, which includes things like acknowledging trees and sitting in nature while deliberately listening to sounds.

The team randomly assigned undergraduate participants to one of the conditions. After taking a pretest survey in the laboratory, participants read motivating information about their condition including scientific facts, an essay and a poem. Next, participants were given a set of possible actions to take in the following three weeks. They selected 21 actions that they put into an envelope to choose from, a different one for each day. At the end of the three-week period, participants took a post-experiment survey.

The students in the conservation condition increased in what was called “green action,” or doing things to preserve the environment like recycling and reducing use of disposables. The ecological attachment group increased in ecological empathy, or concern for non-human entities. Both groups increased their ecological mindfulness, keeping in mind the well-being of the environment and all it contains when going about daily routines.

Students enrolled in Narvaez’s Morality, Parenting and Nature Connection course this past spring semester completed similar activities and reported positive results.

“Before this class, I think I tended to believe that humanity was somehow above other animals and separated from the natural world, but I have since been shown again and again just how mistaken I was,” said Claire Rudden, a 2020 graduate.

Isabel Botero, a 2020 graduate from Colombia, was unable to leave her home during quarantine lockdown in her city but made communing with nature a priority as part of course assignments. “It challenged me to adapt those outdoor activities to things that I could do while on lockdown in an apartment. I watched birds through live cams, and I grew a bean — something I had not done since kindergarten, but really enjoyed. It was a way for me to become a kid again and to distract myself from the situation my country and the world is currently living through.”

While ecological destruction runs apace in dominant countries and cultures of the world, an increasing number of Westerners, including scientists, are noting the sustainable lifestyles among indigenous communities who traditionally care for the well-being of their landscapes. The data show that land areas controlled by First Nation peoples around the world have more biodiversity. First Nation peoples control about 20 percent of the lands that hold about 80 percent of the biodiversity. Even the recent report by the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services suggested that indigenous ways of living on the Earth should be integrated in actions moving forward. “Increasing ecological attachment may be necessary to shift individuals and societies away from ecologically destructive actions,” Narvaez said.

Narvaez and her team demonstrate that it is possible to develop the ecological attachment that sustainable native communities display. The daily actions used in the study can be adopted by most people — even at home — and are detailed in the paper.