Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what people will submit to, and you have found the exact amount of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them; and these will continue until they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.

– Frederick Douglass

in a letter to an abolitionist associate, 1848

About Nursing Narratives

Our first narrative of who we are is shaped by the evolutionary act of breastfeeding. Eye-gazing, skin-to-skin holding, touch, nourishing milk that changes its composition with our needs, wire our neurobiolgy for peace by reassuring us we are welcome and safe. It’s impossible to miss the connection between our lack of early bonding through breastfeeding and our confusion and denial over who we are as a human family. In her research on our Evolved Nest, Darcia Narvaez points out we are far from our evolutionary design as peaceful, cooperative species, and are now an atypical species degrading our environment on a path of extinction. We don’t remember who we are, and we’re not listening to each other.

Not listening, making excuses to not listen, dedication to perfectionism, busyness, and more turn out to be well-defined characteristics of white supremacy culture, which are also aspects of toxic masculinity, patriarchy, colonialism, malignant narcissism and Dominator Culture. Nonprofit organizations, with 83 percent white leadership, and the top 315 American nonprofits at 90 percent, are noted in social science research to be bastions of white supremacy. (See characteristics of white supremacy in nonprofit culture.)

In the Nonprofit Quarterly’s How White People Conquered the Nonprofit Industry, Anastasia Reesa Tomkin writes: “White leaders, all 83 percent of them as the statistic goes, are still refusing to defer to the leadership of people of color, even when their clients are predominantly people of color. Some might compare white nonprofit CEOs to slave masters who considered themselves ‘good,’ only looking after the best interests of the plantation by overseeing labor and resources.”

The reflective tale below recounts my experience last June at the United States Breastfeeding Committee’s 2019 Ninth Annual National Breastfeeding Conference and Convening, where I witnessed the intentional, ongoing transformation of a mostly white professional, national nonprofit toward an equitable, diverse, and inclusive powerhouse. It here that I met the Wisdom Council members of Reaching Our Brothers Everywhere, ROBE, who were featured in Kindred’s Father’s Day 2020 series, Meet the Men of ROBE: Standing at the Intersection of Breastfeeding, Infant Mortality and Social Justice.

The series also features an interview with Kimarie Bugg, DNP, who, as the founder of Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere, ROSE, helped to both create ROBE – and guide the USBC’s often intense and emotional process.

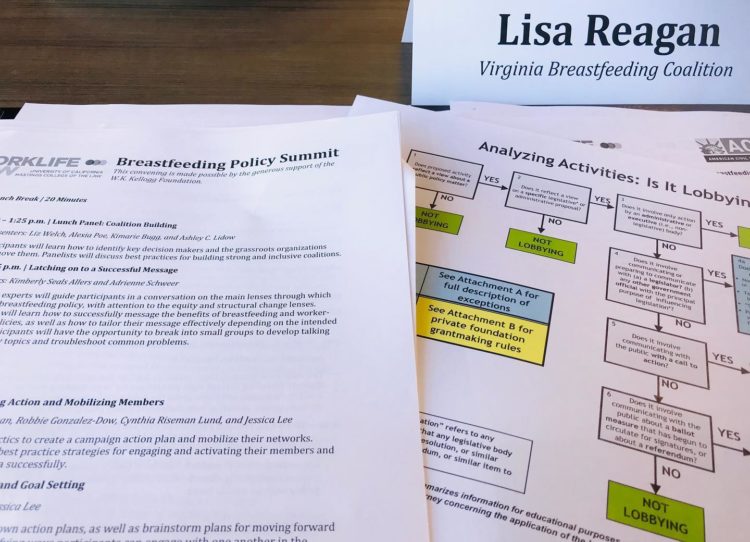

The feature also shares my experience in August 2019 at the Center for Worklife Law’s Breastfeeding Policy Summit, an Advanced Activists Only event, in my view, where we were educated in “playing the game” of systemic change through lobbying as nonprofits, speaking the language of partisan politicians. Through the social science research over 25 years, we learned the real barriers to workplace breastfeeding support: class cluelessness and toxic masculinity.

This tale of my visits to bi-coastal breastfeeding conferences last summer shares how deep listening, safe, brave spaces, and radical truth-telling make systemic change possible, maybe even inevitable.

“In my dream, my breastfeeding dream, I see rivers of breastmilk flowing down the streets of these distressed communities. Healing, bonding, nursing and making whole what was dissected and dismembered. My vision for men is that they benefit from supporting and protecting the breastfeeding experience in ways that help them to reclaim their humanity. My vision for ROBE, is that neighborhoods, communities, cities across this country take advantage of and benefit from this assemblage, this collection, in ways that matter to those communities.”

CALVIN WILLIAMS, ROBE WISDOM COUNCIL

Nursing Narrative Sections

Transforming White Power Structures Through Deep-Listening, Safe Spaces and Radical Truth-telling

Class Cluelessness, Corporate Goddesses, and White Supremacy Barriers to Breastfeeding

Transforming White Power Structures Through Deep-Listening, Safe Spaces and Radical Truth-telling

The first African-American woman elected to the USBC board of directors, Bugg shared with Kindred, “There was a lot of crying and stomping and walking out of the room, and hugging, and more crying. Lots of that. There were times where folks truly wanted to walk out. There were times where feelings were hurt and toes were stepped on. It was difficult for, you know, the oppressor never wants to release power, and especially when you have no idea that you’re holding the power. It’s the white privilege… Until you understand or are presented with the realities, then you’re not really expected to be willing to make these changes. Some people, after addressing these concerns, were not able to make these changes, but a majority of the folks were. That’s why it took several years, but they have truly made a phenomenal transition.” (Listen to the interview and read the full transcript here.)

– Kimarie Bugg, DNP, Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere

One year ago, in a rare non-celestial event, I abandoned my chronically inflamed earth body’s orbital balance between bed-desk-garden-kitchen and cautiously drove three hours towards Bethesda, Maryland, and an international convening of breastfeeding professionals, academics and cultural change makers. Most of the careful planning for the three-day event was internal, with Krishnamurti’s perspective on illness as “just another state of consciousness” guiding my intentions to acknowledge and release any sabotaging narratives my brain offered, while reassuring my body I was listening, and all needs would be met.

“You don’t look sick,” is a normal response to autoimmune-challenged people, which is why many of us don’t talk openly about our illnesses, but we do talk with each other. The AI strategy for navigating a break from safety begins with deep listening. Inattention, not listening, left unheard needs of living tissues whimpering towards eruptions, breakdowns, and rage. Simple attention and patient curiosity are often the cooling balm needed. AI’s ongoing lesson, and one I took my time accepting: any physical, mental or spiritual ambition begins and ends with the living needs of the body. These mindful meditation and deep listening practices also serve my ongoing inner work to understand my own enculturated racism, as I discovered last summer. (See Rhonda Magee’s The Inner Work of Racial Justice: Healing Ourselves and Transforming Our Communities through Mindfulness.)

The first United States Breastfeeding Committee conference I attended in 2014 explored “Transforming Barriers into Bridges: Cultivate Your Community Leadership.” The USBC website states 2014 was the first year the conference focused on “developing capacity and commitment to achieving racial equity in breastfeeding support.” The USBC, a nonprofit coalition of over 100 organizations, signaled in this statement they were at the beginning of an organizational deep listening process. By 2019, the USBC’s Ninth National Breastfeeding Conference and Convention demonstrated – often intensely and unnervingly – an internal sea change with immeasurable, potential impact, a culturally epic phenomenon worth abandoning my preferred hermetic life to witness.

The first day of 2019’s academic presentations withered my spirit. In my hotel room I studied the labyrinth in the shape of a brain ten stories below my window and wondered if I’d made a mistake. By the second day, the energy in the ballroom accelerated, subtle at first, with ongoing finger-clicking responses and emphatic vocal agreements echoing around the room as presenters revealed structural and institutional racism, sexism, and gender-inequality as insidious and pervasive barriers to infant and mother wellness.

“This isn’t the same conference,” I whispered in the hotel’s lobby to Laurel Wilson, a USBC board member at the time and a Kindred International Editorial Advisory Board member.

“And this is on purpose,” she smiled and replied cryptically. I promised to follow up with her after the conference and wondered to myself on the way back to my seat how such an organizational shift could be purposefully engineered.

Raw emotion coupled with stark truth-telling, not features of the USBC’s mostly white privileged professionals’ conferences of the past, continued into break-out sessions. In a Mid-Atlantic Regional circle, where I sat with my Virginia representatives, Lourdes Santaballa, a lactation consultant from Puerto Rico, quipped with the certainty of an oracle, “You think we’re unique in Puerto Rico, we’re not. Everyone needs to get ready.” (In October 2017, following Hurricanes Irma and Maria, Lourdes founded Alimentación Segura Infantil, an Infant and Young Child feeding program focused on increasing breastfeeding, leadership and training in marginalized communities in Puerto Rico.)

Whatever intentional changes the USBC board began over the past four years, the result appeared to be a living container for the expression of unmet human needs. The experience felt intimidating at times with its managed anger, but alive in its honesty. A few conference attendees, waiting for their turn at open mikes, simply declared their fury at “white, straight men.” As the wife and mother of white, straight men, I had to sit with that one.

Clues of evolution in action were ubiquitous. A small note in the conference program stated, “USBC welcomes and values all types of knowledge, including academic, lived experience, communal, and beyond.”

“And beyond…” There was room for more growth, insight, and embracing of living energies still to come.

Instead of intellectually distant and self-congratulatory white power structures dictating a clinically-detached agenda, the living intelligence of human needs, and the meeting of those needs, appeared to be welcome and heard. In a few, short years, the USBC’s Annual National Breastfeeding Conference and Convening began a transformation of itself from a mostly white, professional, female event, to a vastly more inclusive, diverse, alive, steely-eyed, activist-driven, international gathering.

It would be eight months before former USBC board member, Kimarie Bugg, DNP, would share with me the inside story of USBC’s revolutionary change, initiated by Bugg and her nonprofit, Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere, ROSE, with “a lot of crying and stomping.”

The first African-American woman elected to the USBC board of directors, Bugg shared with Kindred, “There was a lot of crying and stomping and walking out of the room, and hugging, and more crying. Lots of that. There were times where folks truly wanted to walk out. There were times where feelings were hurt and toes were stepped on. It was difficult for, you know, the oppressor never wants to release power, and especially when you have no idea that you’re holding the power. It’s the white privilege.

“So, we had to have those conversations, and when you know better you do better. I talk a lot in my little presentations about Johari’s Window. I know what I know, I know a little bit about what I don’t know, and I know nothing about what I don’t know. So, if something has always been this normalized and you do not see in your base anything about slavery and Jim Crow and redlining and about toxic dumps being put in neighborhoods and then segregation and all of those types of things.

“If you’ve never had any need to focus on those things, then again, it’s like Pollyanna, you just have those rose-colored glasses and that’s it. For women or people of color, we’ve never had that privilege and so this was a time when we got people into the room to have those conversations just basically to help people to understand: this is my reality…

“Until you understand or are presented with the realities, then you’re not really expected to be willing to make these changes. Some people, after addressing these concerns, were not able to make these changes, but a majority of the folks were. That’s why it took several years, but they have truly made a phenomenal transition.” (Listen to the interview and read the full transcript here.)

An independent nonprofit coalition of “more than 100 organizations that support its mission to drive collaborative efforts for policy and practices that create a landscape of breastfeeding support across the United States,” the USBC listened to Dr. Bugg and ROSE. They listened, eventually.

On the third morning of the 2019 USBC conference, I left the stiffing, energetic build-up in the ballroom for a walk outside the Hyatt building where, oddly enough, I was greeted on the sidewalk by a formidable, 18 foot-tall granite statue of a pioneer woman holding an infant to her breast and small child by the hand at her feet. A plaque declared her to be the “Madonna of the Trails.” The 1929 statue marks the first portion of the National Old Trails Road leading to the Santa Fe Trail, and the American dream of colonizing the West. Twelve monuments were erected in each of the states the National Old Trails Road passes, shares the online Bethesda Magazine.

What’s her story now? I wondered. After three days of immersion in cultural equity lens perspectives, every story, symbol, and statue’s skirt seemed lifted high enough to glimpse more of the hidden-in-plain-sight truth about its origins. I snapped a photo of the statue and shared it with the women at my table. Darla Birch and Kirsten Kelley, both from the National WIC Association, kindly studied the photo with me.

Is this statue a symbol of all women, mothers, trail-blazing through uncharted territory, like the women in this conference room? Or is this a white woman who is going along with the white dominator narrative to colonize a Native American occupied land while breeding more dominators? What is her story now? Birch and Kelly studied the iPhone photo, shook their heads and decided the she was both.

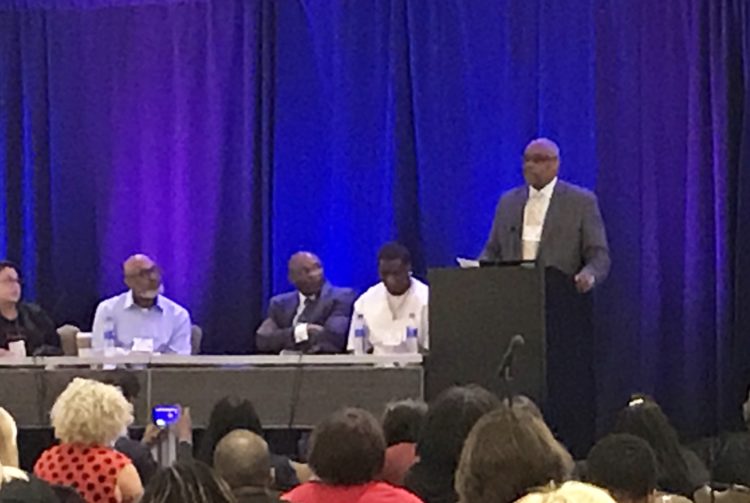

During the last moments of the conference, still considering the implications of concretized, conflicting cultural narratives, I looked up from my laptop to find the ballroom stage filled with black men: black men advocating for breastfeeding. One of the men from Reaching Our Brothers Everywhere, ROBE, declared:

“My vision for breastfeeding, is a vision for my people. Not all black people are struggling. And that has to be said because there are inane, ridiculous statistics out there like, ‘there are more black men in prison than on college campuses.’ Give me a break. But too many of my brothers and sisters are hurting each other, themselves, their families and their communities because THEY are so hurt, confused, distressed. Dissected and disconnected from their history and their own self-worth.

“In my dream, my breastfeeding dream, I see rivers of breastmilk flowing down the streets of these distressed communities. Healing, bonding, nursing and making whole what was dissected and dismembered. My vision for men is that they benefit from supporting and protecting the breastfeeding experience in ways that help them to reclaim their humanity. My vision for ROBE, is that neighborhoods, communities, cities across this country take advantage of and benefit from this assemblage, this collection, in ways that matter to those communities.”

In 22 years of breastfeeding activism, I had not seen or imagined this moment. My knees gave out, my body’s cue that it was impressed and needed to go into deep-listening mode, and I sat down, still applauding with the audience.

These guys are listeners. Their language, presence and love for humanity roiled the room. The last group of presenters yielded their time to ROBE’s Wisdom Council members. Everyone needed to hear more and acknowledge this final arrival at our destination: someone knew how to listen to needs and had a plan to meet them.

In the lobby after their presentation, I met the ROBE Wisdom Council team and asked for an opportunity to bring their stories to Kindred. Kevin Sherman shook my hand and pointed to Wesley Bugg, “He’s our media guy.”

We agreed to talk soon without realizing we would run into each other again, and soon, at the University of California at Hasting’s Center for Worklife Law’s Breastfeeding Policy Summit in San Francisco. At this small summit of invited attendees, we would hear from Joan C. Williams, author of White Working Class:Overcoming Class Cluelessness and the most read article ever on Harvard Business Review, “What So Many People Don’t Get About the US Working Class.” Williams and her worklife law center summit would teach us about another largely unacknowledged -ism that stood in the way of normalizing breastfeeding in America: classism.

At this summit, two months after the USBC conference, I would witness another powerful moment of collective humanity interrupting a well-laid agenda with demands for being heard, the transformation of a Southern lobbyist’s worldview in this moment, and learn the social science language needed to appeal to power-wielding partisan legislators… all while Corporate Goddess statues loomed outside of our 25th floor view of San Francisco’s financial district, daring the world to discover the hidden truth beneath their draped, ethereal forms.

![]()

Mid-Atlantic Regional Break-Out Session

Conference materials ![]()

Close-up of labyrinth

A group shot of the USBC conference attendees, by the USBC. ![]()

Calvin Williams of ROBE

The Madonna of the Trail ![]()

ROBE Wisdom Council members presenting at conference

Class Cluelessness, Corporate Goddesses, and White Supremacy Barriers to Breastfeeding

In July 2019, I left for a long vacation with my family to California, with plans to say goodbye to them in Dillion Beach in August, where a friend would then carry me to the Center for Worklife Law’s Breastfeeding Policy Summit in San Francisco. Traveling three hours to the USBC conference in Maryland was a test of my own deep-listening skills, but traveling with my family across country was a test of theirs. We were good at this by now as, years earlier, my son and I cared for my husband through cancer and, after my subsequent diagnosis, they became attuned to my needs to pace myself while managing AI language (symptoms). With forced practice over time, we are now proficient at moving as a well-attuned pack.

While both bi-coastal events’ goals were normalizing breastfeeding in America, their tone and scope contrasted starkly. In a USBC break-out session, worklife law experts shared stories of human reproduction rights violations in the workplace, including “mooing outside of lactation rooms,” and a statistic that is giving pause to employers: a 600% increase in lawsuits against employers for workplace violations. The Center for Worklife Law’s laser-beam focus on workplace discrimination, legislative advocacy, partisan messaging and “Playing by the Rules” guidelines for lobbying as a nonprofit, felt like an Advanced Activists Only agenda.

Jessica Lee, JD, a presenter at the USBC conference and attorney with the Center for Worklife Law, co-authored the center’s report Exposed: Discrimination Against Breastfeeding Workers, in 2018. The report analyzes breastfeeding legal cases from the last decade to document patterns of discrimination and new data on the scope of existing state and federal laws to protect against workplace discrimination.

The center found that 27.6 million women of childbearing age don’t have the basic protections needed by all breastfeeding workers.

In a Kindred interview, Joan C. Williams, the center’s founder and iconic women’s rights author, blames the lack of workplace support on a more insidious cultural -ism: classism, whose roots in Toxic Masculinity are the real barrier to workplace change.

“We tend to associate work-family conflict with women because they are kind of on the front lines, but it really goes back to how we define the ideal worker and in far too many workplaces today, we still define the ideal worker as someone who takes no time off for childbirth, no time off for family caregiving and no time for breastfeeding. Who does that describe? You know, it certainly does not describe most women. It describes someone with a man’s body and men’s traditional life patterns and even one of the things that we’ve seen over the past since I’ve been working on this issue for nearly 40 years,” said Williams.

“One of the things that’s really dramatic is that there’s been a shift among younger men in what they see as being a good father. Men in my generation, I’m in my 60s, thought that they were great fathers because they changed a diaper. But younger men really are kind of where my generation of mothers were, many of them. They see being a good parent is involving daily care of children and they’re willing to take some career hits to accomplish that, but there’s another group of men, many of them older, some of them equally young, who just don’t see that as being a good father, they see that as being an ineffective breadwinner and an ineffective man.

“So, this is really a conflict among men in the workplace, by people who have defined their lives by being that ideal worker. They see that as the only way to be a real man and an effective person. They are really what is blocking change.” (Listen to and read Kindred’s interview with Williams here.)

The center’s social science research findings and recommendations, well founded and presented, seemed to push the birthright of humanity – to have our needs met, to become the healthy, connected, peaceful species we were meant to be – into a madhouse of smoke and mirrors. Say these magic words to this legislator in the South to get him or her to listen to you, but say these if you’re in the West or talking with Democrats. This was grown up stuff, I admit, and that Williams and her team could enter this realm, stay sane, and report back helpful insights deemed them modern shamans of sorts, I figured.

Why don’t humans see themselves as biological beings and create public policy to serve life? Our life? Our children’s lives? Why do we not use models like the Social Wealth Index to help us understand real wealth? Why don’t we see ourselves as one family, in one world, as Kindred’s slogan pronounces?

This is Kindred’s own nonprofit mission, to provide a safe space for thought-leaders, researchers, professionals and parents, anyone, to question our atypical species’ ongoing degradation of our environment and find ways to bring to life the Evolved Nest, our human birthright coded in our living DNA.

“Children expect the Evolved Nest, provided by their community, and without it become dysregulated physiologically, psychologically, socially, mentally and spiritually,” says award-winning, developmental psychologist and researcher, Darcia Narvaez. “Too much of child treatment today has to do with minimizing babies’ needs, coercing children into shadows of their true selves, leading to societies filled with stress reactive people focused on self-protectionism instead of openness, with limited communal imaginations who are caught up in addictions of various kinds, including work. All these keep us from the social joy and wellbeing our ancestors experienced.”

As Laurel Wilson shared in her TED Talk last year, human milk is the food that evolved humanity.

I considered the summit’s handouts and looked out of the city-scape window where Muriel Castanis’oxymoronically-named “Corporate Goddesses” echoed ancient and modern Western dominator mythology by profanely marrying toxic masculinity and the sacred feminine, and held court over San Francisco’s financial district.

“We need to have a check-in with the women of color in the room to see if they are feeling safe,” said a voice from the opposite end of the small, packed conference room. And just like that, the living energy of humanity entered, with each woman sharing what was alive in her at that moment, what living wisdom needed to be heard, some through tears, some through anger. I listened to the check-ins as deeply as I could, but noticed, within my own being, I did not feel unsafe. My body did not contain a somatic experience of being Black in America. My heart sank and I cried.

What happened? I asked summit coordinator, Jessica Lee, months later. “The USBC conference was joyful and felt like we were all in it in a level that I had not felt before. People seemed to recognize the harms they had done and the new direction that was needed,” she shared in a phone call.

“Going into the summit I felt like we were all there. I entered into the room thinking that we were in a safe space but realized that we all might not feel safe and not be of one mind. How can we lift each other up, feeling that was deeply unsettling? Coming out of it, I realized that the folks who needed to hear the message, heard it very deeply. That moment had a great impact on some of the participants and the organizations they lead.”

One of the participants impacted by this deep-listening moment began recounting her experience in a phone call before pausing and saying, “I can’t tell you the truth of how this affected me without risking my career as a lobbyist in the South. People here don’t understand what I’m doing, advocating for black and poor communities impacted by their legislative processes. They think I’m playing the white power game, and I am.”

She agreed to tell her story, anonymously, and as she did, the interrupted call for safety at the summit revealed a deeper, darker dimension. “I walked away from the summit reflecting upon my role in lobbying and how my success is based on how I have connections to whiteness, white supremacy and white power structures.

“I realized that I was giving myself a pat on the back for being a white savior without including the voices of people impacted by the legislation passed. When I returned to my state, we did change the organization’s mission to include a statement of solidarity, but some people left, and some people said, ‘That’s cute, but what does it really mean?”

I asked her if she had a plan for moving forward in her new state of conflicted awareness? “The answer is to keep doing it, but instead of cherry-picking legislation with a bunch of lawyers, to make sure I am building community, to meet needs, to make sure their voices are truly heard, while also keeping them from harm. It is my proximity to power that allows for the legislation to be considered. We need to have a bigger, internal conversation as an organization. We need to help our board and members.

“We will now be shifting with more intention and insuring everything that we do has intention and is more informed by community and examining how decisions are made and how much power we are allowing communities to have to push us in a direction they want to go. Understanding the class dynamics is also really important, because there are people who cannot read, barely make it to the poverty line in our state. They need to be heard as well.

“The summit helped me walk away with more clarity. I previously felt like I got it, but now I’m sitting in more of a place of learning and listening and pushing myself to do the work and do better. It wouldn’t have happened if not for that moment in the room, the call for a safety check, and listening. It was powerful.”

I left San Francisco with a growing list of questions for the Wisdom Council of Reaching Our Brothers Everywhere. Six months later, in a Zoom call in preparation for Kindred’s series on ROBE, I asked Wesley Bugg, and his mother, Kimarie Bugg, who were at the summit, what happened? We agreed that to us, the pausing of the well-oiled agenda to welcome the living energy of human needs was remarkable.

“I definitely think that it was wonderful,” said Kimarie Bugg in Kindred’s interview this spring. “What happened was, it was time to move on when we were talking about some things that were really felt deeply, particularly they were felt by women of color. But then again, as you mentioned, someone in the room said, “But we’re not really feeling easy and good with where we are with this last agenda item.” So, it felt good to be able to jump out of the ivory tower and to recognize that everybody truly had feelings and concerns and we weren’t going to move on without at least addressing those, or at least letting someone say something.

“There were some tears in the room because some people specifically asked what do you have to say, because they felt that there was some serious emotion in their faces. It was a great time. It was good. It would be fabulous for more meetings to be like that. Again, when people are able to get in touch with how they’re feeling in order to affect policy, that’s going to impact so many other people.

Kimarie Bugg helped to explain my own lack of somatic response, courtesy of my white privilege, to the initial trigger for the safety check-in. “This gets extremely painful for many of us. I’ve held many African American women in my arms who have lost babies to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and grandmothers who’ve lost daughters when they were having babies in childbirth, and that takes a toll on you. It takes a toll to be the mother of a black son in America, just always concerned about, are they going to make it home safe, for many reasons. It really felt good for that organization to allow that space so that everyone could go around and check in just for a few minutes, and everybody needs to do that.”

![]()

The Center for Worklife Law’s group photo of the Breastfeeding Policy Summit attendees. August 2019.

Lisa Reagan of Kinded; Tina Sherman of MomsRIsing; Kinkini Banjeree of USBC; and Cheryl Lebedivitch of USBC ![]()

Lisa Reagan, Kindred; and Kimberly Seals Allers ![]()

Conference agenda and Corporate Goddesses

Re-entry, Recaps, and Rants

As she promised, on my return to Virginia, Laurel Wilson, USBC’s former board member who witnessed firsthand the organization’s ongoing evolution from a white professional power structure to a more consciously inclusive coalition, and who is also a Kindred International Advisory Board member, emailed her thoughts:

“My board work on the USBC was possibly the most exciting, challenging, and rewarding service I have had the opportunity to be involved with in my 27 plus year career. As I started my service, the organization was making an intentional shift to not only embrace the ideals of equity, inclusivity, and diversity but to actually look like the lactation world we all worked in,” Laurel wrote.

“Over my three years, we became an organization that worked diligently to have the board, staff, and membership reflective of breastfeeding/chestfeeding communities in the US. It was refreshing to attend conferences and serve on a board where communities of color and LGBTQIA communities in the parental/child health field were present, heard, and honored. We focused on addressing the difficult issues of racism, implicit and explicit biases, not just in the lactation community but in our organization itself. I feel as though this organizational shift will improve the landscape of lactation.”

While the USBC’s transformation is commendable, it comes at a time when research is revealing nonprofits to be bastions of and vehicles for racism, white privilege and white supremacy. A Chronicle of Philanthropy article states:

“The fact is, we cannot easily or perhaps ever fully outrun this issue unless we embrace a hard truth: Racism and its impact are bright, red throbbing tributaries in America’s body politic.

“It is not a malady that swoops down on our country like a bad cold or an ill wind. It is part of the bones and the architecture of our country and has been since America’s inception.

“Confronting this hard truth and, more important, reducing the effects of racism and inequality require that we at foundations and nonprofits address institutional barriers throughout society. It also requires introspection — from those in leadership positions, especially — to acknowledge and understand the roots and reality of interpersonal intolerance and division.”

Sadly, this year’s USBC conference, along with most conferences, was cancelled due to the coronavirus lockdown. The USBC’s website’s tools for equity, diversity and inclusion education are vast, and a great starting point for their members and the public. With 100 organizations in their network witnessing their progress, it will be interesting to discover if their process is replicable, sustainable, or even welcome in state and local coalitions.

Later this spring, as our nation began to emerge from the shock of COVID-19’s deadly sweep, many thought leaders, like Kimberly Seals Allers, also a presenter at the Center for Worklife Law Summit, began to wonder if our quarantine time could result in rethinking our values? Perhaps the forced pattern interrupt of our unsustainable daily lives could result in attuning our attention to our own needs? Other countries have healthcare, paid leave, maternity and paternity leave, midwifery models of care, that also support breastfeeding goals of families. Why couldn’t American people have these social safety-nets too?

Oh, that’s right, because activists need to tread lightly on the toes of legislators entrenched in white power – while black mothers die in three times greater rates than white mothers – by learning language that will not alienate them, and lobbyists need to learn to function with existential, internal conflict torn between placating white supremacists and serving communities of color impacted by legislation. Meanwhile, American workers are held to a lethal Toxic Masculinity Model that guides them into early graves, while we spend more money on healthcare than any nation on earth and have the worst health outcomes, highest maternal and infant mortality rates, and the next generation wonders, maybe for the first time, what does sustainable living look like? Is it too late?

And don’t get me started on those damned Corporate Goddesses…

Meet the Men of ROBE: Standing at the Intersection of Breastfeeding, Infant Mortality, and Social Justice

On May 20, 2020, Mothers Jones published the article, Breonna Taylor Is One of a Shocking Number of Black People to See Armed Police Barge Into Their Homes, describing how police officers barged into Breonna Taylor’s home on March 13, 2020, in Louisville, Kentucky, in the middle of the night and discharged a spray of bullets that struck and killed the 26-year-old EMT.

Six days later, on May 26, 2020, George Floyd, and unarmed African American man arrested for passing a bad check, was murdered by white police officer, Derek Chauvin, who held his boot on Floyd’s neck after Floyd begged for breath and cried out for his dead mother to help him. The murder of Floyd, while he was handcuffed and face-down on the pavement, captured in a nine minute-long, now viral video, sparked protests for justice, beginning in Minneapolis the day after his death and expanding in over 400 cities throughout all 50 U.S. states and internationally.

There are no words in me for this moment, only the heavy acknowledgement of the song humming ceaselessly under my own rage. It is grief. And perhaps a hope that all activists stepping forward will enter into a deep-listening practice with their own bodies so that we all may go the distance this historic moment will require of us. May we all be blessed with family and friends to hold us up so we can move through this transition together as a well-attuned pack.

In June, one year after meeting ROBE’s Wisdom Council members at the USBC’s national breastfeeding conference, Kindred’s social justice team wrapped up our review of 100 pages of transcripts and six hours of audio interviews with ROBE and Kimarie Bugg, while, thirty miles from my Virginia farm, Confederate statues – a cultural symbol of a permanent deaf ear to human needs – were being dragged through the streets, dumped in lakes, and beheaded in the former capital of the South.

The Frederick Douglass quote at the opening of this post warns, “The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.” Douglass wrote this in a letter to abolitionists in 1848.

Maybe we’ve met our limit as a human family, of what we will endure. Maybe we will start listening now, and make a condition of future leadership good listening skills. David Metler, Kindred’s social justice editor, often quotes Atul Gawande, cultural “change happens at the speed of trust.” How long will it take to build the trust needed for lasting change?

David, and Reshma Grewal, Kindred’s Spirit-in-Resident research student from the University of California at Santa Barbara, sat down with ROBE’s Wisdom Council members this spring with the intention of discovering how their deep-listening, trust-building, safe space-creating, and truth-telling strategies allowed them to train fathers to be advocates for breastfeeding and healthy birth in the African American community. Their personal stories, and how they transformed themselves first, before serving their communities, provides a living model for sustainable social justice reforms and life-affirming cultural change.

Despite current trends, the revolution will not be Tweeted, because this is not who and what we are as a species. We will need to make time to sit in safe circles, in person or virtual, as our ancestors did and we are designed to do as reality-creating storytellers, to begin the deep-listening process that can eventually rewire our neurobiology, ignite our heart wisdom, and help us become the embodied models of peace our children need us to become. Our other option is to emulate the deaf, silent, granite cultural symbols of an Old Story, and allow our apathy, inattentiveness and denial to continue to erode our spirits and planet.

We hope you will make time to listen to ROBE’s stories, and let us know your thoughts of how Kindred can continue to serve you, and the New Story of the Human Family.

You are welcome to join our virtual campfire discussion here.

RESOURCES

Kindred’s Equity-Diversity-Inclusion Resources

Kindred’s Black Mothers and Fathers Resources

The Evolved Nest.The Evolved Nest is a breakthrough concept that integrates findings across fields that bear on child development, child raising and adult behavior. The Evolved Nest promotes optimal health and wellbeing, cooperation, and receptive and sociomoral intelligences. Societal moves away from providing the Evolved Nest have contributed to the ill being and dysregulation we see in one another and society. Learn how to nest your children and re-nest yourself.

Saving Tomorrow Today: An African American Breastfeeding Blueprint. A new report from Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere, ROSE.

Center for Worklife Law. The Center for WorkLife Law is a research and advocacy organization at UC Hastings College of the Law that seeks to advance gender and racial equity in the workplace and in higher education. WorkLife Law focuses on initiatives that can produce concrete social, legal, and institutional change within three to five years.

Our current major initiatives include programs for advancing women leaders, eliminating barriers for pregnant and breastfeeding workers and students, preventing Family Responsibilities Discrimination, and helping companies prevent or interrupt bias in the workplace and create more stable schedules for hourly workers.

United States Breastfeeding Committee.The United States Breastfeeding Committee (USBC) is an independent nonprofit organization that was formed in 1998* in response to the Innocenti Declaration of 1990, of which the United States Agency for International Development was a co-sponsor. Among other recommendations, the Innocenti Declaration calls on every nation to establish a multisectoral national breastfeeding committee comprised of representatives from relevant government departments, non-governmental organizations, and health professional associations to coordinate national breastfeeding initiatives. The USBC is now a coalition of more than 100 organizations that support its mission to drive collaborative efforts for policy and practices that create a landscape of breastfeeding support across the United States.

Center for Nonviolent Communication. See a list of human needs here. Learn deep-listening skills here as well!

Summary of Racial Identity Development. How far are you down your path?

Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture. See how closely related Toxic Masculinity, Patriarchy, Narcissism, and White Supremacy are on this website.

Dismantling Racism. An online workbook.